Anderson Noir Valley

Anderson Valley will never rival its southerly neighbor, the Russian River Valley, for notoriety. Retirees and

urban refugees with money seeking the wine lifestyle won’t fine the creature comforts here. There is no

restaurant scene, spa or high-end lodging. The local inhabitants discourage tourism, calling intruders “wine and-

cheese gentry.” Their worst fear is that this bucolic valley might become a destination wine region. The

locals’ disdain for city people is reflected in the unique language of the Anderson Valley known as boontling,

which refers to visitors as “brightlighters.” Despite this indigenous aversion to outsiders, the pinotphile

cognoscenti have descended on the Anderson Valley, reveling in the magnificent Pinot Noirs that are

threatening to make this slow lane region a wine lover’s paradise. Pinotphiles are a determined group, addicts

if you will, looking for that next fix of Pinot Noir and rarely deterred by a challenge. They will travel anywhere to

find what Adam Lee of Siduri Wines calls “true-believer” wineries that produce Pinot Noir because “it is the true

enological love of their lives.”

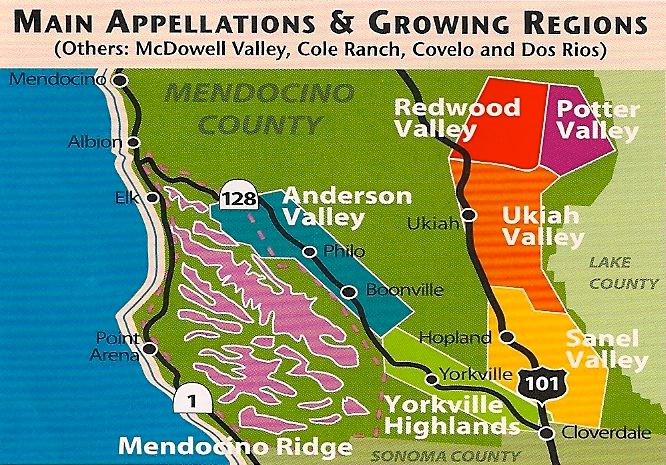

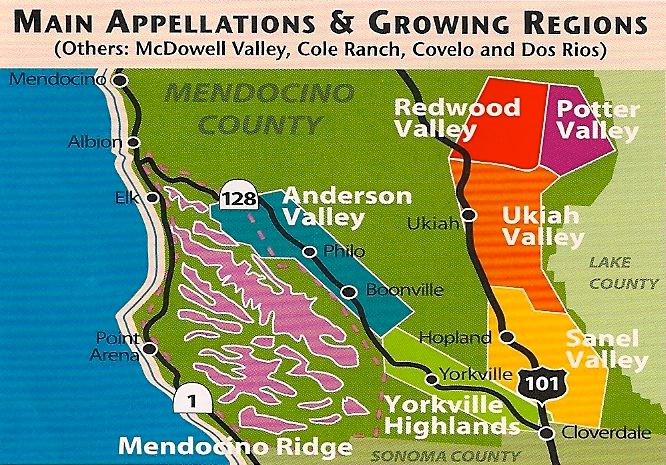

Anderson Valley is one of eleven grape-growing appellations in Mendocino County, California, but is the most

uniquely suited to growing that insolent grape, Pinot Noir. Plantings of Pinot Noir in Mendocino County (2,204

acres) are overshadowed by Chardonnay and Cabernet Sauvignon and rank fifth among the other major Pinot

Noir growing regions of California (Sonoma,10,192 acres, Monterey, 7,123 acres, Santa Barbara, 4,140 acres

and Napa, 2,756 acres). The average price per ton for Mendocino Pinot Noir ranks fourth in the state at $2,486, trailing Sonoma ($3,168), Santa Barbara ($3,106), and Napa ($2,588), and exceeding Monterey

($1,842). Exceptional Anderson Valley Pinot Noir vineyards can command up to $6,000 per ton.

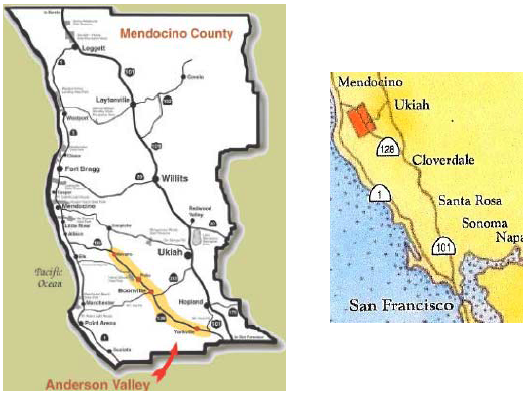

Anderson Valley is located between mile marker 9 and 50 on Highway 128, 120 miles north of San Francisco.

It is a relatively isolated area mostly less than a mile across with 1,000+ foot mountains on both sides. The

valley floor is about 18 miles long and opens on its northern end to the Pacific coast by way of the Navarro

River Canyon. At this most northerly portion of the Anderson Valley, the Pacific Ocean is but a 15 mile twisting

drive away. The resulting marine influence allows morning fog to roll into the valley and gentle breezes to enter

in the afternoon. A gradient is created, with the northern end, referred to by locals as “down-valley,” or the

“deep end,” receiving more rain and fog and thus being cooler, and the southern more inland portion, or “upper valley,”

being typically 8-10 degrees warmer. The valley’s vineyards and wineries are clustered along the

fringes and rolling hills adjacent Highway 128, which bisects the valley in a south to north direction, with a

majority of the vineyards located down-valley. Along Highway 128, the vineyards begin at the town of

Boonville, continue north through Philo, and end in the tiniest hamlet of the three, Navarro, population 67.

Most visitors access the Anderson Valley by way of Highway 128 as it departs westward from Highway 101 at

Cloverdale, 80 miles north of San Francisco (Confusingly, Highway 128 east is approached first heading north

and takes you to Guerneville). Once on Highway 128 west, the traveler enters a pastoral land of great beauty,

the pulse slowing with each mile traversed, assuming you don’t meet with any timber trucks barreling south on the narrow two-lane highway. The world of roadside McDonalds and gas stops is left behind, replaced by a

countryside laced with lichen-covered oaks, towering redwoods, ramshackle old barns, and calmly grazing

sheep and cows. The smell of skunks and hay fills the air. In 30 minutes, Yorkville appears, the town center of

the Yorkville Highlands AVA. There are 22 vineyards here planted to 21 different wine grape varietals primarily

at higher elevations between 1,000 and 2,200 feet. Cabernet Sauvignon is most suitable for this warm region

where the vineyards, all family run, average 18 acres each. There are a few microclimates suitable for Pinot

Noir in Yorkville Highlands, notably the Weir Vineyard at mile marker 43.3 farmed by owners Bill and Suki Weir.

About 50 acres of Pinot Noir total are planted in the Yorkville Highlands. After leaving Yorkville and another 15

minutes of driving, the township of Boonville appears, the so-called “center of activity” in the valley. About

3,000 people are scattered throughout the Anderson Valley, a fourth of them calling Boonville home.

Boonville is known as “Boont” in the unique local language of Anderson Valley known as boontling. In the

1800s, this code-like dialect become the spoken word for many of the valley residents. The exact origins are

unclear, but many attribute the derivation to the mothers and children who worked in the hop fields that were

prevalent in the valley at the time. The isolation of the valley and the distrust of visitors fostered the language.

Terms included: “Boont Region” (Anderson Valley) “baul seep” (lovers of wine), “baul hornin” (good drinking),

“Frati” (wine - Mr. Frati was a local vineyard owner), “Frati shams” (wine grapes), “backdated chuck” (someone

who is behind the times) and "Boontners" (speakers of Boontling). Many of the words were derived from other

languages including Scottish, Irish, Spanish and the dialect of the Pomo Indians who were the original Native

American settlers of the Anderson Valley. Today, fragments of boontling persist as slang terms.

Among the first white settlers in the Anderson Valley were the Anderson family who arrived in 1851. Walter

Anderson planted the first apple trees in the valley and this became an agricultural staple. Hop fields became

ubiquitous and a thriving sheep and timber industry developed. The 1960s brought an influx of hippies who

were drawn to the beauty and isolation of the valley. They fostered an illicit marijuana enterprise which to this

day remains the biggest grossing agricultural product in the valley, exceeding wine grape growing. During the

1970s and 1980s, urban escapees, so-called “back-to-the-landers,” bought ranches and replaced apple

orchards with vineyards. This movement continues at a slow pace to this day. The latest newcomers to the

valley are Mexican laborers valued for their work in the vineyards. Olives are the newest crop and several olive

oil producers including well-regarded Stella Cadente have appeared.

The history of winegrowing in Mendocino County is linked most closely with Parducci (the oldest modern

winery in the region dating to 1931) and Fetzer (dating to the late 1960s), both of whom flooded the market

through the years with wines of reliable value from the warmer areas of Mendocino County outside the bounds

of the Anderson Valley. The history of viticulture in the Anderson Valley goes back to the Italian immigrants who

arrived from San Francisco and successfully raised grapes above the valley along the Greenwood Ridge in

what is know the Mendocino Ridge AVA. The immigrants favored Zinfandel, Muscat, Malvasia and Palomino.

The DuPratt Vineyard, planted in 1916 on Mendocino Ridge is still viable. In the 1940s and 1950s, attempts to

grow grapes in the valley by Asti, Goodhue and Pinoli were largely unsuccessful due to problems with ripeness

and frost. The modern history of winegrowing in the Anderson Valley is linked to four names: Edmeades,

Husch, Lazy Creek and Navarro.

In 1963, Dr. Donald Edmeades, a cardiologist from Pasadena, California, bought the Nunn Ranch, consisting

of 108 acres of grazing and orchard land north of Philo. He planted 24 acres of grapes excluding Pinot Noir in

the late 1960s. The locals were quite skeptical and Edmeades, in good humor, put up a sign on Highway 128

that read, “Edmeades’ Folly.” In truth Edmeades had carefully researched the potential for grape growing in

the Anderson Valley and had been visiting the region on vacations since the 1950s. The University of

California Davis viticulturists had completed a survey of the climate of the valley at the time and classified it

primarily as Region I (up to 2,500 degree days), ideal for cool-climate grapes. Edmeades was successful

growing Chardonnay and Gewürztraminer, and supplied Parducci and Seghesio for nearly ten years. In 1972,

the Edmeades winery and label was launched but both Donald and his wife passed away from cancer just after

his winery was built. His son Deron took over and crafted the first vintage. Edmeades, which was acquired by

Kendall-Jackson in 1988, achieved notoriety with Zinfandel but was never a major player in the Pinot Noir

game in the valley.

The first Pinot Noir planted in the Anderson Valley was at Husch Vineyards in 1968. Founder Wilton (Tony)

Husch had been exposed to Pinot Noir by John Parducci and after acquiring the 60-acre Nunn Ranch halfway

between Philo and Navarro, selected a 3-acre parcel of the Husch estate known as the Knoll block. According

to John Haeger (North American Pinot Noir, p 309), the original plantings were taken from Wente’s Arroyo Seco

vineyard. In 1971 the first crop was harvested, and the back room of the Nunn Ranch house, built in 1920,

became the first modern winery in the valley. Long time vineyard manager, Al White, arrived in 1973. As Al

recounts his first harvest at Husch in 1974, clearly vineyard management was archaic at the time.

The vines were planted with 8’ by 12’ spacing with overhead irrigation. Trellising was minimal and no leaf

pulling was done. Rain at harvest was a problem and with it came mold for which there was little suitable

treatment. The grapes were picked to apple boxes at a very casual pace over several days by a hippie crew.

The Knoll block is still producing Pinot Noir, but was inter planted with Dijon 667 clone in 2001 and transformed

by modern viticultural practices. Tony Husch sold the property in 1979 and there have been a string of

winemakers and owners since then.

The third noteworthy modern winegrowing pioneer in the Anderson

Valley was a restaurateur from San Francisco, Johann Kobler and

his wife Theresia. They bought the 20-acre Lazy Creek Vineyards

in 1969 from the Pinoli family who started their farm in Philo in the

early 1900s. According to the Anderson Valley Historical Society,

Joe Pinoli had the first bonded winery in the valley in 1911 and

planted the first vineyards on the valley floor. The Pinolis had

more success with fruit orchards than vineyards. Kobler was able

to revitalize the vineyards and built a small winery in 1973. He

had success with both Pinot Noir and Gewürztraminer. Josh and

Mary Beth Chandler acquired Lazy Creek Vineyards in 1999 and

carried on the tradition admirably until 2008 when they sold the

estate to Ferrari-Carano. Ferrari-Carano continues to manage

Lazy Creek Vineyards as a separate winery and label.

Ted Bennett was a successful businessperson when he and his wife, Deborah Cahn, left San Francisco in

1973 and bought a 900-acre sheep ranch along Highway 128 between Philo and Navarro. They were Alsatian

grape aficionados and initially only planted white varieties beginning with their first plantings in 1974. Pinot Noir

came later and today they have 31 acres of estate Pinot Noir and source additional Pinot Noir from other

Anderson Valley vineyards. Their marketing prowess was largely responsible for Anderson Valley’s recognition

among wine enthusiasts. They built a welcoming tasting room and regularly sent out an informative newsletter

that led to considerable consumer-direct sales. The second generation, Aaron and Sarah Cahn Bennett, are

actively involved in the winery today. The long time gray-bearded winemaker is Ted Klein, who can easily be

confused in appearance with owner Ted Bennett. Today, their lineup of quality wines is impressive and includes

Gewürztraminer, Riesling, Sauvignon Blanc, Pinot Gris, Muscat, Syrah, Zinfandel and Pinot Noir (three

bottlings including Anderson Valley, Méthode a l’Ancienne and Deep End Blend). Navarro Vineyards & Winery

has broken ground recently on a second winery located in Boonville and are adding new plantings nearby.

Although the Edmeades, Husch, Lazy Creek and Navarro wineries laid the groundwork for success, Anderson

Valley’s validation as a premium grape-growing area was firmly established by two sparkling wine producers,

Roederer Estate in the early 1980s and subsequently Schraffenberger. Still, the public’s perception of

Anderson Valley wines has lagged primarily due to the small number of wineries, the sale of large amounts of

grapes to wineries located in Napa and Sonoma with more visible profiles, and the anti-tourism and

anti development attitude that is prevalent among the residents of the valley. The paucity of lodging and

creature comforts have prevented the Anderson Valley from becoming a wine destination and many visitors to

the valley simply pass through on their way to the Mendocino Coast, stopping only at a few visible winery

tasting rooms on Highway 128.

Some have compared the Anderson Valley to Oregon’s Willamette Valley which is similarly largely rural and not

overwrought by tourism. Both climates fall into the coolest Region I, with Oregon being cooler at 1,924 Celsius

degree-days compared to Anderson Valley at 1,900 to 2,300 Celsius degree-days (Burgundy is at 1,982

Celsius degree-days). Rainfall is almost identical in the two regions, averaging about 40 inches annually. In

addition, Anderson Valley wines bear more resemblance to those from the Willamette Valley than to other

California appellations, and as a result, the Anderson Valley has been dubbed “Baja Oregon.” The structural

elements, that is the tannins and acidity of Pinot Noir from the Anderson and Willamette Valley, are closely

aligned with Burgundy. What distinguishes Anderson Valley from Oregon is the heavily marine-influenced

climate. The Willamette Valley is largely protected from the Pacific coast by its Coastal Range of mountains,

but the proximity to the Pacific Ocean at Anderson Valley’s deep end leads to the frequent intrusion of

afternoon ocean breezes and evening fog, resulting in a temperature moderating effect most prominent in the

summer. As the sun goes down, warm days give way rapidly to very cool evenings resulting in marked diurnal

variation (a midday temperature of 82 degrees might give way to a nighttime temperature of 45 degrees). This

allows the grapes to accumulate acidity and retain it. The downside is that nighttime cold snaps can create

frost damage to vines. The 2008 vintage year was marked by the worst series of frosts in April since the early

1970s. Flower damage on primary buds from last year are shown below right compared to a healthy vine from

Handley Cellars this May.

While both Oregon and the Anderson Valley began plantings of Pinot Noir about the same time in the mid

1960s, Oregon’s quicker accent to success can be largely attributable to the clones that were planted. While

Oregon was committed initially to Pommard and Wädenswil clones, both of which turned out to be quite

appropriate for the Willamette Valley climate, Oregon had the advantage of earlier and widespread plantings of

the cool-climate Dijon clones. Anderson Valley was primarily planted to California heritage and sparkling wine

clones initially. The Dijon clones, which are earlier ripening and often more suitable to the climate in Anderson

Valley, came later. The Anderson Valley has had to catch up, but today as newer plantings of Dijon clones are

reaching significant maturity, the Pinot Noirs are fulfilling the promise of “baul hornin’”

Besides Pinot Noir, the Anderson Valley is perfectly suited for Alsatian varieties such as Pinot Gris, Riesling

and Gewürztraminer. Each year the Anderson Valley hosts an International Alsace Varietals Festival in

February. Chardonnay can also shine in the Anderson Valley and is an important component of the region’s

sparklers.

Mendocino Ridge

Mendocino Ridge is a newer American Viticultural Area winning approval in 1997, yet has

some of the oldest producing vineyards in Mendocino County. The first plantings, primarily

Zinfandel, were established by Italian immigrants and date to the late 1800s. Today, Zinfandel

is still the pride of this AVA, but the area holds promise as California's newest “hot spot” for

Pinot Noir.

The Mendocino Ridge AVA is a non contiguous trio of ridges that is defined by vineyards at

least 1,200 feet or more in elevation and within 10 miles of the Pacific Ocean. It is California's

first and only non contiguous AVA. Because of the hilly terrain of the AVA some lower elevations

are not included, fostering the name, “Islands in the Sky™.” This catchy name is trademarked by

Dan Dooling, owner of Mariah Vineyards, and one of the winegrowers along with Steve Alden

of Perli Vineyard to successfully achieve appellation status for the region. The ridge is a

twisting 12 mile uphill westward drive along Philo Greenwood Road from the Anderson Valley floor.

Refer to map on page 2.

The climate is different from the Anderson Valley below. Perched above the fog and frost

threat, the vineyards bask in the early morning sun, and early afternoon breezes cool down the

fruit, never allowing the temperatures to rise as high as the valley below. The diurnal variation

during the growing season is significantly less than the valley below (20 degrees versus 40

degrees). There is enough rainfall and ground water to dry farm vineyards. According to

winemaker Van Williamson of Edmeades, “Mendocino Ridge grapes produce wines intense in

fruit, high in acidity and structured for aging in the cellar.”

The first winery in the AVA was Greenwood Ridge Vineyards in 1980 (their tasting room is in

the Anderson Valley below). The original Greenwood Ridge Vineyard was planted by Tony

Husch in 1972 and was acquired in 1973 by Greenwood Ridge owner Allen Green. Listen to Allen Green speak about Mendocino Ridge: [audio.60 |“Allen Green at AV Technical Symposium”]]

Other Pinot Noir plantings include Manchester Ridge Vineyard (19 acres of Pinot Noir and 11 acres

of Chardonnay), Perli Vineyard (6.5 acres of Pinot Noir) and Sky High Vineyard. Other

wineries producing Pinot Noir in the Mendocino Ridge appellation include Baxter Winery,

Drew, and Phillips Hill Estates. Wineries sourcing fruit from the Mendocino Ridge AVA include

Arista (Perli Vineyard), Ferrari-Carano (owners of Sky High Vineyard) and Auteur, B. Kosugi, J.

Jacamon, Marguerite Ryan Cellars, Tandem (all Manchester Ridge Vineyard).

I have had spectacular Pinot Noirs from Manchester Ridge Vineyard. Greg La Follette, former

winemaker at Flowers, commented on the first Pinot Noir harvested from Manchester Ridge in

2005 and said, “....this vineyard is bound to be another Flowers Camp Meeting Ridge - even

better.” The vineyard is pictured below from the Manchester Ridge Vineyard website at

www.manchesterridge.com.

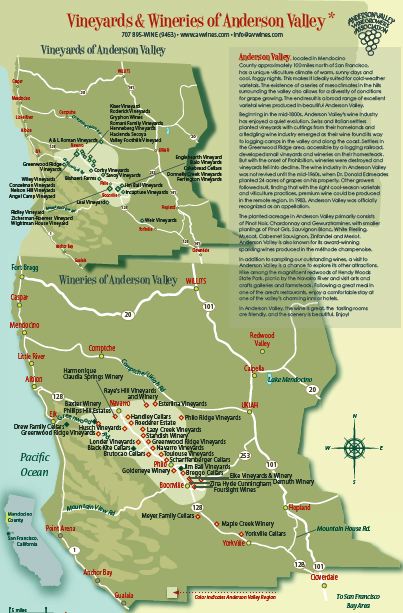

Currently there are 28 wineries and more than 60 vineyards in the Anderson Valley. Some of the vineyard

names have become household words to pinotphiles: Cerise, Demuth, Donnelly Creek, Ferrington, Klindt,

Morning Dew Ranch, Savoy, Toulouse and Wiley. For a full listing of Anderson Valley wineries and vineyards

and an extensive map (see below) consult the Anderson Valley Winegrowers Association website at

www.avwines.com.

Over 30 major California Pinot Noir producers outside the Anderson Valley appellation access grapes from

Anderson Valley: Anthill Farms, Arista Winery, Adrian Fog, Barnett, Benovia, Brogan Cellars, Cakebread

Cellars, Copain Wines, Couloir Wines, Chronicle Wines, Dain Wines, Drew, Fulcrum Wines, Hartford Family

Wines, Harrington, Ici/La-Bas, La Crema Winery, Littorai, MacPhail Family Wines, Madrigal Vineyards,

Papapietro-Perry, Radio-Coteau, Roessler Cellars, Saintsbury, Skewis, Tudor, Twomey, Waits-Mast Family

Cellars, Whitcraft, Williams-Selyem and Woodenhead.

Most of the vineyards in the Anderson Valley are less than 10 acres, with three large growers, Roederer Estate,

Goldeneye and Navarro controlling the most total vineyard acreage. Pinot Noir acreage has dramatically

increased since 1997, and now accounts for more than 50 percent of Anderson Valley’s vineyard plantings.