Balance in Wine: A Personal Aesthetic

Balance is an abstract term that is offered as a high accolade whenever quality of wine is analyzed. It

represents a subjective harmony between all of wine’s components that produce flavors and haptic

characteristics (sensations appreciated by the palate) of taste, including acid, sugar, alcohol, tannin, fruit

extract, oak, and texture, with no one element dominant. With over 300 chemical constituents in wine, it is

impossible to analytically arrive at a determination of balance. We are left with our personal taste to ascertain

balance and therefore quality in a wine. Balance is a personal aesthetic that is hard to describe, almost like

explaining sex to a virgin, but we know it when we experience it.

Definitions of balance abound and here are a few examples:

Karen McNeil, The Wine Bible: “A wine that incorporates all of its main components - tannins, acid and

alcohol - in a manner where no single component stands out.”

eRobertParker: “One of the most desired traits in a wine is good balance, where the concentration

of fruit, level of tannins, and acid are in total harmony.”

Emile Peynaud, The Taste of Wine: “A wine is said to be harmonious when its elements form a pleasing

and well proportioned whole. In a good wine, everything should be harmonious; quality is always linked

to a subtle play of balances between tastes and smells.”

Winemaker Jim Clendenen of Au Bon Climat (at this year’s WOPN): “Balance is a person that wakes up

in the morning and does the New York Times crossword puzzle. They are motivated, educated and

want a challenge. That’s balance. Then there’s the intellectually lazy, uneducated unmotivated person

who does the USA Today crossword puzzle.”

Jeffrey Patterson, proprietor and winemaker at Mount Eden: “A balanced wine is one in which the last

glass tastes better than the first.”

Ted Elliott, winemaker, T.R. Elliott : “If a wine tastes great, yet you can’t describe it, it’s in balance.”

Some facts about balance which help to further define it:

A number of descriptive terms are employed to describe wines that are not in balance. Hard or harsh or

astringent: too much astringent tannins. Fat or lush: rich and concentrated, blessed with extract; if too

fat, said to be flabby. Thin: lacking fruit. Austere: acidity levels are high compared to fruit and in its

worse form said to be tart. Terms can also be complimentary descriptions of balance. Supple refers to

a harmonious, soft and velvety wine. Crisp or lively describes a pleasing sense of acidity.

Balance in wine is temperature dependent. Tannins are more noticeable and a wine seems more acidic

when the wine is at a low temperature. Alcohol is more apparent at high temperature.

Balance is in the eye of the beholder. We know that individuals differ in their sensitivity to alcohol and

tannins. The taste genes determine how many taste bud receptors a person has for sweetness,

sourness, saltiness and bitterness. Hyper-tasters do not enjoy strong tannins and high alcohol.

Regular tasters (at 75%, the majority of the population) find sugar more palatable, high alcohol less

bitter, and tannins less repulsive. Non-tasters are more forgiving of strong tannins and alcohol.

Balance in wine is a delicate interplay. An increase of one element can obscure the perception of

another element, For example, tannins are more pleasing if acidity is low and alcohol is high. Acidity is

perceived as well integrated when the alcohol percentage is higher.

Balance is an indicator of age ability. Acidity and balance are the key factors that determine the aging

capability of a wine.

Balance is often tied to alcohol in the public’s perception. Many believe a wine with high alcohol, say

above 15%, cannot be balanced. Allen Meadows, aka Burghound, has said, “I flatly disagree that a

15% alcohol wine can be balanced.” Others would disagree, and this has become a contentious issue.

Low alcohol is no guarantee of balance, and wines with an alcohol percentage of, say, 13.5%, can be

unbalanced.

Can an unbalanced wine assume balance over time in the bottle? I have heard the comment bantered

about by a number of knowledgeable wine people, “If a wine is not balanced when it is put in the

bottle, it will never be.” There is disagreement over this and the remarks of winemakers to follow

provide insight on this issue.

Balance and style in wine are intertwined and the style of the wine will often dictate the possibility of

balance.

The goal of Pinot Noir winemakers today is to achieve balance in wine naturally, without alcohol reduction

strategies or acid modifications. This topic has been the subject of seminars at the recent World of Pinot Noir

(“Alcohol and Balance”) and in San Francisco (“California Pinot Noir: In Pursuit of Balance”). At the San

Francisco event, attended by members of the trade and press, the moderator, Ray Isle, offered the question,

“Does Pinot Noir require more balance than other varieties?” A corollary of this is the question, “Is it more

difficult to achieve balance in a Pinot Noir wine?” These are interesting questions and the answer to both is

probably “yes,” but the winemakers and sommeliers in attendance never really answered the question.

One thread that ran through both seminars was the critical relationship between wine balance and vine

balance. There is general and emphatic agreement that Pinot Noir vine balance results in better fruit quality,

and increases the potential harmony of the finished wine. Dr. Andy Reynolds, a viticulturist at Brock University

in Ontario, Canada, remarked (American J Enol Vitic, 56:4, 2005), “There is a general acceptance that high

quality wines are produced from vineyards where balance is maintained between yield and vegetative growth.”

This is a critical idea that I will briefly explore.

Vine balance can be achieved through viticulture practices and can be measured by both qualitative and

quantitative criteria. Qualitative criteria are defined by the appearance of the vine, including its vigor and leaf

color. Patty Skinkis, of Oregon State University (www.extension.org/pages/33109/basic-concept-of-vinebalance)

provides a summary of how vine balance can be quantified. “Vine balance is the state at which

vegetative and reproductive growth lead to the most ‘balanced’ vine. Vine balance is measured by vine growth

and capacity through fruit yields and vine size and can be defined and characterized as the ratio between vine

yield and vine size (representing reproductive and vegetative production of the vine, respectively). This

relationship is known as crop load and is calculated by taking the vine’s yield and dividing by the dormant

pruning weight. A vine is considered in balance within the range of 5-10:1 for vinifera. A low ratio (low yield,

large vine) means the vine is under cropped and a high ratio (more fruit, smaller vine) signifies the vine is

over cropped.” Other quantitative measures used to understand vine balance include cane pruning weight

alone (a weight of 20-30g/cane is considered balanced), vine leaf area, cane diameter, and inter nodal length.

Achieving ideal vine balance is challenging and influenced by many factors including climate, soil, rootstock

and scion, canopy management, trellising, water availability, disease and pests. It may take a grower

generations to fully understand the complex interplay of these many factors, a realization voiced by

experienced grower, David Hirsch, of Hirsch Vineyards in the Sonoma Coast at the recent San Francisco

seminar on balance.

With this information as background, who better to ask about wine balance than winemakers? I approached

several noted Pinot Noir winemakers and asked them three questions: (1) What is your definition of wine

balance? (2) How do you determined balance in a wine? (3) Can wine be naturally balanced, and if it is not,

what role can vinification play in achieving wine balance? I also posed three questions to some of my readers:

(1) How do they define balance? (2) How do they determine if a wine is balanced? (3) Is balance important in

their choice of Pinot Noir to drink?

Michael Cox, Winemaker, Schug Winery, Carneros, California. (1) “My definition of balance is tied to

acidity/fruit/tannic structure. For me, these are the three key components of a wine. If the balance is tipped

too much in one or more directions, the wine is less than it could be. Overtly fruity wines are nice, at first, but

without acidity and tannins to act as counterweights, they just simply fall a bit short.” (2) “The only way to

determine if a wine is balanced is to taste. We all have our own ‘sweet spot’ of balance and that varies with

wine type to a degree. In blend decisions at Schug, we tend to focus on the balance aspect. My own view is

that if the wines tastes right, the aromas will follow.” (3) “Wine should be naturally balanced, though sometimes

a winemaker can lose sight of that during harvest in pursuit of an artificial number. That is where skill and

craftsmanship in winemaking comes through. Knowing your vineyard and when that fruit is ready, allows you

to make a balanced wine. That requires tasting in the vineyard and hard-earned experience. That doesn’t

mean that winemakers should not intervene if a wine seems out of balance. There are decisions (acidification,

fermentation regimes, oak programs, aging regimes, etc.) that can be made to bring a wine back into balance.”

Eva Dehlinger, Winemaker, Dehlinger Winery, Russian River Valley, California. (1) “It is useful to think

about balance as an overarching principle rather than as a strict definition. A balanced wine is simply one that

has harmony between various structural elements. For example, a wine where the most important factors

complement each other well. An unbalanced wine may have one or more components that are noticeably

unwieldy considering the profile of the wine. For example, this could be too much or too little acid, alcohol,

tannins, sugar or oak. Such imbalance is distracting and detracts from one’s overall satisfaction of a wine.

Happily, there are many profiles of balanced wines, and this affords us diversity in vinous enjoyment. A

balanced dessert wine will have far more acid and sugar than a balanced Cabernet Sauvignon, which in turn

will have a far more tannic structure than a balanced Pinot Noir. Even within a given varietal, there is no one

Platonic ideal-like balance point. Balance is also a matter of circumstance. A wine that has excessively

prominent tannins or acid when tasted alone might actually be a perfect compliment to a robust or rich meal.

Furthermore, balance is not an immutable property of a wine. Wines can come into balance. For example,

tannic wines can soften with time.” (2) “While there are guidelines for determining if a wine is balanced, there

will never be a set formula. With this in mind, the only real way to determine balance in a wine is to taste it.

Once engaged with a wine, factors that I find particularly germane are structural: tannins, acid and weight.

Paramount is how these compare to one another. I ask, is one feature clearly distracting or unsatisfying? The

ultimate test: If I continue to want to refill my glass with a particular wine over the course of a meal, it is

probably in good balance.” (3) “What constitutes a perfectly balanced wine is subject to personal preference,

regional and cultural norms, fashion, and circumstance. Therefore, it is not clear what a ‘naturally’ balanced

wine would refer to. For example, harvest maturity, oak treatment, and blending choices are all conscious

decisions a winemaker makes with the intention of achieving a particular balance point. In our own

winemaking at Dehlinger, we spend a significant amount of energy fine-tuning balance through the blending of

our many lots of Pinot Noir. Primary concerns include clarity of fruit, desired textural profile and acidity.

Combining various lots can accentuate or play down a feature that may be more or less prominent in a

particular individual lot. Determining the balance of the final wine requires numerous permutations of trial

blends tasted on various occasions, both with and without food.”

Laura Volkman, Winemaker, Laura Volkman Wines, Chehalem Mountains, Willamette Valley. (1) “In my

experience, balance involves four components: alcohol, fruit, acid and tannin. As a winemaker, we look to

preserve the fruit components and use the other three to complement the fruit. In Pinot Noir, for example, we

are trying to show off the delicate fruit components that can be negatively affected if the other three (alcohol,

acid and tannin) are too high or low. A high acid wine would taste salty, the fruit would be buried, and the

tannins would seem harsh. A higher pH, lower acid wine tends to have supple flavors and tannins. I have

made some wines with a pH of 3.9 that were not flabby because the fruit was strong. It was a hot season, the

brix were higher which translated to higher alcohol, and the acid was lower. This wine was naturally balanced.

We know that a high alcohol wine can taste “hot” on the finish and diminish the delicate fruit flavors and

sometimes overpower the aromas as well. A wine with too much tannin can be so astringent on the finish that

the fruit components are buried under a thick layer of over-extracted skins and wood and the finish is

negatively affected. These wines are usually cellared many years and over time the tannins will soften, but the

fruit will diminish as well.” (2) “My idea of a balanced Pinot Noir is based on my palate as well as chemistry

tests. The chemistry would look something like this: Alcohol 13.5% - 13.7%, pH 3.6-3.8, and 35%-50% new

oak depending on the intensity of the fruit. For my vineyard site, these numbers are common when carrying

two tons per acre in a typical year. The vineyard is always key for dialing in the fruit flavors and aromas.

Carrying less fruit such as in 2010 made some really nice wines even though it was a cool season. I harvested

a mere 3/4 ton per acre compared to my typical 2 tons and the wines are very nice!” (3) “A wine can be

naturally balanced but the key is managing the vineyard. That is the hard part. Everything else is cake!”

Jeff Brinkman, Winemaker, Rhys Vineyards, Santa Cruz Mountains, California. (1) “Balance is probably

the toughest part of winemaking to evaluate. I would argue that in the New World it’s almost an empty

descriptor, with very little heed paid to what it really means. When I see people talk about balance, it often

conforms to what they like. I like this wine, then this wine is balanced. In that usage, it is simply another

subjective analog to ‘what I like.’ The real question is whether or not there is an objective meaning to the term,

and I believe there is. The easiest way I can think to describe balance doesn’t have to do specifically with

aromas or flavors, but a more holistic view of the wine. That means the acidity, tannin, alcohol, etc., are

intertwined with aromas and flavors to provide balance. Is there too much oak? Too much alcohol? Do you

notice any particular component that doesn’t seem to fit? Then it’s not balanced. As a result, I think far fewer

wines are truly balanced than what’s given credit for.” (2) “The determination of balance to me is arrived at by

an evaluation of the seamless quality of the wine. If components are not knit, then the wine is not balanced. I

think comments like ‘There is a lot of oak, but it is well hidden,’ and ‘There is some alcoholic heat but it is

buffered by the fruit,’ are indications that the wine really isn’t balanced.” (3) “I think natural balance is practically

the only way to achieve balance. I don’t think you can add much balance in the winery; you can only take

away. For me, there is no ‘free lunch’ when it comes to winery treatments. Anything you do to a wine, any

addition or processing, is going to effect the end product. I think you can probably make small ‘nudges’ in the

winery, but you cannot construct a balanced wine ex nihilo in the winery. I firmly believe that vineyard work is

the route to balanced wine.”

Jason Drew, Winemaker, Drew Family Cellars, Anderson Valley, California. “ You’ve asked some very

provocative questions for which there are perhaps more than one answer. So let me see. There are the short

answers and those that require more time and thought. I’ll try to keep it somewhere in the middle. Here are

my musings.” (1) “Balance is very much a weight issue as well as a feeling for me. When I taste a wine, I feel

that it is at its best balance when it is not too light and not too heavy. The wine should seem fresh and

pleasant. The wine should float across the palate and not sink or wash out too soon. In addition, the wine

should have a mouthwatering effect. The ethereal notion comes to mind when thinking of balance: the feeling

of liquid hovering across the tongue and palate. In addition, there must be proper alignment of the three forces

of wine. The fruit weight, tannin structure and acid must all be in rhythm and aligned so that the wine appears

seamless. Fruit flavors must also be in tune, meaning fresh and pleasant as to not throw the other two

elements out of rhythm. The ripeness level must also be in ‘the zone,’ not too ripe and not too under ripe.

Better a little under ripe than over ripe as the wine will fade faster if over ripe. If a wine at first doesn’t appear

to be balanced, it will more likely come into balance if less ripe than over ripe. A tight rose bud will blossom

and a rose that has already blossomed will fade away.” (3) “A wine can most definitely be naturally balanced,

although for some reason, the majority of wines produced are probably not naturally balanced. Natural

balance should be the ultimate goal of every winemaker. To achieve natural balance, two things must be ideal:

the correctness of the site and the timing of harvest. The harvest date is the most critical and not given enough

credence. One false precept is that the fruit should taste ripe at the time of picking. I believe if the fruit tastes

at its best on the vine, it is too late to achieve natural balance in a wine. Great florists do not pick roses when

they are their showiest, rather when they are still a closed bud. The same with wine. If the grapes taste their

best on the vine, the wine will fade too quickly. At first the wine may taste wonderful, but after a few months in

the cellar the wine will tire, lose its vitality and fade quickly. Once the grapes become must, there is a whole

new ripening that takes place and once the wine becomes vigorous with new life, the chemistry changes

dramatically. The aromas, flavors, tannins and most definitely, the acids change. The grapes almost have to

be unripe for the acids to develop properly, turning the wine into a harmonious natural balance. There are

ways to help bring a wine back towards balance if the vineyard is poorly chosen, the vineyard is poorly farmed,

or the grapes are picked too late. There are three main components that winemakers can change: tannin,

alcohol level and acid. Once one component is changed, it will affect the other two, creating the potential for a

more unnatural state of balance.”

Paul Lato, Winemaker, Paul Lato Wines, Santa Maria Valley, California. Paul did not address the questions

specifically but expounded in a free form fashion. “Balance in wine is as important as in life. Unbalanced

wines are not worth drinking in my opinion. We can find balance in wine on many levels of ripeness and body

(light, medium, full). There are many possibilities. To understand balance, I recommend biking, surfing, yoga

and tango dancing. For me, to find balance in wine, it is always a mix of natural chemistry or numbers in the

wine, and my intuitive BLINK like experience. For a more esoteric understanding of this very interesting topic, I

recommend contemplating sculptures of American artist Richard Serra: huge sheets of metal that give us an

illusion of lightness and harmony.”

David Lloyd, Winemaker, Eldridge Estate, Mornington Peninsula, Victoria, Australia. (1) “I do not have a

working definition of balance. I perceive a wine as balanced when flavors and textures are what I like. Some

want more body and tannins than I do. So we all have a different sense of balance. For example, I am not

particularly keen on Burgundy from Gevrey Chambertain as it is too tannic and big for my palate, but I love

wines from Volnay and Chambolle Musigny.” (2) “I like a Pinot Noir to express its sense of place and history

without anything else providing a distraction. Distractions in wine are caused by excessive alcohol, body, acid

and tannin. I can and may like a Pinot Noir at 15% alcohol if it does not show the heat. However, from my

experience, I would be very worried about cellar aging a wine with over 14.5% alcohol. Each vintage the

winemaker should assess the timing of harvest, the oak to use and maybe whether any whole cluster is to be

added. My experience suggests that I am happy with flavors, body and acid at 13% alcohol in some years, yet

in other vintages I have found this as high as 14.2% alcohol.”

Wes Hagen, Winemaker, Clos Pepe Estate, Sta. Rita Hills, California. (1) “Balance is different to each

taster. It’s what keeps us coming back to the glass and helps a wine elevate the food experience that we share

with the wine. Balance is different with cheese, meat, a spicy dish, even a mood or company. Independent of

the social setting, wine balance means that the fruit body and finish of a wine are in equilibrium, and the wine

tells a whole story with a start, middle and finish. Balance is also different by price point. I don’t expect a story

from a $5 bottle, but I certainly do from a $50 bottle. Like a great film, we don’t think about plot, props or

actors: we are lost in the story and the moment and the craft becomes our reality, even if it is fleeting.” (2) “I

determine if a wine is balanced by the lack of pointy edges. The wine’s fruit, body and finish are seamless and

not clunky or obviously out of whack. The wine goes down effortlessly, matches the meal, and the glass

empties and refills almost by magic.” (3) “Great wine is naturally balanced by viticulture, provinence and

vintage. Vinification cannot balance a wine in a profound sense. It can mediate problems or mistakes in the

field, but a perfectly balanced wine is not manipulated into balance. It is balanced in the field, in the bin, in the

fermenter, in the barrel, in the bottle, and in the glass. Vintage, especially in Pinot Noir, is meant to be

celebrated and respected. Overt ripeness homogenizes both vineyard and vintage character, so part of

balance has to be a respect for time and place via a light hand in allowing a Pinot Noir to show where and

when it was grown, not the heavy-handed insistence that a wine impress only with color and extract.”

Brian Marcy, Winemaker, Big Table Farm, Chehalem Mountains, Willamette Valley, Oregon. “These are

great questions and really get to the heart of making wine properly.” (1) “Balance for me is the key component

in any wine to be delicious no matter whether it is a small and simple, or deep and complex wine. To me, there

are four aspects that must be in equal proportion to achieve balance: aromatics, palate entry, mid palate and

finish. If any one is missing or flawed or overpowering, even an untrained palate will recognize this and reject

the wine. I believe that we naturally recognize balance as beauty in all things including art, music, nature,

people, and food. Wine is no exception. I continually taste my wines, from the day the fruit is palatable in the

vineyard, throughout processing, elevage, and of course, after bottling.” (3) “I believe that a wine should be

balanced naturally through appropriate viticulture that is responsive to vintage and vineyard site. I compare

tasting grapes for winemaking to biting into a peach. We inherently know when it is too early, too late, or just

right. When starting with ‘just right,’ the vinification is easy and my job becomes staying out of the way and not

screwing things up. Just guide the wine with gentle nudges. Of course, give the same grapes to two different

winemakers and you will end up with two different wines, but the two wines will have basic structural

similarities. Recognizing the qualities of the fruit before vinification starts is important in making small

adjustments to capture the essence of a vineyard and vintage. Understanding beyond our inherent ability to

recognize balance, the relationships of acidity to tannin and sweet to bitter and of course the food that wine is

ultimately intended for, is part of the art.”

Steve Doerner, Winemaker, Cristom Wines, Salem, Willamette Valley, Oregon. (1) “ Balance to me is

easier to describe what it is not. Basically, if none of the 300 components you reference are obvious, then the

wine is balanced. If, however, one or just a few of them are overwhelming, the others, I would say the wine is

out of balance.” (2) “Unfortunately, balance is determined by how the wine is perceived, which is different from

one taster to another. If one person is much more sensitive to a particular substance relative to another then

by my above definition, one person may perceive a wine to be balanced, while another will not.” (3) “Yes, wine

can be naturally balanced which is always the hope. Again, as you pointed out, there are many different

components in wine and we can only control a few of them. However, we can as vintners try to get close to a

balanced wine (if it’s not naturally) by adjusting the major components. The ones that we can control to any

significant degree would be alcohol/sugar, acid and some phenolics. There are some others that we can

control to some lesser degree but beyond that each wine is unique. If you ask me, I like it that way. I hope

winemaking never becomes simply a matter of controlling all the variables.”

Theresa Heredia, Winemaker, Freestone Vineyards, Sonoma Coast, California. “I think that because most

people have an understanding of what balance means in general, they can probably deduce what the term

means when used regarding wine.” (1) “ My definition of balance: harmony; equilibrium; no single component

dominates the experience. When thinking of balance, I primarily consider acid, tannin, alcohol, oak and

concentration of fruit flavors. I consider a wine to be unbalanced if one component, such as alcohol, acid,

tannin, fruitiness or oak stands out and dominates the wine experience. I’ve never experienced this, but some

folks say that if a wine has 15% or 16% alcohol, it can still taste balanced if it has enough fruit concentration,

perfume, tannin and acidity to balance it out. Another example would be a wine that does not have enough

acid but has a lot of tannin. Wines like these can taste ‘fat’ or ‘flabby’ and ‘dry.’ Wines with low acidity often

taste ‘soapy’ and this makes it difficult to find the subtleties in the wine. The same can be said of wines with

too much acid, too much tannin or too much fruit concentration. Too much fruit extract can also make it hard to

experience subtleties of the wine.” (2) “I determine if a wine is balanced by taste and smell. For example, if a

wine with a quite a bit of tannin has a good amount of acidity, the perception of the tannin is less ‘dry’ because

though the tannin is astringent and has a drying effect on the palate, the acid makes us salivate and thus

‘balances’ the tannin.” (3) “Yes, a wine can be naturally balanced, given the right conditions during the growing

season and at harvest. If the weather is not too cold, too wet or too hot, the grapes can be harvested with just

the right acid, sugar and tannin to create a wine with impeccable concentration, aroma, tannin, alcohol and

acidity. When this happens, the winemaker has to do little to make a wine with great balance. The role of the

art of vinification in times like these is quite simply, not to interfere, and just manage the temperature and health

of the fermentation. In difficult years, when the wines are not naturally balanced, the art of vinification plays a

big role in terms of manipulation to find balance. One can achieve balance through the type of maceration

such as punching down, pumping over, stirring (white wine), pressing regime, acid additions, water additions,

oak selection and time in oak, temperature of fermentation, and duration of fermentation/maceration.”

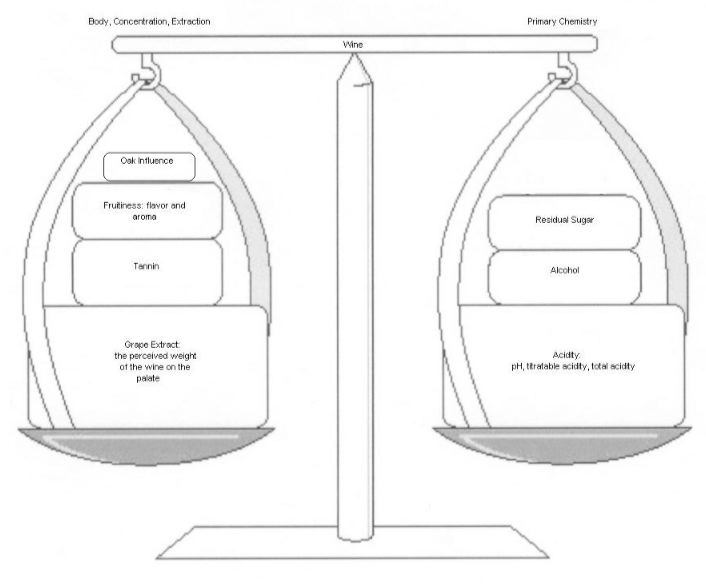

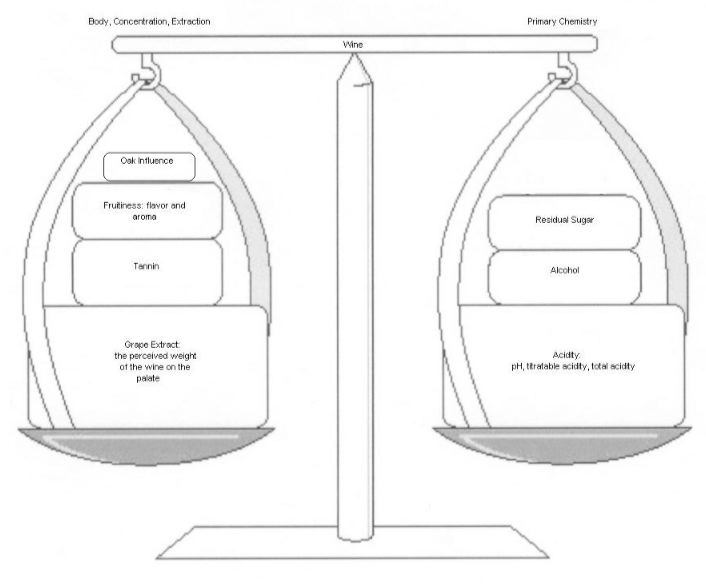

Theresa contributed this diagram:

Ted Lemon, Winemaker, Littorai, Sonoma Coast, California. (1) “Both powerful and delicate wines can be

balanced. Neither has cornered the market on wine balance. The key is that all elements are in proportion,

whether they are in delicacy or in power. Each of us has different sensitivities to all components in wine so for

what is balanced for one taster may not be for another. For me a wine is balanced when no element outweighs

the others. Wine is most balanced when consumed at the perfect moment of its aging curve when all elements

are in perfect harmony. Therefore, wines are not necessarily inherently balanced, but achieve moments of

balance during their lifetimes.” (2) “I look for seamlessness in wine. As noted above, it is achieved when no

element is out of proportion.” (3) Since wine is not ‘natural’ but a product of human interaction with nature,

there is no such thing as a naturally balanced wine. Mastery of the proper moment to pick, of tannin extraction,

of whole cluster usage, and a host of other aspects of vinification lead to the potential for balance.”

I told Ted I had heard the statement, “If a wine is not balanced initially, it will never be balanced.” Ted’s

comment above that wines achieve moments of balance during their lifetime seemed to contradict this. I asked

him to reply and I find his answer to be enlightening.

“To say that a wine must be balanced initially to be balanced later implies two things. First, that all elements in

wine evolve at the same rate, no matter what constituent is involved. Clearly, this is specious because we all

know that tannins, for example, tend to decrease over time, but alcohol, for example, does not. Since different

constituents change at different rates, a wine that does not appear balanced now may later be so.”

“The wine world is full of examples of wines that need time to come into balance: the great Rieslings of

Germany, Port, the Chenin Blancs and Cabernet Francs of the Loire from great vintages, traditional Barolo, etc.

To claim that wines must start out balanced to be balanced is a convenient way to dismiss wines that don’t fit a

simple mode of wine evaluation. If this sounds like a veiled criticism of a certain school of wine reviewers, well

I don’t mean for it to be veiled.”

“The second implication of the statement that a wine must start out balanced to be balanced is that wine

always evolves in ways that are predictable. In other words, it is to deny wine (and Mother Nature) its

unpredictability and genius. Wine is alive. It changes, thank the Lord. To say wine must start out balanced is

to deny its living nature. Vintages are full of surprises. Ugly ducklings become swans. Swans lose their allure

far earlier than we expect.”

“I think this myth has grown so widespread for two reasons. One is that it is true that many balanced wines

age well and undoubtedly better, on the whole, than wines that do not seem balanced. So in the great scheme

of things it is a ‘safe’ statement. The other reason I think, goes back to our beloved Pinot grape. Henri Jayer

gained nearly mythological status during his lifetime. While I am an unabashed admirer of Henri’s wines and

his philosophy, I don’t think he ever cornered the market on producing the world’s greatest Pinot Noirs. Indeed,

the fact that DRC is in the very same village, making wines in a completely different style and yet at least as

profound, speaks volumes. Henri’s greatest wines were wonderful. In my mind, his lesser wines were lovely,

but not profound. Henri was, as you well know, a huge proponent of this balance idea which then deeply

influenced Robert Parker in his youth. Bob loves to point this out.”

“There are so many wonderful winemaking styles in the world. No one house has ever got it all right. Some

that do very well every year never quite soar to the heights. Even within a vineyard, site expression can

change quite dramatically from one year to the next. Some years are more tannic, others softer, others more

driven by acidity. Which years are the best years for a given site? Does Thieriot Vineyard do best in the tannic

years since it is by nature a more generous wine? Does Hirsch Vineyard do better in the soft years since it is

by nature a tannic wine? What about Nuits St. Georges Les Porrets? One could be driven mad by all the

different permutations possible. In the end, the terroir-driven winemaker has to step back from such

considerations which might lead to radical changes in winemaking from year to year and simply accept to let

nature take its course with the winemaker’s gentle guiding hand on the tiller.”

“In any tasting of wines of terroir, we face a daunting task. Winemakers are children playing with the gifts of

God. When we taste the fruits of their labor, we ask that they step out of the way. We ask that the stumbles

and temper tantrums of the vintage, the challenges of harvesting, fermenting, pressing and aging should

proceed as smoothly as possible. And we ask that our winemakers should leave behind in the bottle no trace

of their failings, but only the beautiful expression of the places where they have been.”

Consumers chime in:

DS. (1) “Balance to me is the delicate confluence of extraction, acidity, tannin and hopefully terroir (that sense

of earth/place). Great balance comes across as having substance without excess heaviness, a sense of

WEIGHTLESSNESS which is so rare in Pinot!” (2) “The initial aromatics provide a pretty accurate indication of

balance. Then extensive swirling and sipping. If possible, let the wine breath and open up. Balanced Pinot

will usually open up and get better with air. Ultimately, balanced Pinot is instantly recognizable as a wine I

could actually drink with food all day without feeling fatigued after half a glass and just as importantly, not a

wine that overwhelms the food!” (3) “Balance is everything to me. Otherwise I feel I’m simply jerking off,

wasting my time and money. I think the problem is that the majority of drinkers have no idea what balance is

and how to recognize it. Recognizing balance requires years of tasting and being exposed on occasion to

balanced wines in start contrast with the majority of West Coast Pinots.”

KJ. (1) “Balance is how the fruit, tannins, acidity and alcohol work together.” (2) “Taste and mouth feel

determine if the wine is balanced.” (3) “I think balance is innately what one looks for as that is what makes a

wine delicious.”

ELH-H. (1) “Fruit = Acid.” (2) “If the wine is too hot (too much alcohol) it is unbalanced. If the wine has too

much wood or fruit, it is unbalanced.” (3) “YES!”

CL. (1) “I feel that a wine is well balanced when no wine feature overpowers another one. Flavors, tannin and

acidity all form a perfect harmony.” (3) “I guess so.”

AH. (1) “I think of balance as the interplay between the rich and sweet fruit flavors that make wine pleasurable

and the structural factors (acid, tannin) that make wine intellectually interesting. A wine too far in either

direction can be unpleasant, but a great wine becomes more than the sum of its parts by being in balance.” (2)

“I determine if a wine is balanced by tasting it over the course of an evening. Different elements can stand out

at different times, so letting the wine breath a little can be important.” (3) I think balance is especially important

in Pinot Noir where acid tends to run high. Under ripe Pinots can be over acidic without the fruit to balance.”

MS. (1) “Balance in wine is when no one attribute stands out too much. Whether the wine is too oaky, too

acidic, too fruity (depending on the varietal), or not fruity enough, or overpowered by winemaking techniques

such as malo.” (3) “I look for balance in every wine I taste. If there is oak, then I prefer just hints of the

essences of oak (caramel, nutmeg, vanilla, etc.) and dislike the wine to taste like oak chips. There is nothing I

hate more (and it happens all the time) when I buy a $100 bottle of Pinot, open it at dinner, and have it taste

like fruit at first, then an overwhelming finish in caramel candy. It ruins my experience of the wine because I

ordered Pinot to pair with my meal and to complement it, not to have it taste like candy.”

DS. (1) “For me personally, a balanced wine contains the right and appropriate fruit flavors, oak (or not),

alcohol, acidity and pH from the moment we sniff, fill our mouths and swallow. All are very well integrated and

each layer of flavor is perfectly matched.” (2) “Sniff, swirl and sip. A balanced wine is bright, enticing with a

wonderful and full mouth feel and each component not overpowering the other: harmonious from start to

finish.” (3) “Absolutely. If a wine is disjointed or seemly unbalanced, my tongue is not pleased, nor is it a

pleasant or memorable experience. For me, wine is about the experience, the company, the food and the total

feeling. What makes for even a more rich wine experience is having a well-balanced wine excellently paired

with a meal shared by friends and family.”