PinotFile: 8.24 October 20, 2010

|

End of an (Imperial) Dynasty

Chinese Proverb Richard C. Wing was a distinguished and gifted Chinese-American who was extremely proud of his heritage and the unique culinary tradition he established catering to those who sought good food, good wine and good taste. His recent passing at the age of 89 years caused me to reflect on the many times I spent at the table with him, touched by his unwavering devotion to his profession and his ebullient personality. He called himself a “humble Chinese chef,” but he was highly venerated by his family and a cadre of culinary devotees alike. One has to go back to 1883 to find the origins of the Wing restaurant dynasty that lasted five generations in the San Joaquin Valley of California. The book, Becoming Chinese American: a History of Communities and Institutions (H. Mark Lai, 2004), provides some of the relevant history. Richard’s grandfather, Shu Wing Gong (known by the Anglo name of Henry Wing), was one of the many Hua Xian migrants who had fled from political persecution in China to California. He cooked for the Chinese railroad workers and opened a small noodle house restaurant known as Mee Jan Low (“Beautiful and Precious Restaurant”) in the Hanford area, before the City of Hanford existed. The restaurant was located in the central part of the block on China Alley where shops, gambling houses and opium dens were frequented by the local Chinese population. Shu Wing Gong’s son, Henry Chow Wing (also known as Henry Wing), Richard’s father, came to California in the 1920s and took over the family restaurant business when Shu Wing Gong died in 1923. The Wings had also opened the Quong Jan Low restaurant in Visalia during the 1920s, managed by cousins Howard Gong and Willie Chung Do. The Wing family also ran Wing’s Market, which has long since been renamed United Market under different ownership. Henry Wing closed Mee Jan Low in 1937 and opened the Chinese Pagoda which served traditional Chinese food such as chow mein and egg foo yung as well as Chinese banquets. The restaurant was located on the corner of China Alley and Green Street. By the 1950s, the Wing family owned all the property on the block-long China Alley except the Taoist Temple and two properties across the street from the restaurant owned by the Taoist Preservation Society.

Richard Wing began working in his family’s restaurant kitchen at the age of 6. He graduated from Visalia High School and eventually obtained a degree in architecture from the University of Southern California. His college years were interrupted by World War II. He joined the Army in 1944 and while assigned to basic training at Fort Robert in California, he was chosen by Five-Star General of the Army, George C. Marshall, to initially be his personal cook and later to accompany him to China as his Chief Aide and food taster. Richard was fluent in Chinese and well-educated, both desirable qualities for an aide. Marshall, who was allergic to shellfish and strawberries, had his own team of personal chefs that accompanied him on his trips. Richard learned cooking techniques from those chefs as well as other noted toques during his travels with Marshall throughout Asia and later in Europe. After the war, Richard spent time in a sanatorium for tuberculosis. He finished his education, returned to Hanford, and although he had no intentions of pursuing a career as a chef, agreed to help out his family with their restaurant. He never left. In 1958, he opened the Imperial Dynasty next door to the Chinese Pagoda, despite the objections of some family members who felt the restaurant and menu were too “high class.” Richard’s experiences abroad had led him to create a stylish restaurant serving a novel fusion of French and Chinese cuisines, termed chinois (also known as chinoise). The restaurant quickly became famous for its unique gourmet chinois menu, the restaurant environment itself, and the cordial Wing family members who staffed the restaurant. Sunset Magazine wrote, “Elegant food complimented by a museum-like display of Oriental art in an architectural monument - a restaurant that has become a travel destination as well as a place to eat.” The Chinese Pagoda closed in the 1970s although the neon Chinese Pagoda sign is till visible on the side of the restaurant building. It has been reported that Bing Crosby dined at the restaurant, went upstairs to the large, majestic wood-floored banquet room above the Chinese Pagoda, and sang Pennies from Heaven for the restaurant staff. Richard was the architect, contractor and decorator of his new restaurant. The walls were embellished with priceless Chinese art and artifacts obtained during his travels abroad. The unique roof of the main dining room was designed to represent the “arches of heaven.” Downstairs, a former opium den was turned into a large wine cellar and an adjacent banquet room had walls lined with jade antiquities. Richard hung the works of art himself, and cleverly placed a welcoming Buddha at the entrance to the restaurant. Richard’s brother, Ernie, was instrumental in establishing the early reputation of the Imperial Dynasty. As a knowledgeable wine buff, he was able to fill the Imperial Dynasty wine cellar with collectible California and French wines. Regrettably, Ernie died at a relatively young age, but Richard maintained the extensive wine cellar. The Imperial Dynasty was one of the first restaurant accounts for several notable Napa Valley wineries including Stony Hill, Caymus and Heitz Cellars. Richard told me that in approximately 1968, 25 cases of wine from each Domaine Romanee-Conti (DRC) vineyard were sent to the United States with 5 cases of each vineyard reaching the West Coast. The Imperial Dynasty was allocated 1 case of each vineyard and were charged initially $200 to $300 per case, increasing to $1,000 per case by 1970. On the Imperial Dynasty wine list at the time, Romanee-Conti was $200 per bottle with the other DRC wines ranging from $80 to $100 per bottle. When the Domaine raised the prices to $1,000 a case, Richard stopped buying the DRC wines as he deemed them too expensive! Nevertheless, the wine cellar grew to over 70,000 bottles and earned a Wine Spectator Grand Award. Tours of the wine cellar always preceded dinner, when many diners would search out gems to accompany their dinner. Prices were extremely reasonable by usual restaurant standards. Richard Wing was one of the creators of chinois cuisine, what he called, “French cooking with a Chinese accent.” Many people attribute the founding of chinois cooking to Austrian chef and restaurateur, Wolfgang Puck, who popularized the culinary synthesis of French and Chinese cooking at his restaurant Chinois located in Santa Monica, California. However, Wing and undoubtedly others, preceded him by a number of years. Today, Eurasian cuisine is very popular but it is difficult to successfully execute. In a paper written by Oh and Minjoo titled, “Venerable Home: Fusion Cooking and Nouvelle Cuisine,” they describe fusion cooking as follows. “In fusion cooking, everything becomes strange and familiar at the same time: the boundary between otherness and familiarity itself dissipates.” Richard’s most famous dish was Escargots à la Imperial Dynasty. People traveled from afar to Hanford just to eat this incredible version of the French classic. The Imperial Dynasty restaurant easily sold more escargot than any other restaurant in the United States. Richard was invited to cook his escargot recipe at President Ronald Reagan’s inauguration, but declined, as he was reluctant to be away from his restaurant out of loyalty to his faithful diners. The escargots was a fusion of the classical French preparation of Escargots de Bourgogne using butter, shallots, parsley, white wine and garlic with the addition of the Chinese ingredients, ginger root and cashew butter. Richard’s recipe is included below. Be careful if you try this at home! We have tried to duplicate Richard’s recipe on a few occasions with no success, setting the oven on fire during one failed effort.

Makes 6 to 8 servings as an appetizer

Sauce:

Garnish:

Snails:

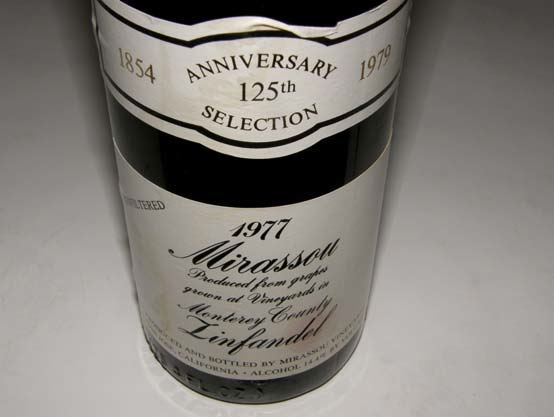

Preheat oven to 450º. Wash and clean the shells in a wire basket. Parboil the shells in boiling water with 1 tbsp baking soda. Rinse and drain. Deep fry the shells in hot peanut oil at 350º for 1 minute. Drain and sprinkle the insides of the shells with garlic salt. Place shells on a baking sheet and bake for 3 minutes. Set aside. Remove snails from the can and place in the wire basket. Lower into boiling water for 10 seconds and drain. Plunge into the hot peanut oil (350º) for 5 seconds. Drain and set aside. Heat the butter in a wok or skillet and stir-fry the garlic, shallots and ginger root. Do not brown these aromatics. Add all other ingredients for the sauce, and stir until the mixture bubbles. Add the snails, but do not let the mixture reach the boiling point. With chopsticks or a cocktail fork, stuff each snail into a shell, inserting the soft part first. Then fill each with the butter sauce and put onto small snail plates. Drape sliced onion over the top. The Imperial Dynasty had two dining areas separated by a wall. Diners could choose to eat on the “regular” side and order off the menu which offered continental cuisine and Chinese specialties. The other side of the restaurant was for those who dined by advanced reservation on the gourmet prix fixe menu. The gourmet menu consisted of six courses, accompanied by appropriate wines suggested for each course by Richard. The menu was hand-written for every table each night. When I first started going to the Imperial Dynasty in the early 1980s, the price of the gourmet dinner was a ridiculously low $40. When the restaurant closed in 2006, the price had only increased to $60. The Imperial Dynasty was always a family affair, with Richard’s sister, Harriet, managing the restaurant from the beginning. The Wing family was very close. Richard was the patriarch and Harriet was the matriarch, both providing the leadership needed to maintain the family’s close bonds. Three generations of grandmothers, mothers, sisters, aunts, uncles and cousins staffed the restaurant. Many of them had other careers during the day. Richard’s spouse, Mary, a former Miss Hong Kong, worked in the restaurant every night as a cocktail waitress. The restaurant had a long list of celebrity diners including Walt Disney who reportedly flew into the San Joaquin Valley just to eat there. Many groups traveled from the Bay Area, Fresno and Bakersfield by train to dine at the Imperial Dynasty. I loved dining there so much that I made the four-hour drive with friends to eat there about three times a year for nearly twenty years. In 1989, California Magazine wrote, “So far off the beaten path that it has to be great to still be in business. It’s not oriental, it’s gourmet. Guests from all over the world are drawn to this spot for a taste of Richard Wing’s creative genius.” Richard was also summoned to Beverly Hills on occasion to cook for famous movie personalities including Julie Andrews. Perhaps my most fond memories of Richard were the nights in which he had the energy to stay late into the night after we had finished our gourmet dinner, weaving marvelous stories of his years in the service of General George Marshall. He would often go down to the cellar, pull out a special bottle of wine, and try to stump us with its source, pouring it blindly for us with an impish grin. This was after we had eaten a six course meal and had six different wines. How could we refuse? Richard knew wine and he knew how to match wine with his cuisine, but like many of his varied talents, he always downplayed his expertise. One night he brought out a bottle of 1977 Mirassou Monterey County Zinfandel. Zinfandel was the wine upon which Mirassou’s reputation in red wine was founded. The bottle was a 125 Year Anniversary Selection celebrating the 125 years of Mirassou as a family owned winery (1854-1979). The label said that the grapes were harvested in late November and early December. The alcohol was 14.4%. I can still remember the taste of this incredible wine that was over 20 years old when we opened it. There was a fresh and rich berry nose, a full, mouth-filling taste, and a lingering finish.

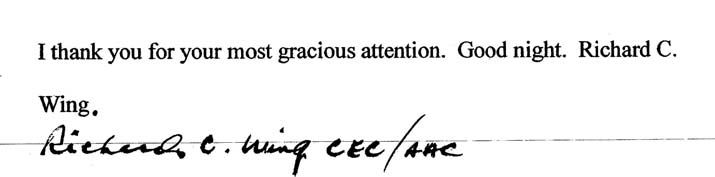

At one of my last dinners at Imperial Dynasty in 2003, Richard addressed our group by reading a speech he had prepared and delivered a few months prior (March 2003) to a group of judges who had traveled by train to the restaurant from Northern California every year for over thirty-three years. It was a heartfelt glimpse of the life of a celebrated chef who was in the twilight of his career. I was so touched by this talk, that I asked for a copy and I have included it here in its entirety for historical and general interest purposes.

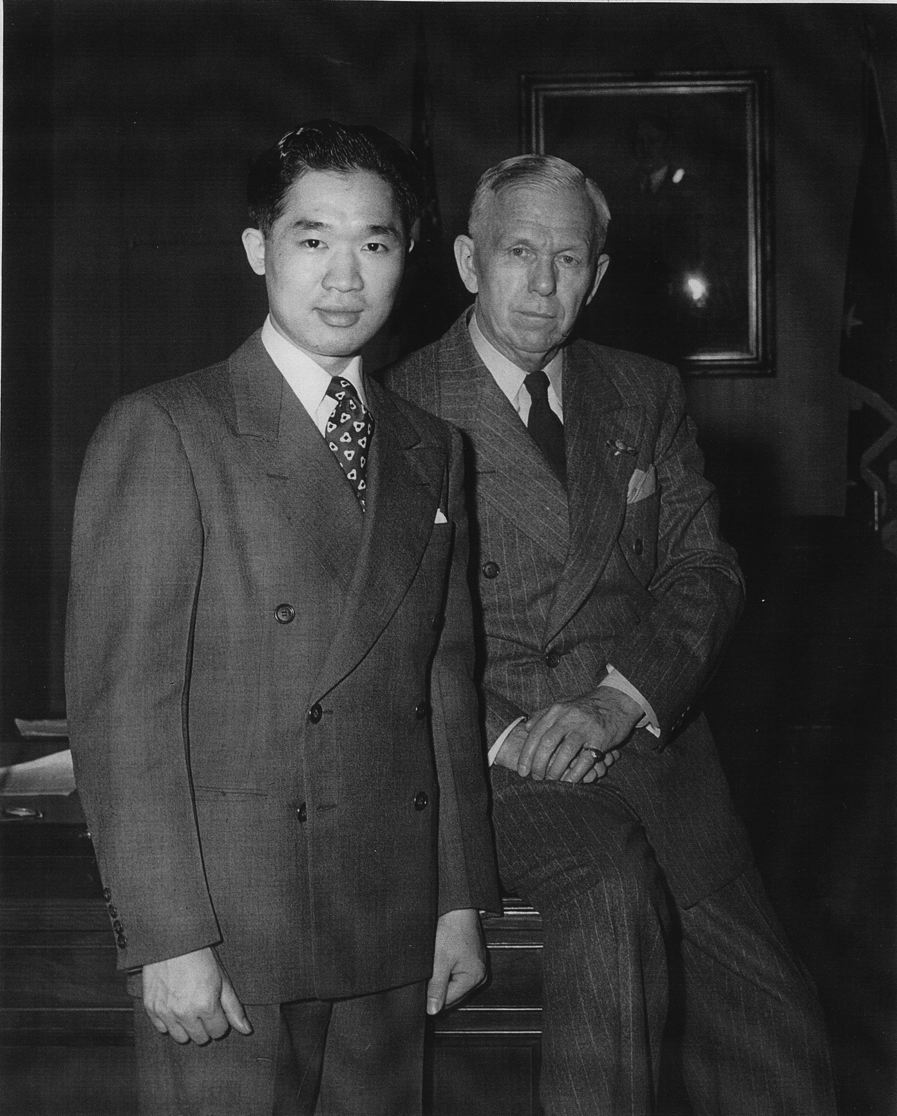

Good evening Women and Gentlemen, most honorable Judges and most sagacious attorneys, I thank you very much for being here tonight. It has always been a pleasure to cook for the Judges Dinner. I have been cooking the Judges Dinner for over 33 years at the Imperial Dynasty. The dinner was started when attorney Bob Rosson was appointed a judge in Hanford, Kings County. I am proud of my heritage and tradition in the restaurant world. I am doubly proud because we have been able to survive in this restaurant operation continuously for over 120 years in Hanford. We like to think we have established a unique culinary expression at the Imperial Dynasty. I sincerely believe that in order for a dinner to be properly appreciated, the diner, the waiter, the sommelier, and the chef should be united together in good harmony. The creation for such a harmony has been my culinary aim at the Imperial Dynasty. My grandfather, Chow Wing, was catering to the Chinese railroad workers, and decided to open a Chinese restaurant here at this location. At the time, there was no City of Hanford and no Kings County, which would come later. My good friend, attorney Bob Dowd, who is the Chairperson for tonight’s Judges Dinner, has told me he has been reading about General George C. Marshall. He would like to know more about the great General Marshall and asked me to say something about General Marshall. I accepted, and this will be the first time a humble Chinese cook talks about the greatest American general in this century. In my 82 years of living, there were three special persons who have greatly influenced by life: Professor Lo Ka-Ping, General George C. Marshall, and Professor Hans Von Koerber at the University of Southern California. Tonight, I would like to talk about the human and personal aspect of General Marshall. General George C. Marshall was the Five-Star General of the Armies and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff in World War II. After that, unexpectedly, he became the Special Envoy Extraordinary for President Truman for the China Mission. After the China Mission, unexpectedly again, he became Secretary of State. He was awarded the Nobel Peace prize for the European Recovery Program, which was called the Marshall Plan. Again, unexpectedly, he became the Secretary of Defense. General Marshall was a very great and remarkable general. Winston Churchill and President Truman both considered General Marshall the greatest American general in this century. It was in 1944 that I was in basic training for the Army at Camp Robert in San Miguel, California. One morning, a Colonel came from headquarters and interviewed me. About two weeks later, I was summoned to the headquarters at Camp Robert and introduced to a staff of officers. I was then informed that I would be leaving Camp Robert and flying to Washington D.C.. Upon my arrival in Washington D.C., a Colonel met me, drove me to Fort Myer in Arlington, and directed me to Quarter One, the official residence for the Five-Star General of the Army. I was introduced to General and Mrs. Marshall and designated to be General Marshall’s personal cook in Quarter One at Fort Myer. After 6 months at Quarter One, General Marshal retired from the Pentagon and moved to his home, Dadona Manor, in Leesburg, Virginia. General Marshall told me in a thoughtful manner that I could stay in Leesburg with them for a while, or take an early honorable discharge and return to college. I decided to stay a while in Leesburg. Within two weeks in Leesburg, I answered a surprise telephone call from the White House. It was President Truman on the line, and he wanted to speak to General Marshall. I immediately summoned General Marshall who grabbed the telephone in his study. That evening, I prepared roast leg of lamb for General and Mrs Marshall. After dinner, General Marshall casually asked me if I had been to China. I responded that I went to school in Canton for almost two years. It was during the time Japan invaded China. After that, I returned home to Hanford, California, where I was born. General Marshall asked me if I still had relatives in Canton. I replied that most of my relatives were living in a village located 18 miles from Canton. My ancestral family had 21 acres of rice paddies and a large spreading residential estate over an acre in the village. Then General Marshall said, “You will be going to China with me in about a month from now. In the meantime, you will be briefed and trained by experts and specialists in security, protocol and food tasting. As you know, I am allergic to shellfish. Afterward, you will be my personal aide and food taster in China.” I was overwhelmed by such an assignment. It was like a fantastic dream for me. Imagine a humble Chinese cook being offered this wonderful privilege to be assigned to the great Five-Star General for the China Mission. In late December 1945, we departed from Washington D.C. for mainland China. Our first stop was in California where Frank McCarthy, an assistant to General Marshall in World War II, greeted him. On arrival in Shanghai, General Wedemeyer and Walter Robertson were there to greet General Marshall. After a few days in Shanghai, we flew to Chungking, the wartime capital for Generalissimo Chiang Kai-Shek’s Party. A large group of Chinese officials were there to greet General Marshall. We were in Chungking for over seven months and then moved to Nanking, the official capital. After several months in Nanking, General Marshall decided to return to Washington D.C. to report to President Truman on the China Mission. General Marshall then went home to Leesburg to join Mrs. Marshall. It was a happy time at Dadona Manor. After a short time in Leesburg, General Marshall had to leave for his second trip to China. Fortunately, this time, Mrs. Marshall decided to be with General Marshall on the China Mission. General Marshall stopped over in Tokyo, Japan to visit General Douglas Mac Arthur. We had a delightful luncheon at the very spacious home of General Mac Arthur. The beautiful home was surrounded by a magnificently landscaped garden. After the luncheon, I went outdoors to stroll leisurely and marvel at the beautiful surroundings. While I was momentarily in awe in the garden, I felt someone behind me tapping on my shoulder. I turned around, and with great surprise, came face to face with General Douglas Mac Arthur in person without his corncob pipe. Instead he was holding a package. General MacArthur spoke directly at me and said, “Just a while ago in the house, General Marshall has told me you will be going to Canton very soon. Will you take this package with you to Canton? This package belongs to Amah, to be delivered to her family in Canton.” I replied, “Yes sir, General, I will be glad to do so.” Then General MacArthur boldly interjected, “Splendid, I appreciate your instant and prompt response to agree to help Amah.” Afterward, General MacArthur introduced me to Amah who was born in Canton. We talked to each other in Cantonese dialect and were very much at ease. On the same day, we departed Tokyo on a flight to China. While on the flight, General Marshall instructed me, “Next week, you will be going to Canton to visit your relatives, and you will carry out General Mac Arthur’s mission in Canton. Everything will be properly arranged for your trip to Canton.” On my arrival in Canton, I was very surprised to see Major Henry Ching, who was born in Hanford and lived in Fresno. He was employed by the California State Agriculture Department. I immediately handed over Amah’s package to Henry Ching who was the proper receiver. He mentioned to me that in recent days at the U.S. Army Headquarters in Shamen, Canton, the staff was stirred up because of two unexpected messages, which were related to me. One message was from the Office of General MacArthur in Tokyo and one message was from the Office of General Marshall in Nanking. Both messages indicated the proposal to take care of me in Canton. Imagine, two great Five-Star Generals were concerned about my well being in Canton! I drove a jeep to the village to visit my relatives and joyfully gave away my duffle bag full of goodies which contained candies, cookies, nuts, chewing gum, soaps, shampoos and dried fruits. After four days of fun and pleasure in Canton, I returned to Nanking. In 1946, summertime was very hot in Nanking. Generalissimo and Party had decided to move to Kuling, Lushan and make it the summer capital. Meanwhile, Premier Chou En-lai and Party would be in Nanking. In order for General Marshall to negotiate with the two Parties, he had to divide the week’s schedule accordingly. To travel to Kuling, Lushan, a mountain retreat, one had to use mountain paths suitable for walking or be carried on a sedan-chair. There was no proper road for cars. Along the paths, there were seven tea stops. Normally it took about 1.5 hours to reach Kuling. General Marshall made seven trips to Kuling from Nanking in the summer of 1946. General Marshall and staff stayed in Kuling at the Pleasant House, part of the compound quarters for Generalissimo’s group. The house had a large veranda which was an outdoor place for evening movies. The seating arrangement in the veranda was carefully planned. The first and second rows had two sofa chairs in each row and was reserved exclusively for General and Mrs. Marshall and Generalissimo and Madame Chiang Kai-shek. The following rows consisted of dining chairs for seating staff members. The outside of the house was surrounded by beautiful gardens. In the afternoons, the three great ladies, Madame Chiang Kai-shek Madame Wei Tao-min, and Mrs. Marshall got together for tea and friendly chats. One morning while in Kuling, General Marshall ordered me to take the day off and told me that Madame Wei had invited me over to her house. On my arrival, Madame Wei welcomed me and escorted me to the dining room for breakfast. She then introduced me to Ambassador Wei Tao-min and a her niece, a very lovely girl whose name was Jenny. I was seated next to Jenny. I was impressed by her as she was friendly, charming, personable, sophisticated, well-educated, very pretty, and from a high ranking family. I had a suspicious feeling that lovely Jenny was supposed to be my pending date. After a good breakfast, we went on a picnic tour on sedan-chairs. We toured many interesting and lovely places located among the natural beauty of Lushan. There were two servants along with the tour. After a while, a picnic luncheon was ready for us to enjoy. After the picnic tour, we returned to the house. Later on in the early evening, an elaborate dinner was served, and after dinner, Madame Wei intentionally suggested that I must take Jenny to the movie. Normally the movie would start at 8:00 p.m. when it became dark outside. We were walking to the veranda very slowly, hoping that the movie had already started in darkness. When we arrived, the movie had not yet begun as they were waiting for our arrival. Imagine how I was feeling in that moment of dilemma! Immediately after our arrival, both Madame Chiang Kai-shek and Mrs. Marshall got up from their front row seats to offer their comfortable sofa chairs for Jenny and me. At the same time, Generalissimo and General Marshall both stood up to offer their seats to the ladies. The two gentle ladies graciously declined the gallant offer, and seated themselves in the third row in high straight back dining chairs. I was petrified and speechless during the bewildering happenings. I was numb, unable to watch, and had no idea about the movie. When the movie was over, somehow I was able and pretentiously bold enough to escort Jenny home, with everybody watching Jenny and myself clumsily leaving the veranda. The following morning when I was with General Marshall, he carefully questioned me, “Did you enjoy last night’s movie? You and Jenny were very nice together. How do you feel about Jenny?” I replied with straightforwardness, “Sir, I just don’t know how to answer. I cannot remember anything about the movie because I was too nervous. I was seated in the front row with a lovely girl next to me. I had no right to be in the front row. It was just not proper for me to do so. When the two great ladies offered their reserved seats, I should have declined, because the situation was strictly protocol forbidden. I awkwardly slouched down on the sofa chair, and tried hopelessly to hide in my embarrassment. I was stunned, bewildered, and hopelessly helpless. It was a moment of ridiculous protocol confusion. Jenny is a very lovely girl from a high-class family. However, I fear that I am no match for her. I become frightened even to dare to think of the possibility. The real truth is that lovely Jenny is just too good and too high class for me. I am not ready, because I still have to complete my college education, and besides, I am just a cook.” That afternoon, as usual, the three great ladies were together in the beautiful garden enjoying tea. Somehow, they had received the message that lovely Jenny was too good and too high class for Wing. When General Marshall became the new Secretary of State, he was scheduled to the Big Four Foreign Ministers Conference in Moscow at the end of February 1947. The United States delegation consisted of the Secretary of State and top military and political advisers on European and Russian affairs. The delegation consisted of General Mark Clark, the military Governor of Austria, General Lucious Clay, the military Governor of the United States occupied zone of Germany, General Bedell Smith, the United States Ambassador to Russia, Charles Bohlen, an expert in German and Russian affairs, Robert Murphy, an expert on European affairs, Benjamin Cohen, an adviser on Russian affairs in the State Department, and Harrison Freeman Matthews, an expert on European affairs. In Moscow, we stayed at the Spaso House, a large stately mansion home for the United States Ambassador General Bedell Smith and Mrs. Bedell Smith. During that time in February 1947, the weather in Moscow was extremely cold (40 degrees below zero) and I was sick in bed with the flu for a week. Mrs. Bedell Smith invited us to the ballet at the famous Bolshoi Theater. Secretary of State Marshall did not attend because he was being briefed by the delegation on the following day’s meeting with the Russian Foreign Office. Six of us attended the ballet at the Bolshoi including Mrs. Bedell Smith, General Mark Clark, General Lucious Clay, Robert Murphy, John Foster Dulles, and me, Richard Wing. We were seated in an exclusive box seat. The ballet for the evening was Tschaikovsky’s Swan Lake, featuring the celebrated and legendary prima donna, Ulanova, the greatest ballerina in Russian ballet. It was a breathtaking performance of perfection, an unforgettable and enchanting evening at the Bolshoi. The following morning, I told General Marshall about the magnificent ballet as it seemed that he was interested to hear my remarks about the evening. When General Marshall was meeting with the delegation, he casually asked General Mark Clark about the previous night’s ballet at the Bolshoi. General Mark Clark mentioned that the ballet was about some kind of feathered birds dancing and tip toeing all over the stage, and he said the ballet was called “Goose Pond!” All of a sudden, there was an outburst of contagious laughter from the distinguished delegation. The entire room was amused over “Goose Pond.” General Mark Clark thought it was humorous as well, saying that the goose-stepping ballet was really “funny and goosey.” General Mark Clark highly recommended to General Marshall that he see the unforgettable and “goosey Goose Pond.” In the Spaso House, my bedroom was adjacent the telecommunications room. One evening, I noticed a group of staff members had gathered next to the telecommunications room. I was curious and asked a staff member what was happening. I was told that they were waiting to sign their names and home telephone numbers on a list that would allow them to telephone home to the United States. The cost was $2.00 for 5 minutes. This diplomatic courtesy was for that day only and only one call per person was allowed. Imagine, a transcontinental telephone call from Moscow to your hometown anywhere in the United States for only $2.00 for 5 minutes. I signed my name and telephone number on the list and waited for my proper time connection. My brother, Ernie, answered the phone in Hanford. He was surprised and excited to hear from me from Moscow. My sister Harriet took over the phone. She was even more excited and worried, and kept asking all kinds of questions about my health and why I would call from Moscow. By the time I was able to talk over the telephone, I was only able to say ten words, and it was over. One morning in August 1947, a month before my honorable discharge from military service, I received a surprise telephone call from General Carter at the Office of the Secretary of State. He told me that I had an appointment with the Secretary of State at 11:00 a.m. that morning. I replied, “You must be joking with me. I was with General Marshall all morning until he left in his limousine to return to the State Department, and that was less than an hour ago. Besides, you know that I live with General and Mrs. Marshall at 2500 Foxhall Road.” With a jovial tone of voice, General Carter strong commanded me, “Just be ready, Rudolph will come by and pick you up.” With a confused and bewildered feeling I went to see Mrs. Marshall. I told her about my official appointment with the Secretary of State and she said smilingly, “You just go with Rudolph to the State Department and see what will happen.” When I arrived at the State Department, General Carter was pleased to see me and directed me to the Office of the Secretary of State. At the same time, Dean Acheson, Under Secretary of State, and Robert Lovett, Assistant to the Secretary of State, were coming out of the Office of the Secretary of State. As I entered the Office, General Marshall was busy at his desk. He signaled and summoned me to stand beside him. James Shepley came in with a camera. He was a photojournalist in Washington D.C. for Time magazine. James Shepley later became the Editor in Chief for Time. He took more than a dozen photos from various angles of General Marshall and myself. Later on, Shepley processed, developed and selected four photographs for General Marshall’s approval. On the following day, General Carter presented the four photographs to me. All four photos had been personally autographed by General Marshall. I was overwhelmed and deeply touched with joyful delights.

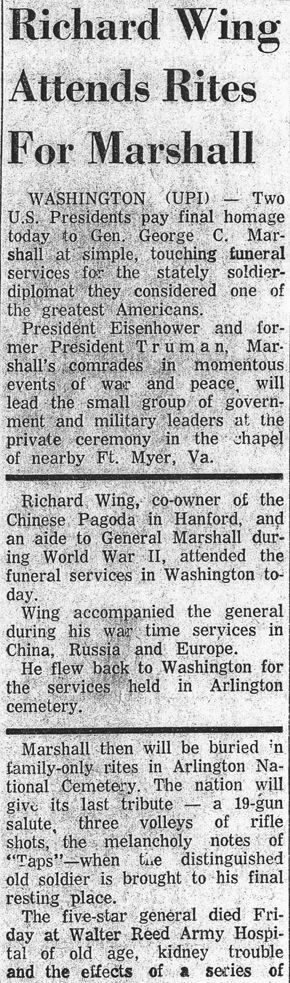

General Carter informed me that in all of his years of service as an assistant to General Marshall, it was the only time, by official appointment on the agenda, that General Marshall ever offered such a memorable gift to a person. I was speechless. (Note: General Marshall shunned publicity and there are precious few remaining photographs of this great man). That evening, I expressed my sincere gratitude to General and Mrs. Marshall for their precious photo gift of kindness and for their gracious kindheartedness. I will forever and always be in tune with the reflection of a life long memory of the privilege and honor to serve General and Mrs. Marshall, two magnificent people. In October 1959 I received a telegram from Colonel George who was an aide to General Marshall. The message asked that I attend General Marshall’s funeral ceremony in Arlington Cemetery. General Marshall had left instructions for his own funeral. He said, “Bury me simply, like any ordinary officer of the United States Army who has served his country honorably. No fuss. No elaborate ceremonials. Keep the service short. Confine the guest list to the family, and above everything, do it quietly.”

The Chapel in Arlington Cemetery was rather small, seating less than 200 people. On one side of the center aisle, Mrs. Marshall was seated in the first row and the family members were seated in the rows behind. On the other side of the aisle, President Eisenhower was seated in the first row and former President Truman in the second row. I came with General Carter and Forrest Pogue, a military historian, and we were seated in the eighth row. The ceremony was brief, simple, quiet and emotionally touching as if we were all spiritually touched by General Marshall. As we were leaving through the center aisle in the Chapel, there was a strange mystical and heavenly feeling that General Marshall had arisen to eternity. It was the passing of a very great, even extraordinary man, and yet, one who was so simple and humble. It was my final visit with General Marshall, who has transcended to a higher and peaceful place beyond the world of conflicts. I am at home now in my kitchen in Hanford, California.

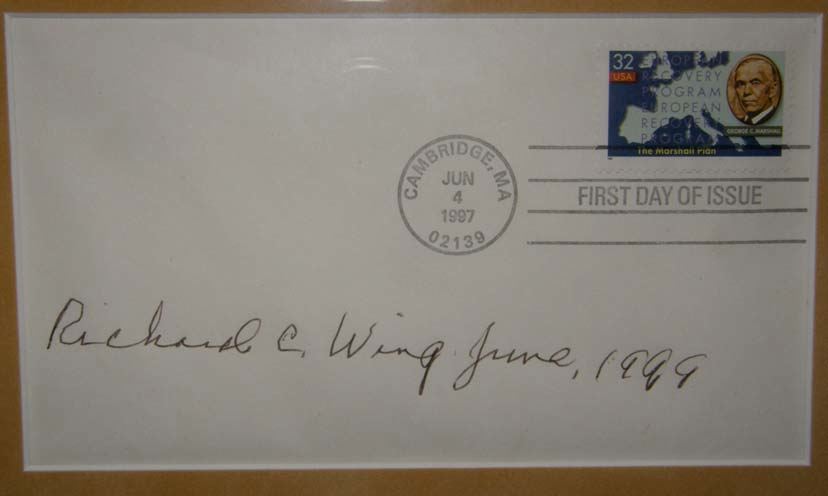

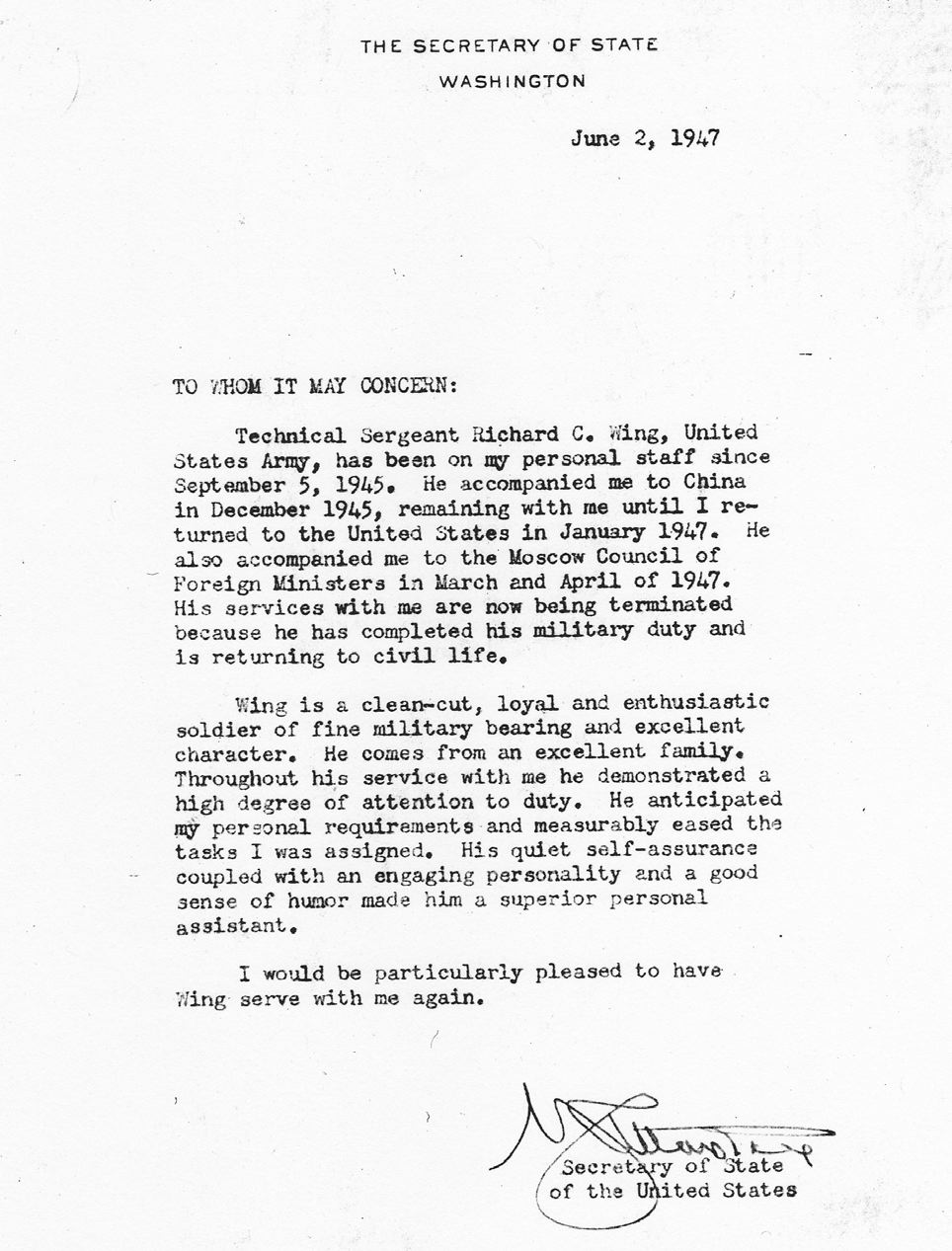

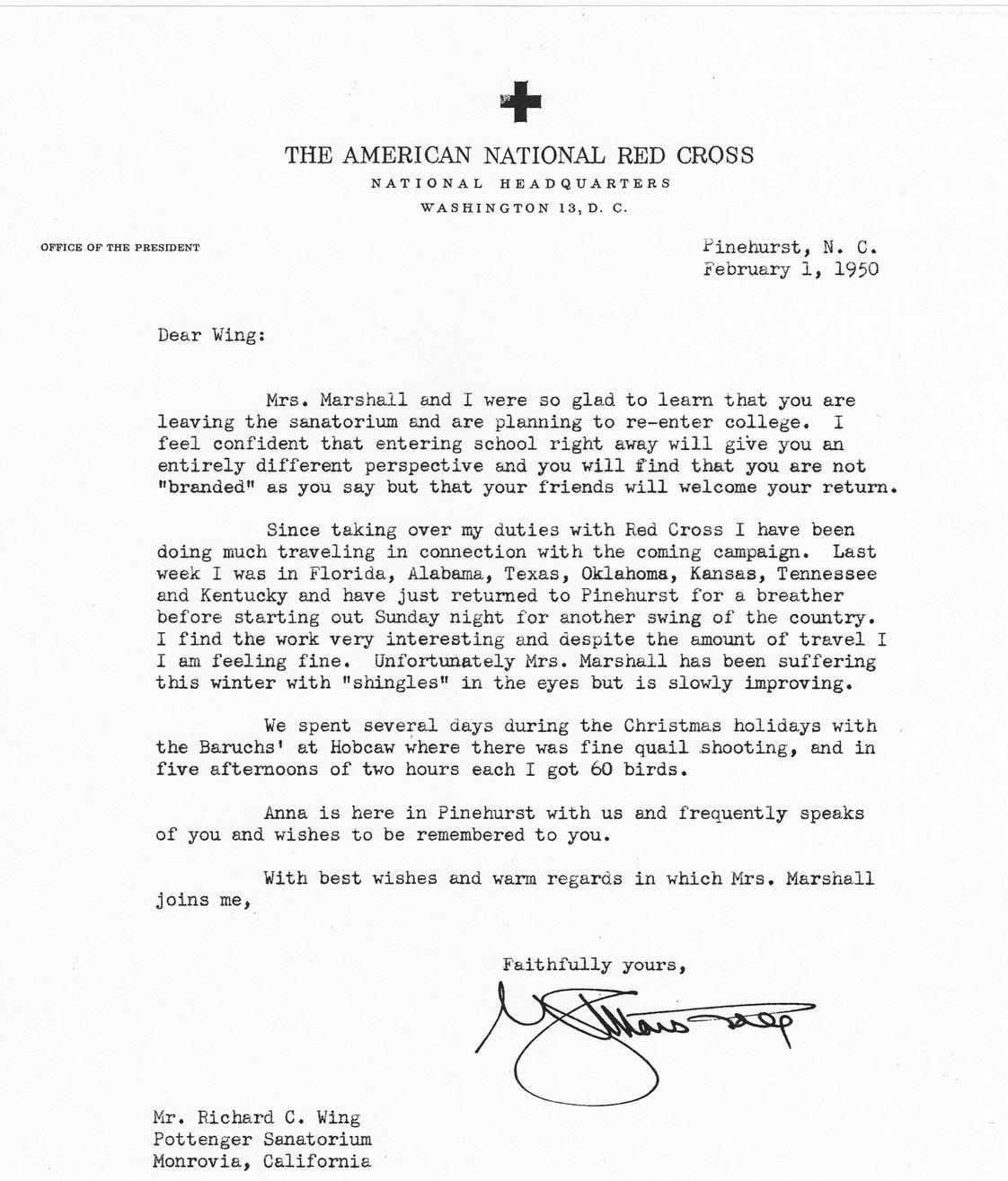

Below is a first-day of issue envelope honoring General Marshall’s European Recovery Program. It was signed for me by Richard in 1999. I have also included two letters and an additional photograph: one is a letter of recommendation from General Marshall given to Richard Wing after his honorable discharge from the Army and the second is a very personal letter sent to Richard when he was recovering from tuberculosis. The photograph shows a young Richard Wing with General Marshall.

|