PinotFile: 6.19 March 19, 2007

|

Buena Vista Carneros: A Remarkable Saga“California can produce as noble and generous a wine as any in Europe” These were the words of Agoston Haraszthy (Ah-gus-tun Harris-tee), first published in 1862 in his historic report to the Senate and Assembly of the State of California, titled Grape Culture, Wines, and Wine-Making. Haraszthy had been given the title of “Commissioner on the Improvement and Growth of Grape-vine in California,” and sent to Europe to examine the different varietals planted there, to study the viticulture of the time, to examine the various methods employed in making wine, and to purchase vines to bring back to California for propagation and planting. Some of his observations on this trip were truly visionary for the time. He noted, “Frequent consultations with many eminent men in Europe, assured me that the quality of the grape governs in a great measure, the quality of the wine.” In addition, he remarked that, “Various examinations confirmed my previous conviction that California is superior in all of the conditions of soil, climate, and other natural advantage, to the most favored wineproducing districts of Europe. All this State requires to produce a generous and noble wine is the varieties of grapes from which the most celebrated wines are made, and the same care and science in its manufacture.” His was the first book to announce to the United States that California had the potential to grow and produce fine wine, and it became a major reference for students of enology and viticulture for many years.

Over the years, this Hungarian immigrant’s legend grew to storybook proportions, in part because Haraszthy was a clever self-promoter. He became known as the “Father of California Viticulture,” and “Father of Winemaking in California.” James Beard called him “The great name in California wine history.” Fortunately, Brian McGinty, Haraszthy’s greatgreat- grandson researched Haraszthy’s biography for years to find the details of his life in Hungary, Wisconsin, California and Nicaragua. In 1998, he published, Strong Wine. The Life and Legend of Agoston Haraszthy, the definitive history of this remarkable man’s life. McGinty’s approach to documenting Haraszthy’s life is commendable, for he tries to clarify many issues that separate truth from legend. I have excerpted much of my information in this feature from this excellent book and any wine aficionado would find it a fascinating read. In addition, Haraszthy’s Grape Culture, Wines and Winemaking is in publication. This book has a concise summary of Haraszthy’s life and influence written by Dr. Stephen Krebs. The text itself is of great interest only to dedicated wine historians. Over time, Haraszthy’s legend has grown in stature. McGinty writes about him, “Bold, flamboyant, extravagant, devious, visionary, Agoston Haraszthy (1812-1869) is one of the most fascinating - and elusive - figures in the history of American agriculture.”  Much of what has been said and written about Haraszthy can be divided into Truths and Legend: Truths: * He was the first Hungarian immigrant to settle permanently in the United States. * He was the second Hungarian to write a book about the United States in his native language, titled Travels in North America. * He was the first operator of a steamboat on the upper Mississippi River. * He was the first Town Marshal and County Sheriff of San Diego, California. He built the first city jail in California while in San Diego. * He was the first assayer of the United States Mint. * He built the first hillside caves in California. * He planted more than 1,000 acres of vineyards. * He introduced more than 300 varieties of European grapes to California. * He was the author of the first book on wine written by a Californian. * He was the first commercial wine producer who recognized the potential for a world-class wine industry in California. * For a few years in the 1860s, the Buena Vista Estate was the largest vineyard in the world. His “wine estate in Sonoma was a commercial failure, but he was the first to plan and attempt such a grand scheme. * He was the first to instruct winemakers in the best ways of planting, cultivating, and harvesting grapes. Legend: * He claimed to be a Hungarian count, but he wasn’t - he was a Hungarian nobleman from one of the oldest families in Hungary. * He was not a member of the Royal Hungarian Bodyguard. * He was never imprisoned in his native land. * He was called “Colonel” in California and Nicaragua but the source of this title has never been adequately explained. He probably had some service in the Hungarian army, but the title was more likely just a courtesy one. * He did not come to the United States as a political refugee. He did not flee to the United States after aiding the escape of a Hungarian separatist who had been jailed by the government. * He was not the first to import grapes into California. * He was not the first to grow grapes and make wine in California. * There is no evidence that he was the first to bring in and plant Zinfandel and Pinot Noir. Despite the legend that has developed and the inaccuracies therein, the accomplishments of this man can not be discounted. The best way to review his life and the origins of Buena Vista Carneros, is through the perspective of a timeline which follows. The Life & Times of Agoston Haraszthy and the History of Buena Vista Carneros 1812 Agoston Haraszthy de Mokesa (Haraszthy) was born to an aristocratic Hungarian family. 1840 Haraszthy arrived in Wisconsin as a 27-year-old and founded the city of Harasztopolis. Here he is credited with the importation of hops plants and the introduction of sheep. He authored his book on America here. He married a noble woman from Poland on a trip to Hungary and had three sons born to him in Wisconsin. 1849 Haraszthy traveled to Southern California by wagon train, probably because the California wine industry was centered here at the time. 1850 Haraszthy purchased land in the Mission Valley area of San Diego and planted fruit trees and grapevines. The grapes were the Mission variety sourced locally, and Vitis vinfera which he brought in from the East Coast. 1851 Haraszthy became involved in politics and as a State Assemblyman traveled frequently to Sacramento. 1852 Haraszthy purchased 50 acres 2 miles south of the city of San Francisco and later an additional 160 acres. He named the ranch Las Flores. The area proved to be unsuitable for growing wine grapes. 1853 Haraszthy bought land in the hilly peninsula south of San Francisco called Crystal Springs. He managed 640 acres and planted about 30 acres of grapevines. By 1854, he had 500 rooted vine cuttings, both Mission and European varieties. The first planting of Zinfandel in California may have occurred here, but this cannot be substantiated. Again, the vineyard failed. He traveled to Sonoma Valley and became convinced that this was the ideal location for producing wine. 1856 Haraszthy bought land northeast of the town of Sonoma and named it Buena Vista Farm. Buena Vista means “Beautiful View” in Spanish. The views of the Sonoma Valley and San Pablo Bay were spectacular. The property consisted of 1,000 acres of valley land and 4,000 acres of hillsides. He transported vines from Crystal Springs to the vineyards of Buena Vista. 1857 Haraszthy relocated to Sonoma. He planted 16,850 vines, both Mission and European vinifera and had a nursery with 300,000 rooted native vines and 30,000 foreign vines. The total collection of vines in the vineyard and nursery was reported to consist of 165 different varieties. He made 6,500 gallons of wine and 120 gallons of brandy using redwood barrels with resins removed. 1858 An additional 40,000 rooted vines (60 acres) were planted at Buena Vista. His total plantings were 100 acres, a large vineyard for California at the time. The vineyard was among the two or three largest, and maybe the largest in the state. He ultimately wanted to plant 1,000 acres. He used Chinese laborers from 1857-1862 to excavate hillside cave cellars, possibly the first in California. These stone hillside cellars were damaged by the San Francisco earthquake in 1906 and were restored in later years by Frank H. Bartholomew. In 1858 he wrote the definitive manual on viticulture and winemaking, Report on Grapes and Wines in California. In this manual he emphasized a scientific approach to growing grapes. 1859 Haraszthy entered wines in the State Fair in Sacramento and won six awards including a silver cup for best first-class wine among all entered in the fair. He sold land to Charles Krug (35 acres for $1,000). Krug eventually sold his Sonoma vineyard and moved to the town of St. Helena in 1860. Hereszthy sold blocks of land in Sonoma to others including Jacob Gundlach and Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo. This same year, John Pritchett built the first stone winery in the Napa Valley 1860 Haraszthy won first place award for best white wine and brandy at the Sonoma County Fair. He produced California tokay, port, champagne, brandy, and still wine using a blend of Mission and European grapes. 1861 Haraszthy embarked on a fact-finding trip to the wine regions of Europe on June 10, 1961. His trip included visits to Dijon, Gevrey-Chambertin, and Beaune in Burgundy, and other regions of France, in addition to Germany, Switzerland, and Italy. He was to remark about Burgundy, “Industry and science have in modern times elevated the Bordeaux ... but, nevertheless, the Burgundy is sought for by all nations, and the extensive district planted with its vines cannot supply the wants of the trade.” He referred to Pinot Noir grapes as “Pineau” and “Noirere.” Regarding pigeage, he said, “When they have remained in this (fermenting) tank from 24 to 40 hours, the fermentation will send the stems and seeds to the top of the vessel, forming a hard mass. Then according to the size of the tank, from 4 to 10 men, stripped of all of their clothes, step into the vessel, and begin to tread down on the floating mass, working it also with their hands.” (Now we know why pre-phylloxera Burgundy tasted so great.) 1862 Haraszthy presented the account of his European trip to the State Legislature in Sacramento, Grape Culture, Wines and Wine-Making. This contained an updated version of his 1858 Report on Grapes and Wine of California and the official report given to Governor Stanford. The Legislature voted not to reimburse Haraszthy for his expenses including the cost of his vines, and rebuked his offer to provide instruction on winemaking and viticulture. He had built a stock of 300,000 rooted vines ready for distribution consisting of about 350 varieties such as Cabernet, Pinot Noir, Riesling, Chardonnay, Merlot, Gewurztraminer, Muscat, Sauvignon Blanc, Semillon, Sylvaner, Carignane, and Furmint. Some of the varieties were already in California at the time, but some were completely new to the state. It was his intention to sell and distribute the varieties throughout the state. As President of the California State Agricultural Society, he wanted to establish a state-sponsored horticultural garden where grape varieties could be tested, propagated and made freely available. Unfortunately, without state support, his aspirations were doomed to failure. 1863 At this time, the wine industry experienced a severe economic depression and Haraszthy also encountered financial problems. He had formed a partnership with investors headed by banker William Chapman Ralston hoping to save his operation. Named the Buena Vista Viticultural Society, this infusion of money allowed him to expand his vineyard to 6,000 acres including an additional 85 acres of European vinifera grapes. He tried to enter the Champagne market at this time but the attempt failed. In the 1860s, phylloxera began to appear in Califonia vineyards. In fact, Buena Vista may have been the first vineyard in the state infested by the root louse. Phylloxera could have been brought into California by Haraszthy in the European vines he imported. Since Old World vines had no resistance to phylloxera, the pest destroyed a majority of California vineyards during the 1870s and 1880s. 1864 Haraszthy traveled to the East Coast and spoke to the American Institute in New York. He emphasized that “the quality of the soil makes a vast difference in the quality of wine,” and recommended Pinot Noir as the preferred grape for making red wine in the style of Burgundy. The reporters at the event were subsequently to refer to Pinot Noir as “Noiree,” “Pignon,” “Noriai,” and “Pinio.” 1865 Haraszthy layered the vineyards at Buena Vista to increase production. 1866 Haraszthy suffered a near-fatal fall at Buena Vista. He was forced out of the Buena Vista Viticultural Society. 1867 Haraszthy left Buena Vista at age 54, essentially bankrupt. Those who followed him at Buena Vista thought phylloxera was due to close spacing of the vines and tragically, they plowed under every other row in the vineyards, most of which were vinifera varieties. 1868 Haraszthy traveled to Nicaragua by boat. Here he began making distilled spirits from sugar cane for export at Hacienda San Antonio. His sons, Arpad and Attila, continued to make wine in Sonoma at the estate of General Williams. 1869 Haraszthy was granted bankruptcy in California. He mysteriously died at the age of 56 in Nicaragua. Theories abound, but it would seem that he either went out into a stream and was devoured by a shark or alligator, or drowned, or was the victim of foul play. The alligator theory seems to take precedent in most written accounts. 1876 Buena Vista Viticultural Society was liquidated. 1880 Robert and Kate Johnson purchased the Buena Vista property and built a mansion on the site called “The Castle.” 1906 The earthquake and phylloxera put an end to winegrowing at Buena Vista and the property was left to the Catholic Church which in turn sold it to the State of California. 1920 The State converted the property including “The Castle” into the State Farm for Delinquent Women. In time, the castle structure burned to the ground. 1943 The property was neglected over time and used for cattle grazing until the land and the Buena Vista Winery was purchased by Frank H. Bartholomew, Vice President of United Press. While on a trip to San Francisco that year, he saw an auction sale of 435 acres and a building in Sonoma for only $17,050 ($39 an acre). He bid and won the property rights sight unseen, and didn’t visit the Buena Vista property until after WW II. He restored the property and its vine yards, replanted, refurbished the winery and made wines by 1947. Andre Tchelistcheff was the consulting winemaker. The winery became profitable under Bartholomew’s direction. Bartholomew knew little about the wine business, yet he had a tremendous impact on the future of Sonoma Valley winegrowing. 1955 Bartholomew was promoted to President of United Press. 1968 Young’s Market Co, LLC, bought the Buena Vista label and winery from Bartholomew who retained most of the vineyard acreage. Bartholomew subsequently started a second winery project in Sonoma called Hacienda. 1976 A state-of-the-art winery was built at Buena Vista in Carneros. 1979 Buena Vista was sold to A. Racke Gmbtt & Co. of Germany, a family-owned wine and spirits business, founded in 1855. E & J Gallo and a company in Australia were also in the bidding. Marcus Moller-Racke directed the project and Anne Moller-Racke became vineyard manager. 1983 Bartholomew penned a book, Bartholomew: His Memoirs, which was illustrated by Jan Haraszthy. 1989 Bartholomew’s widow, Antonia, directed the building of a reproduction of Haraszthy’s columned villa based on surviving photographs. This villa was opened in 1990 and has become part of a 500-acre park owned by the Frank H. Barholomew Trust Foundation. Gundlach-Bundschu took over Hacienda, and operates it on behalf of the Trust Foundation as Bartholomew Park Winery as part of the park at 1000 Vineyard Lane in the town of Sonoma. There is a museum associated with the winery featuring memorabilia from Frank H. Bartholomew. 2001 Buena Vista sold to Allied Domecq PLC. The purchase included 718 acres of vineyards, the largest vineyard holdings in the Carneros appellation, and the historic winery and tasting room in Sonoma ($85.5 million). The Racke family split off 250 acres to farm as The Donum Estate and grow grapes for the Robert Stemmler label. Ann Moller-Racke became director of the wine-growing program at The Donum Estate. 2003 Winemaking team headed by Jeff Stewart (formerly La Crema) arrives. 2004 Two new lines of wines are introduced by the winemaking team at what is now known as Buena Vista Carneros. 2005 Beam Wine Estates purchased Buena Vista and most of the management and winemaking team is retained. Replanting and redevelopment of the 1,000 acre Ramal Vineyard which straddles both Napa and Sonoma Carneros is begun. Production output is significantly reduced, and a new era of commitment to ultra-premium wine production is begun. And there you have it - 150 years of winegrowing tradition - making Buena Vista Carneros the oldest premium winery still operating in California. It is a true saga that features a “Count” from Hungary who was a viticultural hero to many, and a self-promoting scoundrel to others. It is a tale of the tribulations of a crafty immigrant who was driven to succeed and had an unrelenting passion for wine. He may have unknowingly brought phylloxera into California, but it was his teachings that set the stage for the dramatic successes in California wine production that followed in the 20th century. Then there was a journalist, Bartholomew, who, like Haraszthy, was largely uneducated about enology and viticulture at the beginning. Despite this, he was able to make Buena Vista a successful financial operation. Another immigrant surfaces in this saga, namely Andre Tchelistcheff, the Russian who, if he must defer to Agoston Haraszthy as the “Father of California Winemaking,” should at least be thought of as a legend in his own right. From start to finish, the history of Buena Vista is a remarkable tale. Could another wine movie find its inspiration here? Agoston Haraszthy was inducted in March of this year as part of the inaugural class of “founders” in the Vintners Hall of Fame in St. Helena, California. Other founders inductees include Brother Timothy (1910-2004), Charles Krug (1825-1892), and Georges da Latour (1856-1940). As an interesting side note, Dr Krebs, a noted viticulturalist, in his introduction to the reprint of Agoston Haraszthy classic work, notes that early explorers brought Vitis vinifera to the Americas from Europe. Colombus was thought to bring vines on his voyages and some of the vines grew vigorously in Haiti. Lord Delaware brought the first European grapevines to North America in 1619. The vines could not be successfully grown, presumably because of phylloxera and other diseases. Only North American species could be cultivated. The first European vinifera were brought into California by Spanish Padres from Mexico in 1767. The grape first planted was thought to be the Mission grape or Criolla. The initial plantings were at Mission San Diego and then spread northward as the chain of missions was established in California from San Diego to Sonoma from 1767 to 1833. Jean-Louis Vignes is credited with planting California’s first documented imported European grapevines in 1833. A large number of European varieties were brought into California in the 1850s and 1860s and were successfully grown here. Bibliography Agoston Haraszthy. Grape Culture, Wines, and Wine-Making (with Notes upon Agriculture and Horticulture), James Stevenson Publisher, Fairfield, CA, reprinted 2003, 126 pp. Brian McGinty. Strong Wine. The Life and Legend of Agoston Haraszthy, Stanford University Press, Stanford, CA, 1998, 476pp. Gerald Hill. Historical Column on the History of Winegrowing in Sonoma Valley, Sonoma Valley Sun, May 4, 2006.

Buena Vista Carneros TodayIn the 1990s, Buena Vista was turning out 300,000 cases of ho-hum wine. They certainly were not on the pinotphile’s radar. Their best wine had become a Sauvignon Blanc made from grapes in Lake County, not from their extensive vineyard holdings in Carneros.

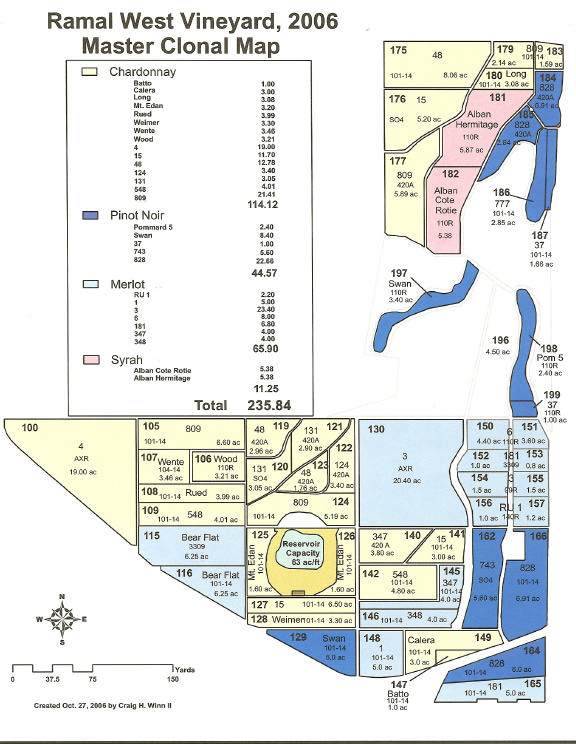

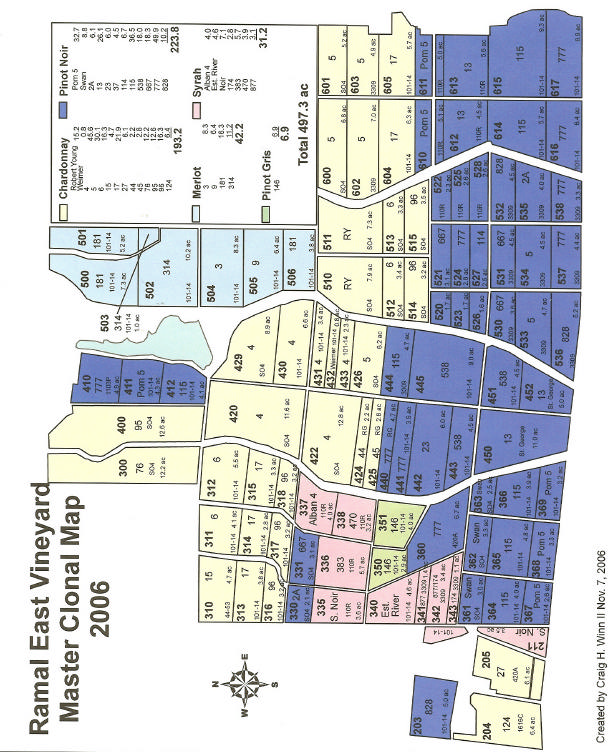

Today there is a dramatic remaking of the brand. Beam Wine Estates has contributed the corporate financial backing that has made it possible. The current CEO is production- driven, but also quality-oriented. The winemaking facility (pictured right) was built in the 1970s, one of the first wineries in Carneros. It has been completely modernized and now contains 62 5 to 10 ton open-top fermentors which have been installed in the former barrel room. This gives the winery the capability to have all of the wine from the estate, which arrives usually over a two week period, fermenting in unison. The Ramal vineyard is undergoing replanting with different rootstocks and clones matched to suitable sites on the estate property. The East Ramal Vineyard has 3 to 9 year old vines of Chardonnay, Syrah, Pinot Gris, Merlot, and Pinot Noir. The West portion of Ramal Vineyard is mostly all new plantings, expected to deliver fruit in 2006 for the first time. Here there is Chardonnay, Merlot, Syrah, and Pinot Noir. The vineyards are pictured and Clonal Maps of the vineyard are depicted on the next pages. Pommard is the workhorse clone here with other clones adding interest such as 115 (spice), 667 (structure), 777, 828, 583 (cherry) and Swan. They all contribute something to the mix. There are a total of 167 different blocks on the property, in essence, many different small vineyards within a large vineyard. Out of a total of 1,000 acres, 800 are planted or replanted and the last phases of replanting will be completed in 2008. Sophisticated viticulture technology is now employed including airplane-view (called “Vine View”) infrared mapping of vine vigor which can be used to guide

Top (ascending): new plantings, Buena Vista House for guests in background; view of new plantings looking southeast toward San Pablo Bay; Old vine; Bottom: fermentation tank room.

irrigation and picking. Better trellising and spacing of vines has been employed to stimulate balance and intensity. The emphasis is on farming for balance and quality now with lower yields in all vineyards (many blocks below 3 tons per acre), use of deficit watering regimes to create smaller berries, and the planting of natural cover crops to soak up water and add organic material to the soils. The current vineyard manager, Craig Weaver, is a Ohio native who has spent over 20 years managing vineyard sites in California. Jeff Stewart arrived at Buena Vista in 2003 after crafting cool-climate varietals at La Crema Winery in the Russian River Valley for five vintages. Prior to that, he made wine at Robert Keenan, Laurier, De Loach, Mark West and Kunde. Noted winemaker Chuck Ortman was one of his earliest mentors. Jeff grew up in the Lake Tahoe area of California. His high school chemistry teacher encouraged him to go into winemaking after a trip to France in high school sparked his interest in wine. It was a bottle of 1978 Romanee-Conti that convinced him to make Pinot Noir. Jeff is like a big friendly bear - a burly guy with a winning smile and an unrelenting enthusiasm for his work. His mantra is balance and he says, “As with many winemakers, I believe in balance, both in the vineyard and in the wines. I like to see power and elegance working together.” In early 2004, Jeff and the Beam Estates management team headed by Jim DeBonis, made the decision to discontinue the previous California Classic and Grand Reserve lines of wines, and reduce production to 45,000 cases. The two new lines of wines include: The Carneros Series, varietal bottlings of Chardonnay, Merlot, Pinot Noir and Syrah ($19-$21) and The Estate Vineyard Series (EVS) of limited release wines featuring select clonal material and/or blocks from the property ($37). New packaging and labeling create a modern and sophisticated tone.  The grapes here are picked in early morning hours, starting at 2:00 AM and finishing by 8:00 AM. The cold fruit that is brought in is fresh and sugars are slightly less than at mid-day. Intensive sorting is followed by de-stemming. Fermentation is carried out with both native and commercial yeasts. A Revinsa basket press is used to gently draw off the juice. All of the blocks are aged separately using about 35% new oak (mostly French, some Eastern European). Currently there are 20 clones of Pinot Noir on 40 blocks across 180 acres. I recently had the opportunity to sample several of the latest releases of Pinot Noir. There is tremendous potential here because of the vast vineyard acreage upon which to draw. With the infusion of modern farming technology and skilled winemaking, the future looks very promising. By 2006, only 40% of the vineyards were producing fruit so the wines tasted below only hint at the future quality of the wines to come. All of the wines have nice finesse and weight. There is no t n ‘a overload and the wines are nicely balanced. Mouth feel is particularly attractive. Once Jeff has all of the right grapes to work with, his ducks in line as they say, Buena Vista Pinot Noirs will be on every pinotphile’s want list. Agoston Hereszthy would have been proud.

2009 Brooks Willamette Valley Pinot Noir 14.3% alc., 2,600 cases, $22. 9 vineyard sources. Grapes were 100% de-stemmed and fermented in individual lots. Aged 10 months in 35% new French oak with some Hungarian oak. Unfined and unfiltered. · Moderately light reddish-purple color in the glass. Initially the nose offers demure but satisfying aromas of red cherries and berries, dried rose petals and a hint of baking spice. The aromatic intensity fades over time in the glass with a touch of alcohol rearing up. Medium-weighted red fruit flavors with a nice smack of cherry on the finish. Very soft tannins and a smooth mouth feel make for easy approachability. A fruit-forward wine offering a glimpse of the 2009 vintage in Oregon which offers more upfront charm than the 2008 vintage and higher alcohols. Good.

2005 Buena Vista Carneros Ramal Vineyard Pinot Noir 13.5% alc., $25. · A light style of Pinot Noir that takes on a fuller structure with time in the glass. Attractive cherry, toast and smoke notes are featured in the aromas and flavors. A thoroughly satisfying daily drinker.

2005 Buena Vista Carneros Ramal Vineyard Clone 5 Pommard Estate Vineyard Series Pinot Noiri 14.3% alc., $42. · A elegant Pinot Noir that is beautifully weighted. It rolls over the tongue like silk. Red and black stone fruits are featured with plenty of Asian spice. The balance is impeccable and the finish urges you to take another sip. The sensuality of Pinot Noir can be found here.

2005 Buena Vista Carneros Ramal Vineyard Clone 828 Estate Vineyard Series Pinot Noir 14.2% alc., $42. · The nose reminds one of freshly baked cherry pie but is rather closed at this time. There are interesting spice elements underlying the Pinot fruits. The wine is rather closed and not offering all of its potential charm. Some cellar time is necessary.

2004 Buena Vista Carneros Ramal Vineyard Pinot Noir 13.5% alc. 14,000 cases, $23. · An elegant style that is driven by cherries and strawberries in the nose and flavors. A little smokiness and herbs add interest to the nose and finish. This wine has a fairly rich mouth feel. With air time, the wine becomes quite silky and more fruity.

Buena Vista Carneros has a tasting room in the original winery stone press house (pictured below), located five minutes from the Sonoma Plaza Square. It is open from 10-5 daily and the phone is 800- 926-1266. You can drive out onto Ramal Road and see the Ramal Vineyard and Buena Vista winery, but tours here are by appointment. The 2005 Carneros Pinot Noir was released in December, 2006, but the other 2005 Pinot Noirs are not available as yet. The winery website is www.buenavistacarneros.com. Wines may be purchased on the website or through fine wine retail channels.

Devil or Angel Whichever You AreAt a recent Pinot Noir tasting event, I overheard someone say, “I like BIG Pinots!” As I went from table to table, some pourers touted the heft of the Pinot they were pouring, often accompanied with a smile that read “You are going to love this fruit bomb.” Somewhere along the line, “big” in reference to Pinot Noir has come to imply “better.” This was reinforced by a large tasting of Pinot Noirs published in the latest ( April, 2007) Wines & Spirits magazine. (This wine publication, by the way, has outstanding feature articles on wine, the best written examples of this genre currently offered in my opinion.) Here are the descriptive terms used for some of the devilish Pinot Noirs that received admirable scores: “richly extracted,” “a big pinot,” “this one is as fat in the haunches as a Porsche Carrera,” “the first impression is alcohol, extract and oak, yet the wine is clearly pinot noir despite its size and weight,” “beefy richness,” ” warm ripeness,” “suited to those who like denser wines,” “this is dense,” “extracted red,” “dense with extract,” “thick and rich,” “super ripe black cherry flavors and hard tannins,” “ it’s big,” “ big and robust,” “leathery finish ,” “ample oak flavors,” “a big, youthful pinot,” and so on and so forth. In fairness to the reviewers, there were some angelic Pinot Noirs described as “an elegant wine,” “delivers a lot of flavor without excess weight,” “this gentle pinot noir emphasizes harmony and elegance.” I have always thought of Pinot Noir as an angel - pretty, heavenly, ephemeral, and virtuous. As Matt Kramer has said, “The whole point of Pinot Noir - its very raisin d’etre, you might playfully say - is finesse. It’s what sets Pinot Noir apart from all other red grapes.” We have become a world divided on Pinot Noir: should it be a boisterous , beastly, and wild spirit, like a devil, or a shy, virtuous, and sensual being comparable to an angel? Could Cabernet be the devil in disguise, pulling the unsuspecting wine lover to the dark and evil side of Pinot Noir?

The Princess of Pinot stakes out BV |