PinotFile: 8.39 June 10, 2011

|

Oregon Pinot Noir: Who Planted First?

There is ambiguity, as well, surrounding the birthplace of Pinot Noir in Oregon and in Oregon’s heartland of Pinot Noir, the Willamette Valley. A brouhaha erupted last year when the economic development committee of Forest Grove, Oregon, in an attempt to attract business and tourists, adopted the slogan, “Forest Grove: Where Oregon pinot was born.” The claim is displayed on the Forest Grove website: www.forestgrove-or.gov/visitors/ wine-country-getaways.html).

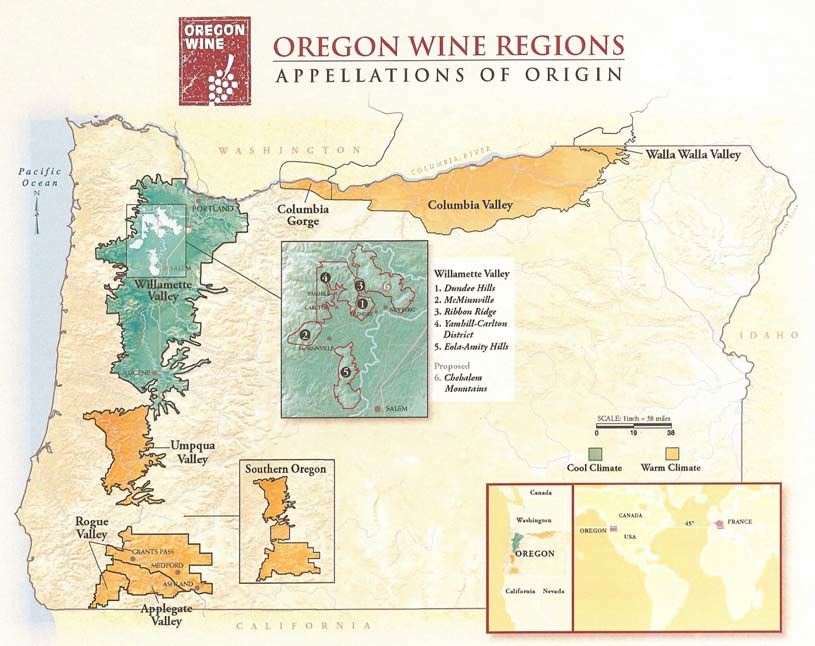

Forest Grove, located 35 miles south of Portland in the Willamette Valley, is currently the home to twelve notable Oregon wineries including Adea Wine Company, Elk Cove Vineyards, Patton Valley Vineyards and Tualatin Estate Vineyards. Among a list of “Forest Grove Firsts” on the City of Forest Grove website (www.forestgrove-or.gov) is the claim, “Pinot Noir was first planted in a Willamette Valley vineyard by Charles Coury in 1965 at the present-day David Hill Vineyard.” In the website’s Wine Legacy Information Sheet, Forest Grove asserts, “The original idea that Willamette Valley would be ideal for the production of Pinot came from Charles Coury, who purchased the vineyard now known as David Hill Winery on September 30, 1965. Coury immediately began planting his vineyard in October 1965.” The Wine Legacy Information Sheet incorrectly details the first plantings of Pinot Noir in the Willamette Valley and unfairly and incorrectly relegates David Lett’s historical role to secondary status behind Coury. In addition, the Wine Legacy Information Sheet fails to recognize the first planting of Pinot Noir in Oregon by Richard Sommer at HillCrest Vineyard in the Umpqua Valley, although Forest Grove officials have in recent months orally acknowledged Sommer’s contributions to Oregon wine history. This misinformation has caused consternation and even outrage among the folks in the Umpqua Valley of Oregon who are jealous of their history and rightly claim that their region is the birthplace of Pinot Noir in Oregon. Lett’s family, as well, has been dismayed, since they can provide documentation that the first plantings of Pinot Noir in the Willamette Valley, long considered the heartland of Oregon Pinot Noir, should be attributed to David Lett. The lineage of Oregon Pinot Noir has been plagued through the years by misguided and unintentionally inaccurate oral histories, along with misinformation and misunderstanding in the wine literature. To provide credible clarification and documentation, I interviewed Dyson DeMara, who assumed ownership of HillCrest Vineyards from Richard Sommer in 2003, and Phil Gale, Sommer’s long time vineyard manager and assistant winemaker. Unfortunately, a significant portion of Sommer’s personal records were destroyed after his passing, and the remaining material has yet to be catalogued. I also enlisted David Lett’s son, Jason Lett, the current proprietor, winemaker and vineyardist of The Eyrie Vineyards in the Willamette Valley, and David Lett’s spouse, Diana. They were able to provide archival documentation of David Lett’s legacy. My research will show that although Forest Grove and its favorite son, Charles Coury, played an important role in Oregon Pinot Noir history, Forest Grove is not the birthplace of Pinot Noir in Oregon or the Willamette Valley. To begin, I will review what we know, what we have been led to believe, and what has been widely reported in the press and literature over the last fifty years regarding the modern era of plantings of Pinot Noir in Oregon. I will present new information corroborated by first-hand knowledge obtained through interviews and supported by archival documentation. After a brief overview of pre-Prohibition winegrowing in Oregon, I have split the main discussion into two parts; the first details the earliest modern era (post-Prohibition) history of Pinot Noir in the Umpqua Valley and the second, the modern era history of Pinot Noir in the Willamette Valley. There is no documented evidence of Pinot Noir vines in Southern Oregon or the Willamette Valley in the 19th or early 20th century, although it is well known that Oregon winegrowing and winemaking predated Prohibition. A good amount of pre-Prohibition research has not been vetted properly, but the following information has been published. Paul Pintarich in The Boys Up North (1997) credits Henderson Luellen with planting Oregon’s first wine grapes in 1847 in the Willamette Valley. The first commercial vintner in Oregon Territory was probably Peter Britt, a well-known photographer of the time, as detailed by Lance Sparks in Eugene Magazine (winter 2008). Sparks culled the journals, records and photo plates of Peter Britt preserved by the Southern Oregon Historical Society and concluded that Britt planted his first vineyard adjacent his house overlooking Jacksonville in what is now the Applegate Valley AVA of the Rogue Valley of southern Oregon. He pressed his first wine from Valley View Vineyard in 1858, and received recognition for his wines from local newspapers by 1866. Britt later acquired more land and planted two major vineyards called The Farm and The Ranch. He obtained cuttings from California missions, traveling salespersons and mail order. An undated note from Britt’s writings reveals that he bought Grosser Blauer, Bourchet Hybrids, Gamay, Johannesburg Riesling, Black Burgundy, Trousseau, Mataro, Gutedel and Malbeck. He may have eventually planted more than 200 varieties of wine grapes. Britt sold his wines to neighbors and to the Catholic Church for altar wine. An 1889 exhibition of wine at the California State Viticultural Commission meeting lists one of Britt’s wines as ‘Burgundy.’ Whether this wine was made from Pinot Noir grapes will probably never be known. The book, Photographer of a Frontier: The Photographs of Peter Britt, is currently out of print but is in the libraries of the Oregon Historical Society in Portland and the Southern Oregon Historical Society in Medford. Several German immigrant vintners including Edward and John Von Pessi and Adam Doerner planted wine grapes and made wine in southern Oregon by the 1880s. Ernest Reuter established a reputation for Klevner (a Germanic term for Pinot Blanc) in the Willamette Valley in the 1880s, made from grapes grown on Wine Hill, west of Forest Grove, the eventual site of Charles Coury Vineyards, and today, the David Hill Winery. The wine industry in Oregon was devastated by 1919 due to the Temperance Movement and Prohibition.

Umpqua Valley, OregonH. Bruce Smith, who writes the blog, Umpqua Valley AVA News (www.umpquavalley.blogspot.com) has offered some information about Richard Sommer, which has also been widely reiterated in the wine press. Smith has created the website, www.forestgroveoregonpinotenvy.com to refute Forest Grove’s claims. Although DeMara and Gale offered me invaluable verification of Sommer’s achievements, it is important to first review what has been written about Richard Sommer in the most plausible wine literature over the last twenty-five years. Richard Sommer is widely considered the founder of Oregon’s modern wine industry. Growing up, he made wine at home and attended University of California Davis, graduating with a degree in agronomy, and later studying range management at University of California Berkeley. According to Paul Pintarich in The Boys Up North (1997), Richard Sommer left California in the late 1950s to establish HillCrest Vineyard on the site of a 40-acre old egg farm in the Upper Valley of the Umpqua, northwest of Roseburg. Adolph Doerner, whose family planted wine grapes in the Umpqua Valley in 1888, assisted Sommer with the first plantings. Sommer was particularly interested in seeking out an appropriate climate for White Riesling and Pinot Noir. Before settling at HillCrest, he had conducted detailed studies of the weather in areas of the Umpqua Valley where table grapes were being grown successfully. Roseburg stood out because it had the requisite amount of sun to ripen grapes, possessed enough coolness to prolong the growing season, presented minimal threat of frost, and had well-drained soils. Sommer first planted grape vines in the Umpqua Valley of Oregon at HillCrest (also appears as Hillcrest) Vineyard in 1961, the first post-Prohibition Vitis vinifera planted in Oregon. The original HillCrest plantings were put in the ground in 1961, 1962, 1963, 1964 and 1968, and included Pinot Noir among the reportedly 35 grape varieties planted there.

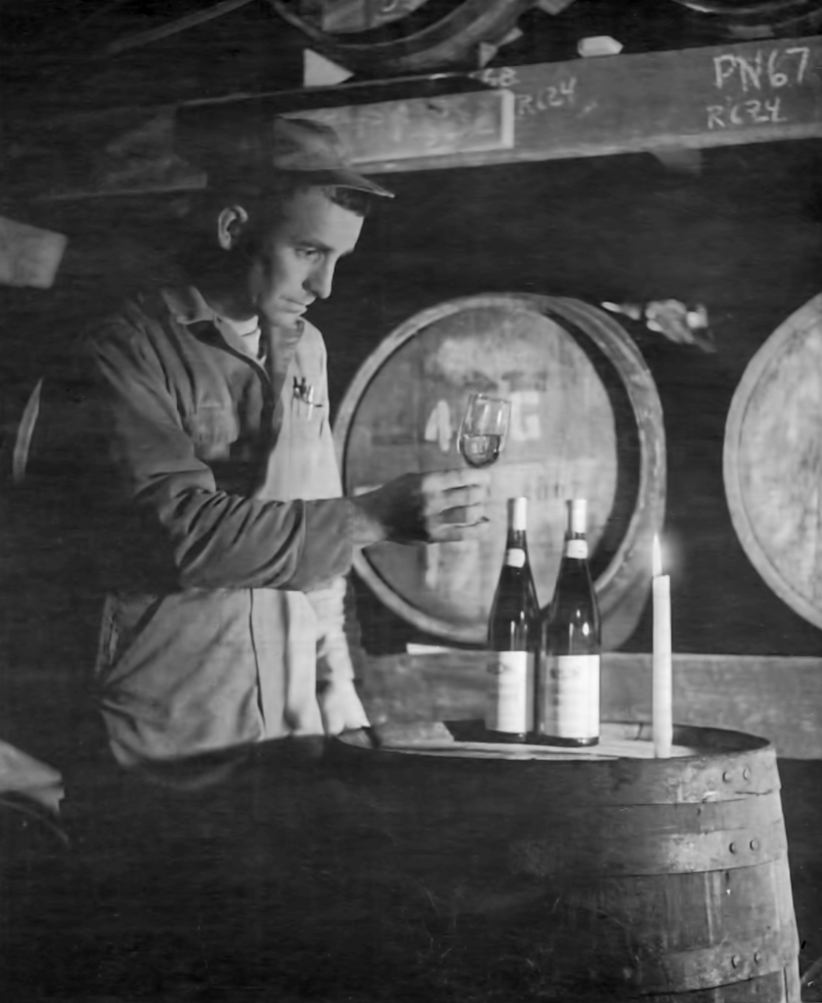

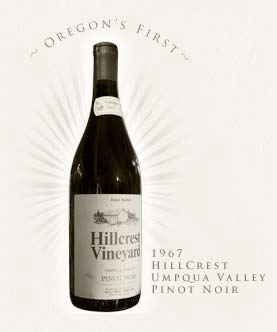

Sommer also acknowledged the potential for wine grape growing, and in particular Pinot Noir, in the Willamette Valley to the north, and he referred to the wine pioneers who arrived in the late 1960s and early 1970s as “the boys up north.” Dick Erath, who was a classmate of Sommer’s in a course at the University of California Davis in 1967, credits Sommer for encouraging him to move to the Willamette Valley. It has been reported that David Lett and Charles Coury visited Sommer at HillCrest Vineyard before establishing their vineyards in the Willamette Valley, but according to Diana Lett (David Lett’s surviving spouse), neither Lett nor Coury knew about Sommer before moving to the Willamette Valley. Sommer has been portrayed in the literature as an iconoclast, described as brilliant by many, but decried as a loner and eccentric by others. Some have called him “erratic, stubborn, quirky and a little weird.” More favorable impressions have also been forthcoming, including “energetic, with a subtle wit, and a keen sense of observation.” He loved nature and the outdoors and devoted himself so fully to that passion, he had no time for marriage and children. According to the book, Vineyard Memoirs (2004), written by Kerry McDaniel Boenisch, a Douglas County Public Meeting was held in 1971 with the topic, “Prospects of a Grape and Wine Industry for Oregon.” Charles Coury, David Lett, Dick Erath, Ray Doerner and Richard Sommer were in attendance. Sommer reportedly said, “Here in Roseburg we have a perfect climate for growing certain types of wine grapes such as White Riesling, Chardonnay, Cabernet Sauvignon and Pinot Noir. I moved to Roseburg in 1960 and in 1961 I planted 4 acres of eight varieties of wine grapes. I was in full production in 1966, making 6,000 gallons of wine. In 1961 I started with a mother block of eight varieties including Gewürztraminer, Chardonnay, Cabernet Sauvignon, Sauvignon Blanc, White Riesling and Pinot Noir.” Anthony Dias Blue (American Wine: A comprehensive guide, 1988), stated that Sommers planted initially in 1961, using cuttings from the Napa Valley he brought to Oregon from California, and “moved to a rustic beadand- bat winery and expanded his vineyard to include Cabernet Sauvignon and Pinot Noir in 1963.” However, one source, The Winemakers of the Pacific Northwest (1977), states, “Sommer planted Pinot Noir from the beginning.” The HillCrest Vineyard winery was bonded in 1963 (Oregon Bonded Winery 44), the same year Sommer released his first wine, a Riesling. We know he had commercially bottled a Pinot Noir-labeled varietal wine as early as 1967. Dyson DeMara still has some bottles in his possession as shown in the photo below. This was a first for Oregon, and preceded the first Pinot Noir released by David Lett in 1970 at The Eyrie Vineyard (labeled “Spring Wine”) and the first Pinot Noir commercially produced by Charles Coury at Charles Coury Vineyards (although the exact date is undetermined, it was certainly after 1967).

I asked noted Pinot Noir scholar, John Winthrop Haeger, who wrote both North American Pinot Noir (2004) and Pacific Pinot Noir (2008), to weigh in on the birthplace of Pinot Noir in Oregon since his published writings have focused on the Willamette Valley of Oregon and do not reference Richard Sommer. Here is his response. “I think it is accepted fact that Sommer planted Oregon’s first Pinot Noir in modern times, at Hillcrest, in 1961. We know for certain that his first vines went into the ground in 1961, and we ‘think’ Pinot Noir was among the varieties he planted in the first go, but he was white variety-oriented, so I suppose it is possible that Pinot Noir was not planted until a year or two later.” Even Charles Coury, who was not known for his modesty, acknowledged that Sommer preceded him to Oregon, and is quoted in Vineyard Memoirs by his sister-in-law, Betts Coury, as admitting, “He (Coury) was the second person to make a decent wine in Oregon behind Richard Sommer.” With that as background, the following historical information was relayed to me by Phil Gale, many details of which were independently corroborating and embellished by Dyson DeMara. This proved to be invaluable information, since little documented information about Richard Sommer appears in the wine literature. Phil Gale grew up tending orchards in Southern California. This background served him well, although he had no training in viticulture when Sommer hired him in 1975. Gale met Sommer in 1970 while he was working in a local mill and journeyed to Sommer’s vineyard to buy wine. Sommer became his mentor, teaching him vineyard management and winemaking, and Gale was to become a devoted friend who worked for Sommer for thirteen years, eventually becoming the vineyard manager and assistant winemaker at HillCrest Vineyard. Their relationship was not always sublime, and Gale, who admits to being bullheaded, regrets responsiblity for being fired at least a dozen times. In every instance, however, Sommer would call him the following day asking, “When are you coming back to work?” Gale grew to revere Sommer, and when we spoke, Gale became quite emotional to the point of tears while reminiscing about Sommer and his many accomplishments. Gale emphasized to me over and over, “Everyone absolutely loved the guy. I never heard anyone say anything negative about him.” Gale described him as gentle, generous and extremely respected by the Douglas County community in Umpqua Valley. Although admittedly eccentric (in a good way), and Bohemian, he was a prominent, admired figure whom the locals counted on for wine at a time when there were precious few other sources in that small southern Oregon locale. Neighbors would flock to HillCrest Vineyard at the end of the growing season, reveling in the harvest and participating in the picking of the grapes. Many would make regular visits throughout the year to buy wine as well. Sommer was of German-Swiss heritage and his father was a scientist. His mother was from Ashland, Oregon, located at the southern end of the Rogue Valley, and his grandfather had a vineyard there. His grandfather’s success gave Sommer confidence that winegrowing could be successful in southern Oregon. Sommer graduated from the University of California Davis in 1957 and upon arriving in Oregon, worked in the Douglas County assessor’s office. Sommer first established his vineyard in 1961 with cuttings obtained in 1959 from Louis Martini’s Stanly Ranch Vineyard in Carneros, California. The only grape variety not obtained from Carneros was Zinfandel that had proved itself in the local vineyards of Ray Doerner and was obtained from the Doerner property. The original vines were rooted in 1960 in the Winston area of the Umpqua Valley and transplanted by Sommer to his property in 1961, the same year he assumed title of the 40-acre ex-egg farm near Roseburg in Douglas County. The property was owned by the Conns, former area land aristocrats of the 1800s who lived on the site. Because of the varied climates and complex mix of landscapes of the region, the Umpqua Valley (see map below) proved to be suitable for growing both cool and warm climate grape varieties. When Sommer arrived, there was no significant history of winegrowing to draw on, except the successful plantings of Ray Doerner (whose family started Oregon Bonded Winery 7) and a few others nearby. As a result, Sommer planted numerous varieties of Vitis vinifera as well as seeded and seedless table grapes, seeking to find grapes that could thrive at his site. DeMara recalls that 35 varieties were planted at HillCrest Vineyard. Gale emphasized, however, that Sommer was focused most specifically on Riesling and Pinot Noir, harboring a special love for the latter. The marketplace demanded that he rely more on Riesling initially, because there was little interest at the time in Pinot Noir as a distinct varietal.

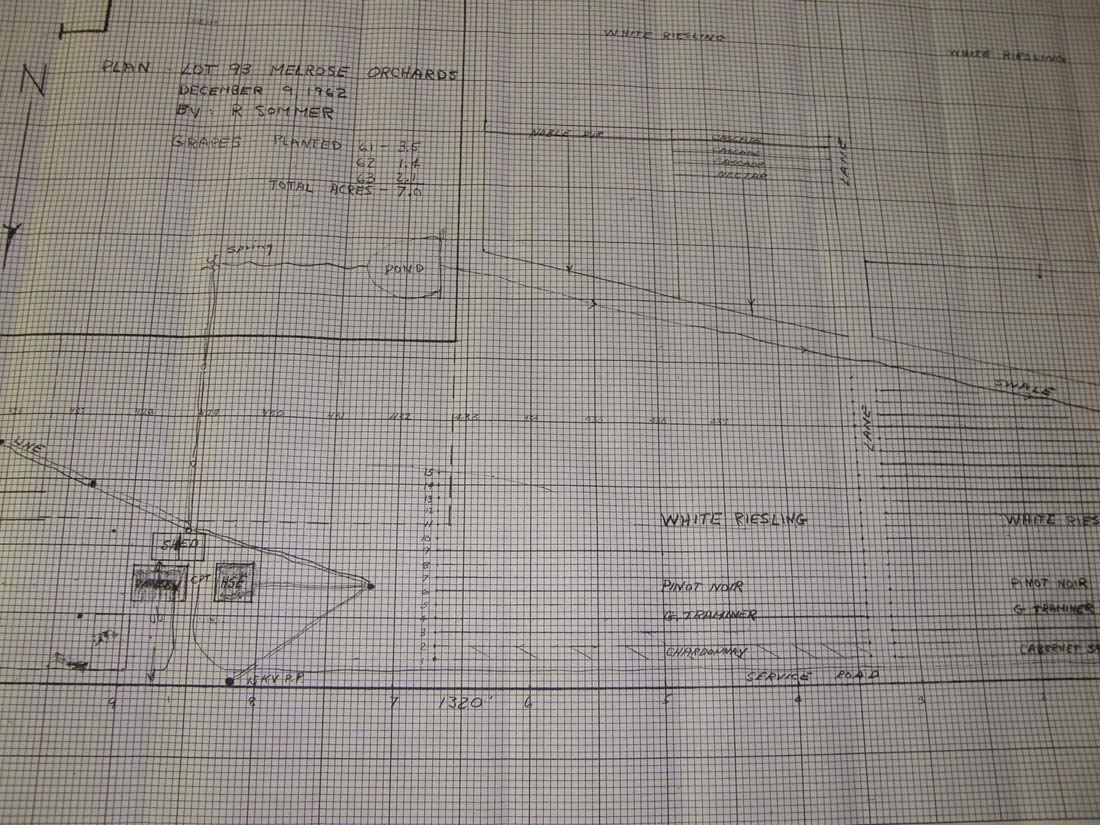

Sommer chose a plateau on his property at an elevation of 850 to 900 feet to plant his first vineyard. There was a good layer of topsoil down 3 to 4 feet underlain with sandstone. Gale’s recollection and Sommer’s master planting map from 1962 supplied to me by DeMara (see below) indicate that in 1961 Sommer planted a total of 3.5 acres, consisting primarily of White Riesling, Chardonnay, Cabernet Sauvignon, Gewürztraminer, and Pinot Noir (rows 5,6,7 and 8 in the vineyard). There were 50 vines in a half row, making the initial plantings of Pinot Noir about 400 vines. All the Pinot Noir was Pommard clone. Trellising was Geneva Double Curtain. Additional White Riesling was planted in 1962 (1.4 acres) and 1963 (2.1 acres), bringing the total vineyard acreage to 7 acres by the end of 1963. Further plantings of Pinot Noir and White Riesling and tiny amounts of other varieties (including Semillon, Sylvaner, Sauvignon Blanc, Malbec and Gamay Noir) followed in 1964 and 1968, all in larger blocks than in the first plantings. The 1964 plantings were established in an area north of the original vines in what had been known as the Fraun Vineyards after the German who had previously owned that land. DeMara notes that the 1968 plantings of Pinot Noir vines which included UCD 18 selection, are the oldest remaining Pinot Noir vines on the property, and included UCD 18 selection, some of which remain. Pinot Noir was also planted, managed and sourced by Sommer on adjacent properties owned by others including Vern Anderson who bequeathed his vineyard to Sommer upon his death in the late 1970s. Sommer eventually farmed a total of 50 acres of vineyards at HillCrest Vineyard. Sommer’s farming was organic minded, but fungicides were employed out of necessity when sulfur spraying proved inadequate in some vintages. The vines were dry farmed, enabled by the adequate rainfall in the area (Gale recalls as much as 35 inches a year). Rain was always a threat at the end of the growing season, but Douglas County often benefited from a couple weeks of Indian summer that propelled the ripening process. Although forty or so neighbors picked the grapes at harvest in the early years, Sommer eventually employed a small well-trained crew of workers to perform the task. Conifers were planted on the property on lower ground that rose up to the bench where the grapes were established. For years, Sommer sold the conifers as “you cut” trees at Christmas to supplement his income. One of the biggest challenges to farming grapes at HillCrest Vineyard was the ravenous birds who had a special liking for Pinot Noir. A number of defenses were used including 12-gauge shotguns, propane cannons and taste deterrents. In 1975, Sommer came up with the idea of using radio-controlled airplanes painted to simulate hawks. This turned out to be a very effective deterrent. Netting was finally employed despite its added cost to the the additional labor required and the expense of the nets. Gale cleverly devised a method of fusing the individual rows of nets, creating a circus-style tent over multiple rows.

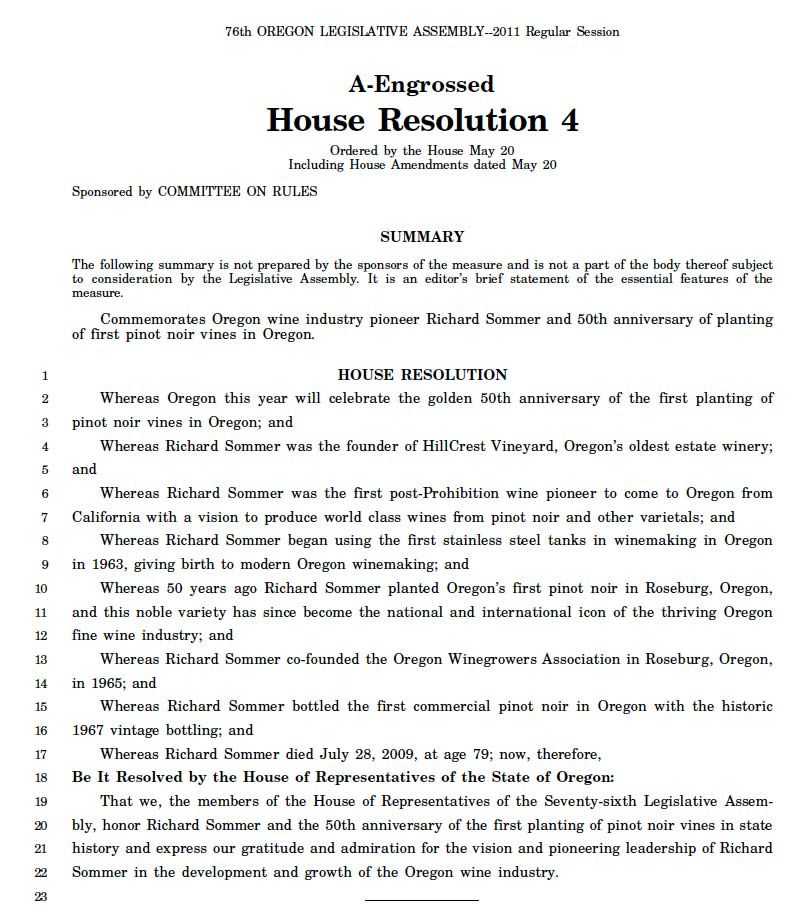

Sommer was a rather diminutive figure patrolling his vineyards, only 5’6” in height, and often wore a signature beret and blue coveralls. Gale notes that Sommer had almost a “Buddhist reverence for nature.” He always kept a notebook with him and chronicled his every vineyard activity in detail. He was an inveterate note-keeper and his pockets were always filled with his writings. He was also obsessed with weather monitoring including measuring the sun’s radiation, and his weather acumen bestowed on him a “sixth sense” of when to pick his grapes. DeMara still has many boxes of climate records from Sommer’s past. Sommer was also frugal. During one vintage, the crew was bottling splits and Sommer insisted on cutting the corks in half, doubling their usefulness! He refused to buy any equipment to replace what he could repair himself, not only to save money, but because he truly loved old equipment and enjoyed tinkering, repairing, and jury-rigging it. For example, Gale recalls his fashioning a wooden worm gear for the bottling line. The first commercial HillCrest wine, a Riesling, was released in 1963, and the first commercial Pinot Noir came in 1967. DeMara reported that a visitor to Sommer’s house recalled seeing and being served bottled Pinot Noir from as early as 1963, while Gale dates the first Pinot Noir to 1964. In the formative years, Pinot Noir was blended with some Gamay. There was little market for Pinot Noir at the time and most of Sommer’s early success was built on a blend of Riesling and Cabernet Sauvignon vinified with residual sugar and named Mellow Red that was sold in gallon and half-gallon jugs. Other red blends, Umpqua Red and Dago Red, were also produced for a short time. Early on, elderberry wine was also a component of Mellow Red, but this was stopped after wine authorities discovered the practice. Mellow Red was still in production when DeMara acquired the property in 2003. Sommer’s HillCrest Vineyard Pinot Noirs were inconsistent, often a victim of the vintage climatic vagaries. The 1970, 1978 and 1979 wines benefited from warm weather and these Pinot Noirs were said to be “amazing” by Gale. There was little recognition for the wines within Oregon, but the distributor for HillCrest wines raved about them publicly. Gale was emphatic to me in his praise of Sommer’s Pinot Noirs, but admitted that the wines were “spotty” in some vintages. Sommer has been credited in the literature with being the first in Oregon to put the name of a grape variety on the label of his wines, but this is inaccurate and there were others who preceded him. Botryitis was not unusual in Sommer’s vineyards, and in 1978 he crafted Oregon’s first modern era ice wine. He also produced sparkling wine at HillCrest Vineyard. Interestingly, Sommer’s wines were fermented in a cement pit, bucketed into a press and raised in barrels. In the case of Riesling, whiskey barrels were used, imparting an unusual flavor to the wines. The Riesling was styled in a Moselle fashion with high acidity (0.9 g/100 ml) and some residual sugar (2.5 g/l). With Pinot Noir, grapes were usually de-stemmed, but occasionally whole clusters were crushed or added back for added astringency. Although punch downs were used, Sommer also employed a technique in which the cap was allowed to drop on its own, up to three weeks after the initiation of fermentation. Called flavonoid reduction, this extended maceration produced high tannins, but when the cap dropped, the tannins would soften appreciably. The grapes were usually picked at 23º to 24º Brix. Typically, an alcohol level of 13% was achieved, sometimes with the benefit of added sugar. Elevage of Pinot Noir took place primarily in French oak barrels, with some Oregon oak barrels included. Although initially Sommer worked with very rudimentary winemaking equipment, he had the resourcefulness to repair it when it broke. Until 1965, his winery was housed in a former tiny egg storage room. In 1975, a 10,000 square-foot winery was built on the property, and the egg storage room became a wine library vault. Gale, who helped built the winery, fondly recalls sitting in the rafters of the partially built winery at lunchtime with the construction supervisor, Bud Anderson, and enjoying Sommer’s wines. The Willamette Valley had a market for Sommer’s wines, but tiny Roseburg (about 11,000 people at the time) could not support HillCrest as it expanded. Production in 1966 of 6,000 gallons had reached 30,000 gallons by 1987 with Riesling and Pinot Noir being the biggest sellers, and Sommer turned to a distributor to move the wines into markets outside of the Umpqua Valley. Sommer had a business sense and originated the idea of wineries offering barrel tasting tours to attract consumers. Dyson DeMara took over HillCrest Vineyard in 2003. He had met Sommer in 1999 and spent time with him both before and after assuming control of the winery. Regretfully, Sommer’s sister consigned many of Sommer’s records to trash after the winery was sold. She has kept boxes of undeveloped photographic film that Sommer, who was an avid photographer, had accumulated. Some records remain in DeMara’s possession, but DeMara has not had the time to thoroughly research them. When the winery was sold in 2003, much of the original plantings were dead, primarily from the fungus, Eutypa lata (Eutypa dieback disease). DeMara pulled out most of the original 1961 plantings in 2004, including all the Pinot Noir (he retained a few removed Pinot Noir plants for archival purposes), leaving some Chardonnay, Riesling and Sylvaner. Of the original vines rooted in 1961, 1962, 1963, 1964 and 1968, 13 acres remain at HillCrest Vineyard, primarily consisting of the 1964 plantings. Sommer never sought out recognition for his remarkable career, leading several writers and friends to remark over the years that he had not received the acknowledgement he deserved. He never exhibited any malice to those who found him eccentric. Toward the end of his career, he was a bit remorseful, saying, “I regret that I never tooted my own horn.” Sommer passed away July 28, 2009, at the age of 79. A memorial was held in his honor on September 27, 2009. The Letts were unable to attend but Diana wrote DeMara and offered her condolences, “My husband David always enjoyed his friendship with Richard, stretching over 40 years, and we respected Richard’s position as the first person in Oregon to grow Pinot Noir. Although I visited with him only a few times over all the years we shared as ‘Oregon Wine-Folks,’ I will remember Richard with affection and respect.” Largely due to the efforts of Dyson DeMara and others, Sommer has finally received the long-overdue recognition he deserves. A House Resolution ordered on May 20, 2011, by the 76th Oregon Legislative Assembly, commemorates both Oregon wine industry pioneer Richard Sommer and the 50th anniversary of the planting of the first Pinot Noir vines in Oregon. A copy of the resolution follows.

Richard Sommer is held in high regard by the Umpqua River Valley community and has received a prominent place in the Douglas County Museum of Natural & Cultural History in Roseburg. For those with curiosity, the Museum is currently offering an exhibit titled “Wine: A 10,000 Year History,” which traces wine from its earliest roots in the Middle East to the Umpqua River Valley, “America’s last great undiscovered wine region.” Certainly, “undiscovered” is an apropos description of Richard Sommer’s contributions to Oregon’s rich wine history. Visitors are welcome at HillCrest Vineyard where one can view bottles of Oregon’s first Pinot Noir and see Pinot Noir vines dating to 1968. Look in on the website at www.hillcrestvineyard.com. to see HillCrest’s current wine offerings and to plan a visit.

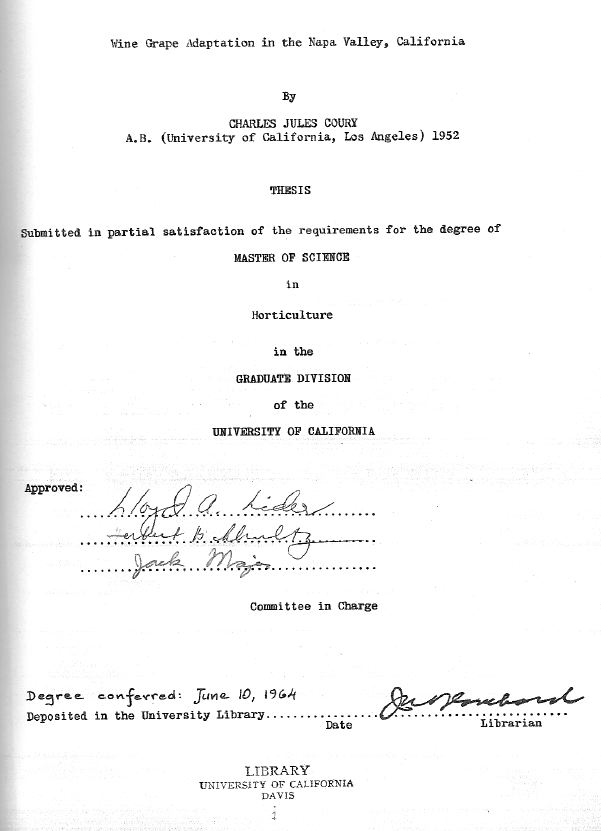

Willamette Valley, OregonThe truth regarding the first Pinot Noir plantings in modern times in the Willamette Valley has been confusing, with both Charles Coury and David Lett given that attribution depending on the information source. John Winthrop Haeger told me the following. “According to Leon Adams (The Wines of America, 1978), Lett planted his first vines in 1965, Coury his in 1966. However, David Lett told me that his first vines were planted at Eyrie in 1966. (He did not tell me, by the way, that he had pre-planted vines at Corvallis, but that’s a plausible story.) Other sources hold that both Coury and Lett planted in 1965. Coury and Lett came to market the same year, and the first vintage for both was probably 1970. Certainly 1970 is the correct date for Lett, although he did not label his first vintage of Pinot Noir as Pinot Noir, but as ‘Spring Wine.’” [My comment: many published sources cite Coury’s first commercial releases as from the 1970 vintage, but it is unclear when he released his first Pinot Noir for sale.] “Planting in 1965 or 1966 and harvesting a first commercial crop 4 or 5 years later sounds pretty reasonable for the time and circumstances. I trust Adams generally, but he did not work from primary documentary evidence. Mostly he interviewed the principals. It’s very common that dates are garbled in oral histories - unintentionally. I’d say the only way to sort out whether Lett or Coury both planted during calendar year 1965, or both in calendar year 1966, or one a year earlier than the other, is to compare contemporaneous documents for both enterprises.” Noted wine writer Leon Adams (The Wines of America, 1985 - 3rd Ed) stated, “In 1965 Lett planted the valley’s first Vinifera vineyard to be started in five decades.” Thomas Pinney (A History of Wine in America, 2005) credits Coury with being the first of the modern Willamette Valley pioneers. He declared, “ Coury’s thesis concluded that the Willamette Valley would be a place where grapes adapted to northern European regions - Burgundy and Alsace - might flourish.” An often-quoted reference by Lisa Shara Hall, author of Wines of the Pacific Northwest (2001), states that Charles Coury left California for Oregon in 1965 and planted “a wide range of Alsatian varieties - including Pinot Noir,” but she does not set a specific date for Coury’s first plantings. Hall dates the Oregon Pinot Noir era from 1965, when she says David Lett first rooted Pinot Noir cuttings near Corvallis, beginning the transplanting of these vines to the Dundee Hills at The Eyrie Vineyard in 1966. The Forest Grove website claims that Charles Coury purchased his 45-acre farmstead in Forest Grove at the current site of the David Hill Winery on September 30, 1965, and “immediately began planting his vineyard in October 1965.” (However, this is an unlikely scenario since vineyards are traditionally planted in the spring. Most likely, he started a nursery on the site.) The website states that David Lett established his Dundee Hills vineyard in the spring of 1966. One piece of information that has positioned Coury in the forefront chronologically is the words of Betts Coury, Charles’ sister-in-law, who along with Coury’s spouse, Shirley, helped Charles establish his winery. In the book, Vineyard Memoirs, written by Kerry McDaniel Boenisch, Betts Coury quotes Charles as saying, “Sommers is the original pioneer, not me. I was the second. Before Lett, before Fuller, and before Erath. I graduated way ahead of those guys. Heck, they all read my thesis at Davis on cold-climate growing and argued with me about whether it could be done successfully in Oregon. The reason I moved to Oregon in 1965 was to prove that excellent Burgundian and Alsatian wine grapes could be grown there.” It is important to point out that Boenisch did not interview David Lett for her book, and her and Betts Coury’s accounts were mostly taken from Charles Coury directly, or second hand, from others. A recent interview with Dick Erath, who arrived in the Willamette Valley in 1967 and knew both Lett and Coury, was conducted by Karl Klooster and published in the Oregon Wine Press (March 2011). Erath stated that Coury bought Reuter’s property in Forest Grove in a foreclosure, started working on the deal in 1964 and moved there in early 1965. (This statement is confusing since it is known Charles and Shirley Coury were in Europe throughout 1964 and did not move to Oregon until the latter part of 1965). When asked who first planted Pinot Noir in the Willamette Valley, he said, “As far as I know, 1965 was the year and, since spring is planting time, I’m assuming they both planted then. The difference is that David planted nursery rows (babies to be used for propagation) and Coury put in rooted vines.” When pressed to verify the claim of Forest Grove (and vis à vis Coury) about being the first place where Pinot Noir was planted in the Willamette Valley, Erath begged the answer. Perhaps the best-researched and most current information about David Lett was offered by Mark Savage, MW (The World of Fine Wine, Issue 22, 2008) in a tribute after Lett’s passing on October 9, 2008. He notes, “In 1965, at the age of 25, by now convinced that Oregon’s Willamette Valley offered the best hope for Pinot Noir in America, he made his move to Oregon ‘with 3,000 cuttings and a theory,’ and planted the cuttings in a rented nursery plot while he went looking for the perfect vineyard site in which to pursue his passion.” He goes on to say, “...in 1966 he and his new spouse Diana planted the 3,000 cuttings at The Eyrie Vineyard.” Savage credits Lett with being “the first person to plant Vitis vinifera in the Willamette Valley.” How to make sense out of all this conflicting information? Fortunately, David Lett’s son, Jason Lett, and David Lett’s spouse, Diana, have chronicled David’s winegrowing career in the Willamette Valley with extensive documentation and they agreed to share their knowledge and some of their invaluable archival material with me. The following represents the facts based on their contributions, my research, and various reliable reference sources including the book, The Winemakers of the Pacific Northwest (1977). David Lett grew up on a farm in Utah, graduated from the University of Utah in 1961, and was in San Francisco waiting to begin dental school when a road trip to Napa Valley wine country led to a life-changing epiphany. He enrolled instead in a two year viticulture course at University of California Davis. After graduating in 1964, he traveled to Europe, and spent almost a year visiting northern Europe, including Burgundy, talking to vintners, winegrowers and viticulture professors about cool climate viticulture. Charles Coury, who grew up in Oregon, obtained a degree in climatology from the University of California at Los Angeles and was well versed in agricultural growing seasons. For a period, he sold imported European wines for Jules Wile, then entered the University of California Davis where he was a classmate of Lett’s and where he obtained a Masters of Science degree in Enology, graduating in June 1964. He too, would travel to Europe after graduation, studying cool climate viticulture and clonal adaptation at INRA (National Institute for Agronomy Research) in Alsace, France. Both Lett and Coury found Northwestern Oregon an appealing location for growing cool climate grape varieties despite the sentiment at Davis that Oregon was not suitable for the successful cultivation of European wine grapes. Harold Berg, Lett’s Professor, told Lett that there were very few climates suitable for Pinot Noir in the United States. Vintners in California had been working with Pinot Noir for years with little success and the prevailing opinion was that it was just too hot in California for Pinot Noir. Oregon had some glimmer of potential for both Vitis labrusca and Vitis vinifera and several research vineyards were planted in Oregon by the late 1950s. It has been reported in the literature that Charles Coury proposed the theory that Vitis vinifera produces the best quality wines when ripened at the limit of its growing season. Coury considered the growing season in Northwestern Oregon to be an opportune place to support his hypothesis and, as a result, he has been widely credited with the idea of pursuing winegrowing and in particular, Pinot Noir cultivation, in the Willamette Valley. However, Lett should be given equal recognition, for in his commitment to finding a cool climate to cultivate Pinot Noir, he kept coming back to Oregon, thinking its climate and growing season was the closest to Burgundy of any other known alternatives in the United States. A recent review of the archives in the University of California at Davis library reveals that the only thesis that Coury wrote and published at Davis was titled, “Wine grape adaptation in the Napa Valley, California.” Although Coury’s thesis, published in 1964, had no reference to Oregon, Coury did delineate the relationship between climate and suitable grape choices. He wrote, “Any variety yields its highest quality wines when grown in such a region that the maturation of the variety coincides with the end of the growing season.” An abstract of the thesis is available at www.wineserver.ucdavis.edu/thesis/detail.php?id27. A copy of the title page of the thesis is included below.

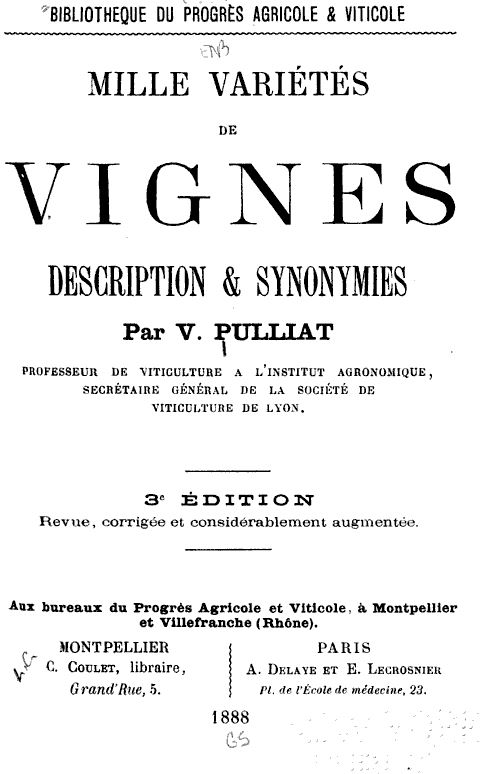

The Forest Grove Economic Development Commission’s chairperson, Don Jones claims he conducted research to indicate that Coury’s thesis “proposed that the Willamette Valley would be ideal for Pinot Noir,” and incorrectly asserts that, “without him (Coury), our beloved wine pioneers wouldn’t have known to come to the Willamette Valley” (NewbergGraphic.com, December 22, 2010). Jones did admit that technically, by about eight to twelve months, Lett was the first to plant in the Willamette Valley in Corvallis, but unfortunately chose to downplay the important distinction. The notion of matching wine grapes to climate was not hatched by Coury or Lett, or their Davis faculty predecessors, for it originated in the writings of Jules Guyot and Victor Pulliat in France in the 1800s. The idea was researched in this country by noted American viticulturist, Albert J. Winkler, Professor of Viticulture in the department at Davis in the mid-1900s. Together with his student and later colleague, Maynard Amerine, also a professor at Davis, Winkler devised a heat summation system for grapes. The number of “degree days” of sunshine an area received was quantified allowing growers to determine which grape was best suited to a particular growing region. The degree days were determined by the length in days of the growing season and the average daily temperature above 50ºF. The growing regions were classified from I (the coolest) to V (the warmest). The scale was first published in 1944 and updated in 1963, and remains a standard directive for grape growers in matching grape varieties to appropriate geographic areas. From handwritten notes taken at University of California Davis, Lett clearly studied closely the writings of Victor Pulliat (1827-1896) a French ampelographer, who took his inspiration from Dr. Jules Guyot (1807-1872). Guyot was a French physician and agronomist who is best known for his work in viticulture. L’ institut universitaire de la Vigne et de Vin (Institute Jules Guyot) at the University of Burgundy in Dijon is named in his honor. He introduced the Guyot system of cane pruning of vines for trellises. Victor Pulliat, born in Chinobles in the Beaujolais region of France, was a student of botany, and in particular, grape vines. In 1869, he started the Regional Society for Vinegrowing and recommended grafting on resistant roots from America to renew French vineyards devastated by phylloxera. He published Le Vignoble with Alphonse Mas (an apple tree specialist) in three volumes between 1874 and 1879. This treatise contained descriptions of 228 grape varieties. Pulliat further wrote Mille Varieties de Vignes, Description and Synonymies (A Thousand Varieties of Vines, Descriptions and Synonyms) in 1888, in which he described a grape maturity classification system used worldwide by ampelographers. In the book, he quoted Guyot, who had contributed to his inspiration for this system:

“It is with good reason that Dr. Guyot formulated this principle by saying that, ‘The major

problem to be solved for our various regions is to find the variety of vine best suited to a given

soil and climate.’”

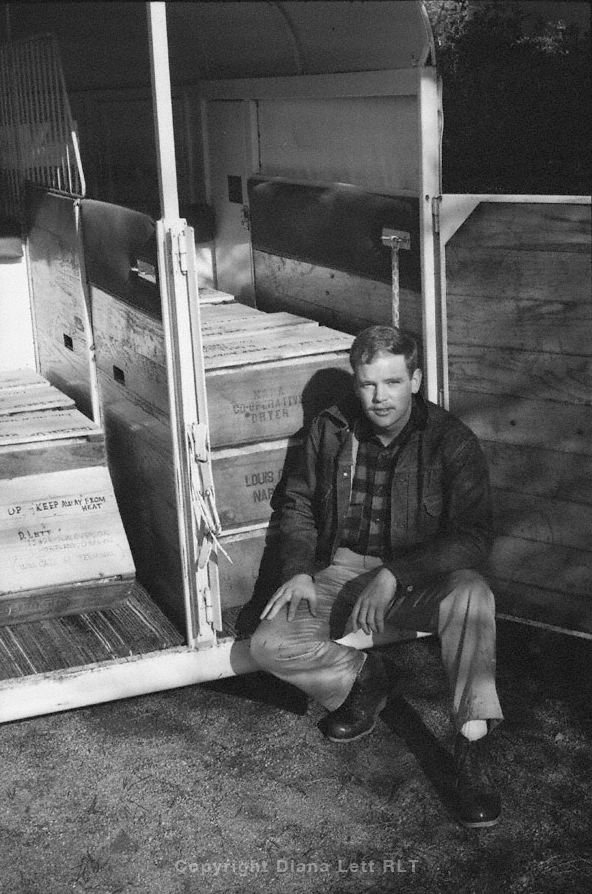

“If this problem has been solved for many of our renowned vineyards, there are many who are still far from obtaining their maximum yield and quality due to lack of cultivation of vine varieties well suited to the climatic conditions where they must live.” Pulliat classified the principal Vitis vinifera grape varieties into five groups according to the order in which they ripened in comparison to the Chasseles grape (Chasseles is the benchmark grape by which the dates of maturity of the other grapes are compared). Lett applied the principles of ripening date classification outlined by Pulliat in his choice of plantings for the Willamette Valley of Oregon. Mary Boyle (The Quarterly Review of Wines, summer 1996) quotes Lett, “After my year of studying Burgundian varieties in France, I was sure the marginal climate of the Willamette Valley was the perfect place to cultivate them in the United States.” Period I grapes had the best chance of being successfully grown in the climate of the Willamette Valley and included Pinot Noir, Pinot Gris, Pinot Meunier, Muscat Ottonel, true Pinot Blanc and Chardonnay. Lett also added Riesling, which although a Period II grape, developed flavors early and could be picked slightly underripe. When Lett, at the tender age of 25, returned to the United States in the fall of 1964, he gathered 3,000 mostly certified grape cuttings from University of California Davis and other sources. Armed with several thousand cuttings, Lett traveled to the Willamette Valley and started a nursery just outside Corvallis in February of 1965 where he planted several cool- climate Period I grape varieties including Chardonnay, Pinot Gris, Pinot Meunier, and Pinot Noir ( Wädenswil - 1A and Tout Droit - UCD 18) and Period II Riesling. The vines were planted in rows to root while he looked for an ideal vineyard site in the Willamette Valley. The photo below shows a young David Lett before departing for Oregon in early February of 1965 with a trailer full of vine cuttings packed in wooden wine boxes.

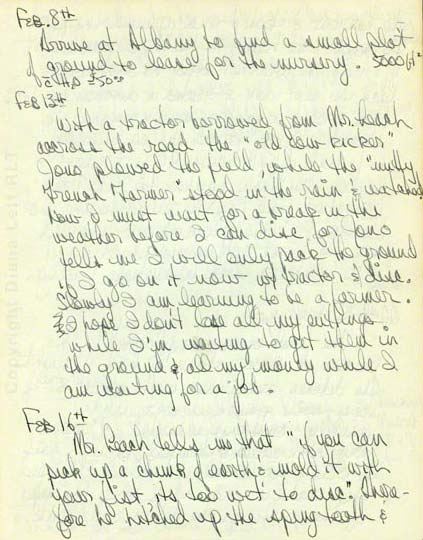

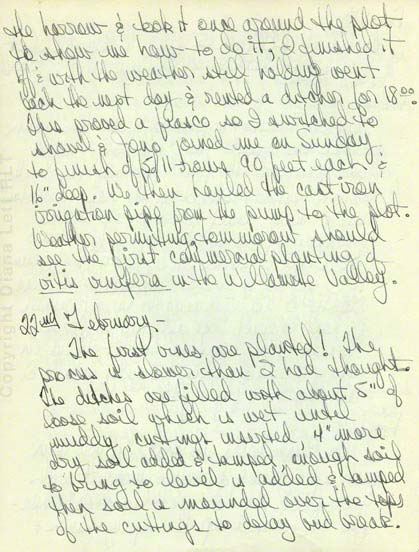

An entry from David Lett’s personal journal pictured below indicates Lett found a suitable site to lease for his plantings in Corvallis on February 8, 1965. Lett borrowed a tractor to plow nursery rows for the Willamette Valley’s first Pinot Noir vines on February 13, 1965. A photograph below shows the vineyard being plowed on that date. In the journal, Lett reveals his concerns: “Slowly I am learning to be a farmer. I hope I don’t lose all my cuttings while I’m waiting to get them in the ground and all my money while I am waiting for a job.”

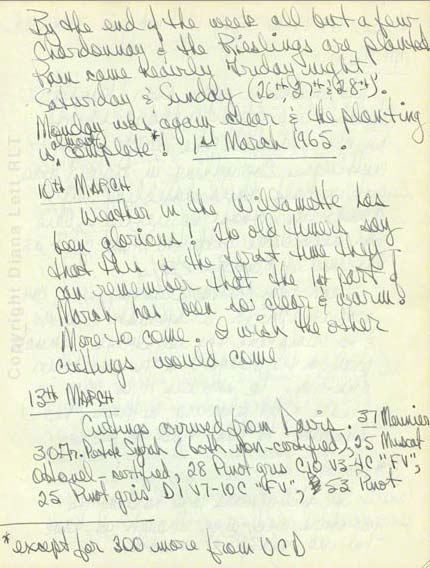

Lett’s subsequent journal entry indicates the first planting of Vitis vinifera (including Pinot Noir) in the Willamette Valley took place on February 22, 1965.

An additional journal entry by David Lett indicates that planting was complete on March 1, 1965.

A photograph shows David Lett christening the first planting in the Willamette Valley in the spring of 1965.

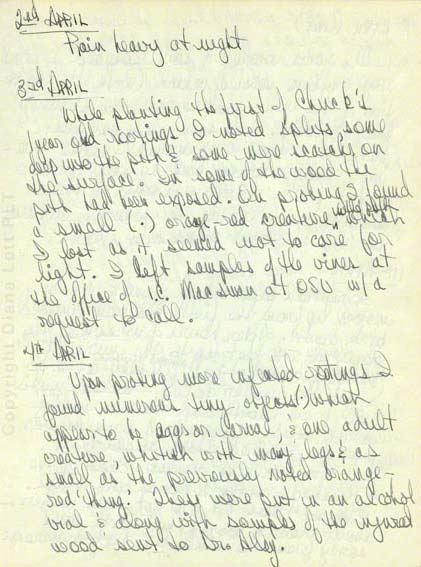

In the first half of 1965, the Courys were still living in California, visiting Oregon at intervals to look for vineyard land. Lett’s journal indicates that on April 3, 1965, Lett planted some one-year-old cuttings for the Courys in his Corvallis nursery, sent to Lett from California.

A photograph from June 1965 below shows Lett’s plantings in Corvallis. Note the mix of cast iron and aluminum irrigation pipe and Lett’s hand tiller in the background.

David Lett subsequently located his original vines to his ideal vineyard site in the Red Hills of Dundee. Field preparation and transplanting began in 1966 when David, along with his new spouse, Diana, founded The Eyrie Vineyards. By their first vintage in 1970, the Letts had established 8 acres, approximately half of which were Pinot Noir clones UCD 1A (Wädenswil) and UCD 18 (“Trout droit”). Pommard 5 would be added a few years later. After establishing some of his cuttings in Lett’s nursery vineyard in Corvallis in the spring of 1965, Coury found a suitable location for his vineyard, winery and nursery in Forest Grove and bought the property in 1965. He moved into a farmhouse on the property once owned by noted vintner Frank Reuter and planted his first vineyard at Charles Coury Vineyards in 1966. There is no evidence to indicate that Coury planted his vines in Forest Grove before 1966. The obituary of Coury’s spouse, Shirley, confirms that Coury’s first plantings in Forest Grove date to 1966. The obituary reads, “With her husband, she established Charles Coury Vineyards in 1966 on David’s Hill in Forest Grove, where they were among the earliest participants in the fledgling Oregon wine industry.” (www.blues-star.com/news/obituaries/3638.html). Today, 3.9 acres of Pinot Noir survive among Lett’s initial Dundee Hills plantings of 16 acres, and, along with Coury’s approximately 6 acres of surviving Pinot Noir, are the oldest Pinot Noir plantings in the Willamette Valley. Lett, who passed away in October 2008 at the age of 69, developed a gray-white beard in his later years and was so revered by his peers, he was affectionately called “Papa Pinot.” He received considerably more recognition than Coury, and deservedly so, since his Eyrie Pinot Noirs set the mark and won international recognition for the fledgling Oregon wine industry. At a Gault-Millau-sponsored tasting held in Paris in 1979, “Olympics of Wines of the World,” a number of non- French wines placed near the top. The following year, Robert Drouhin gathered an international distinguished panel of judges who blind-tasted the wines against burgundies from the cellars of Domaine Drouhin in Beaune. A 1959 Domaine Drouhin Chambolle-Musigny came in first, but David Lett’s 1975 Eyrie Vineyards South Block Reserve Pinot Noir took second, ahead of Drouhin’s Chambertin. Bill Hatcher, formerly manager at Domaine Drouhin and now a partner in A to Z Wineworks in Oregon), called the 1975 Eyrie Pinot Noir, “The communion wine of the Oregon Wine Industry.” Lett followed the European model of winemaking, relying on low yields, small lot fermentations and French oak barrel-aging to produce exceptional wines. He remained faithful to a consistent theme of classically styled Pinot Noir that aged incredibly well. He was innovative (rather than iconoclastic as some proclaimed), practicing leaf pulling to limit yields and vertical trellising, viticulture techniques now widely used in cool climates. He was a firm believer in organic farming, said to be heavily influenced by Rachel Carson’s book, Silent Spring. Published in 1962, the book decried the use of pesticides. Until the 1980s, Lett performed all the important vineyard and cellar work himself. Rene Chazottes, a master sommelier who first drank wine with Lett at Nick’s Cafe in McMinnville over twenty-five years ago and came to know him well during several visits during the ensuing years, told me he was impressed by Lett’s ambition and focus. As Lett walked his vineyard, he could point out among the many vines which were the most productive and which gave birth to the top quality grapes. Lett continued to hone his craft through a career spanning almost 40 commercial vintages, holding the distinction at the time of his passing of producing a single vineyard Pinot Noir longer than any other winemaker in the United States. In addition, he had the honor of producing the first New World Pinot Gris in 1970, a variety that was to become Oregon’s signature white wine. David’s son, Jason, assumed the winemaking and vineyard management reins in 2005 and the winery has not missed a beat (father and son pictured below).

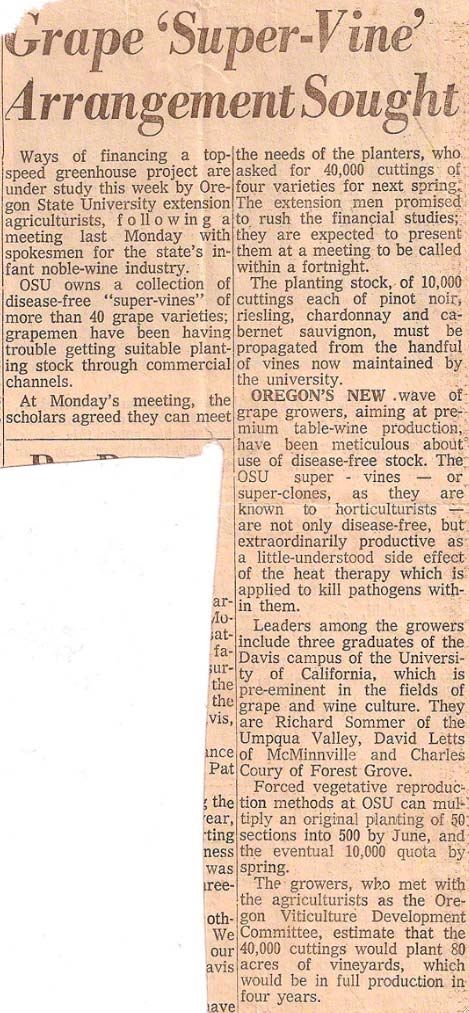

Coury, although extremely bright, never achieved the winemaking success of Lett. Dick Erath, when asked about Coury, is quoted in the Oregon Wine News interview (March 2011) as saying, “Unfortunately, he didn’t have the follow through...He just couldn’t get from A to Z.” Andrew Barr (Pinot Noir 1992) quotes Lett as saying, “Coury was a wonderful theoretician,” and therein may have been his downfall. Coury attempted to follow the California production model of the time, employing high yields and minimizing the importance of barrel aging. His wines, as a result, never achieved critical success and he was unable to develop a following. Coury finally left the Willamette Valley in 1978, ceding his winery to Dave Teppola who founded Laurel Ridge Winery on the site, later to become the David Hill Vineyard & Winery under the current proprietorship of Milan and Jean Stoyanov. After the sale of his winery, Coury became a pioneer in the microbrewing industry in Portland, but that venture was unsuccessful as well, and he returned to California where he passed away relatively anonymously in 2004 from lung cancer at the age of 73. Coury’s legacy will include working with other early vintners to establish a viticultural research center at Oregon State University, taking part in the formulation of ideas that led to Oregon’s labeling regulations and, along with Lett and Sommer, establishing quarantines on vine material (see Oregon newspaper article that references their work below). He also introduced the Pommard selection to Oregon in the early 1970s as part of a joint nursery venture with Dick Erath, as well as another Pinot Noir selection rumored to have come from Germany and which in Oregon is still known as the Coury clone.

In summary, the controversy of who planted Pinot Noir first in modern times in Oregon can be laid to rest. Richard Sommer, who put Pinot Noir into the ground in the Umpqua Valley in 1961, was the first. He was also the first vintner in the modern Oregon wine industry era to release a varietally labeled Oregon Pinot Noir (1967). David Lett holds the distinction of being the second to plant Pinot Noir in Oregon and the first to plant Pinot Noir in the Willamette Valley. He also was the first to plant Pinot Gris in the Willamette Valley. Charles Coury was the third vintner to cultivate Pinot Noir in Oregon and the second to plant Pinot Noir in the Willamette Valley. Lett and Coury established their first estate vineyards in 1966, Coury in Forest Grove and Lett in the Red Hills of Dundee. Forest Grove’s claim, “Where Oregon Pinot was born,” based on the evidence presented here, is unfounded, misleading, and should be retracted. Adam Campbell, who is the owner and winemaker of esteemed Elk Cove Vineyards in Gaston, near Forest Grove, said in the Forest Grove News Times (February 16, 2011), “Boasting about where Oregon Pinot Noir was born is really antithetical to the culture of how Oregon wineries sell our wine and educate people about the area. I think the slogan is divisive, probably not true and really not the most important thing about not only the city of Forest Grove but the winegrowing community that surrounds the city.” Jason Lett is in the process of creating an archival-rich website that will provide historians a valuable source of accurate information about David Lett and The Eyrie Vineyards. A sampling of releases from The Eyrie Vineyards, 2002 to 2009 vintages, follows.

A Tasting of The Eyrie VineyardsThe Eyrie Vineyards is named for the red-tailed hawks who nest (EYE-ree) in the fir trees at the top of the first vineyard plantings. The estate consists of four estate plantings in the Red Hills of Dundee. The 16-acre original planting at The Eyrie Vineyard is composed of 6.5 acres of Pinot Noir (Wädenswil UCD 1A and UCD 18) as well as Chardonnay, Pinot Gris, Pinot Meunier and Muscat Ottonel. This vineyard is the source of Estate Reserve Pinot Noir and special bottlings of South Block Reserve Pinot Noir ( a .9 acre portion, just 10 rows in the southern most corner of the Eyrie Vineyard planted to UCD 1A). The Daphne Vineyard (originally named Stonehedge), located above the original plantings about 400 feet higher in elevation, was planted in 1979 and 1980 and has 13 acres of Pinot Gris, Pinot Meunier and Pinot Noir (1.5 acres of Wädenswil UCD 1A/2A and Pommard 5). Rolling Green Farm, between Eyrie and Daphne, consists of 6 acres of Pinot Noir (4.9 acres of Wädenswil and Pommard 5) and Pinot Gris. Three Sisters Vineyard has 16 acres planted to the three Pinot sisters: Pinot Noir (4.2 acres of Wädenswil UCD 2A and Pommard 5), Pinot Gris and Pinot Blanc. Rolling Green Farm and Three Sisters vineyards were both planted in the late 1980s. Grapes from all four vineyards are blended to produce Eyrie’s Estate wines. Sustainable farming has always been the rule at The Eyrie Vineyards, and the own-rooted, non-irrigated vines have never been treated with insecticides, herbicides or systemic fungicides. David Lett’s wines were often light in color and body, less appealing in their youth, yet remarkably age-worthy. For Pinot Noir, he believed in picking early enough to retain what he considered the grape’s essential character. De-stemming and inoculating whole berry fermentation were common practices in the cellar, with occasional chaptalization in cooler years. Neutral oak was used almost entirely for aging that lasted 11 months for the Estate Pinot Noir and 18 to 24 months for the Estate Reserve wines. The Pinot Noirs were unfined and rarely filtered. The original Chardonnay planted at The Eyrie Vineyards came from a special selection of vines at the Draper Ranch in northern California. The Reserve Chardonnay is made from these original vines, and represents a vineyard and barrel selection that compared to the Estate Chardonnay, has richer and more complex flavors. It is aged on unstirred lees in a combination of neutral and new French and Oregon oak barrels for 9 to 11 months. Both the Estate and Reserve Chardonnay are gently filtered before bottling. The Eyrie Pinot Gris is a blend of grapes from all four vineyards. It is fermented in stainless steel tanks and gently filtered before bottling. First produced in 1970, Eyrie Pinot Gris has set the standard for this varietal in Oregon. Pinot Blanc is a limited bottling made from Alsatian clones planted at Three Sisters Vineyard. Lett never wavered from his vision of how wine should be fashioned, refusing to try to please everyone. He never gave in to the more modern styles of Oregon Pinot Noir with their luscious and decked-out fruit, a style that Lett saw garner high scores and develop a large consumer following. He was a firm advocate of preserving the delicacy and nuances of Pinot Noir. In 2007, Lett expressed his preferences, saying, “Pinot Noir should be a Princess, not a monster. Who would you rather have dinner with?” Ted Farthing, Oregon Wine Board Executive Director, said of Lett in 2009, “For those who prefer their opinions strong and their wines elegant, David was your man. What an inspiration.” Before David Lett passed away, he handed the vineyard management and winemaking reigns at The Eyrie Vineyards to his son, Jason, who took over beginning with the 2005 vintage. Jason did not start out to follow in his father’s footsteps. He worked for a time at age 17 at Maison Joseph Drouhin in Burgundy, but the French his age were more knowledgeable about winemaking and intimidated him, causing him initially to be disinterested in pursuing a winemaking career. He was to obtain a degree in plant ecology from the University of New Mexico and then became a research assistant at Oregon State University, studying the farming of berries in the Willamette Valley. An opportunity to make wine at Bernard Machado Wines led to his BlackCap label (black cap refers to the name of a bird, a mushroom and a berry that are all native to Oregon), and a renewed interest in winegrowing and winemaking. Jason is now committed to preserving the “Eyrie style” at The Eyrie Vineyards, while fashioning a more “New World” gutsy Pinot Noir and Chardonnay, the result of long fermentation times and higher percentage of new oak, under his own BlackCap label.. All wines at The Eyrie Vineyards are estate grown. The total annual production of about 10,000 cases consists of Pinot Noir, Pinot Meunier, Pinot Gris, Pinot Blanc, Chardonnay, and Muscat Ottonel. The winery and tasting room is located at 935 NE 10th Avenue in McMinnville, housed in a former poultry processing plant. Visit the website at www.eyrievineyards.com for more information and to plan a visit to this historic winery for tasting Wednesday through Sunday. The majority of the following wines were tasted with Master Sommelier Rene Chazottes at the Pacific Club in Newport Beach, California and the comments include some from Rene as well as myself. Rene pointed out that the wines have a consistent style, are balanced, and allow the terroir to show through, with the Pinot Noirs typically showing a pleasant spiciness with dried herbs on the finish. All the wines were obtained directly from the winery. Many wines were also tasted the next day from a previously opened and re-corked bottle and held up beautifully, a testament to their balance and age ability. The 2008 Estate Pinot Noir and 2008 Black Cap Pinot Noir are sold out.

2008 The Eyrie Vineyards Estate Pinot Gris 13.5% alc., $14.50. · Moderate straw color in the glass. Aromas of tropical fruits, wax and roasted nuts. Richly flavored notes of apricot, apple and citrus sustaining to the generous finish. Mildly viscous mouth feel with bright acidity. Well-made with admirable balance. The benchmark for Oregon Pinot Gris. Serve with a spinach souffle, salad with cheese, or mild fish.

2009 The Eyrie Vineyards Estate Pinot Blanc 13.5% alc., 504 cases, $16.75. · Aromas of peach skin, pear and dried nori. Pleasing lighter-weighted flavors of pears, baked peaches, fig and toast, smoothly textured and light on its feet, showing slight viscosity and finishing clean and dry. Good.

2009 The Eyrie Vineyards Estate “Original Vines” Reserve Chardonnay 13.5% alc., 196 cases, $47, released April 2011. A selection of 8 barrels. · Light straw yellow color in the glass. A restrained style with shy aroma of lemon curd. Crisp, clean and juicy with primarily delicate citrus flavor and undertones of apple and pear and oak. Noticeable minerality. Shy fruit on the bright finish. Serve with veal or white fish. Good (+).

2002 The Eyrie Vineyards Estate “Original Vines” Reserve Pinot Noir 13.0% alc.. · True to the Eyrie style with a very light reddish-purple color. Shy, but lovely aromas of red berries, baking spices and rose petals. Bright acidity lifts the flavors of cranberries, cherries and pomegranates with herbs dominating the delicate finish. Holding up nicely. Good.

2004 The Eyrie Vineyards Estate “Original Vines” Reserve Pinot Noir 13.0% alc.. David Lett’s last vintage. · Very light reddish-purple color in the glass. Moderately intense aromas of black cherries and spice with red and purple fruit flavors that show good density, length and persistence. A very subtle note of dried herbs and oak bring up the finish. A marvelous, beautifully balanced and elegant Pinot Noir. The star of this tasting.

2007 The Eyrie Vineyards Estate “Original Vines” Reserve Pinot Noir 13.5% alc., $60. · Very lightly colored in the glass. Oak dominates the gentle fruit aromas and moderately rich flavors with a noticeable scent of caramel and chocolate and oak-spiced red fruit on the mid palate. Soft and elegant. Some length on the slightly bitter finish which leaves an impression of dried herbs in its wake. May pick up interest and intensity with further age as many 2007 Oregon Pinot Noirs have been prone to do. Good.

2008 The Eyrie Vineyards Estate Pinot Noir 13.5% alc., $28.75. A blend of four Eyrie estate vineyards with an average vine age of 29 years. · Noticeable increase in reddish-purple color in the glass over the 2007 vintage. Very fruity, even sappy dark berry aromas with a hint of fresh herbs. Ripe, sweet and more masculine with a pleasing blend of spices and black fruits, restrained but firm tannins, and impressive aromatic length on the generous finish. Still fine the next day from a previously opened and re-corked bottle. Very good.

2009 The Eyrie Vineyards Estate Pinot Noir 13.5% alc., $33, released April 2011. · Moderately light reddish-purple color in the glass. Reserved, but attractive perfume of raspberries and black cherries. A well-crafted wine that is refined and supple in the mouth, offering a vivid explosion of raspberry fruit that lingers until the next sip. The fruit seems “alive.” Very good (+).

2009 The Eyrie Vineyards Estate “Original Vines” Reserve Pinot Noir 13.5% alc., $60. Released April 2011. · Moderately light reddish-purple hue in the glass. Enticing aromas of strawberries, raspberries and melon. Perfectly balanced with a charming array of Pinot fruits showing more restraint than the Estate bottling, but offering more long-term potential. The epitome of the Eyrie style with a sexy silkiness, elegance and a touch of terrior-driven dried herbs on the finish. Showing a little oak vanillin now due to its young age. The harmony and breeding predicts a long cellar life ahead.

13.5% alc., 72 cases, $60. · A modern style of Chardonnay with aromas of tropical fruits, banana, and oak. Moderately showy flavors of pear, lemon curd and baked apple. Lacks delicacy and refinement, but will please lovers of this fruit-forward style. Serve with shrimp, lobster, or sauced fish. Good.

13.5% alc., $45. Made from Eyrie’s younger Pinot Noir vines and fruit purchased from other mature and naturally managed Willamette Valley plantings. · Moderately deep reddish-purple color in the glass. Noticeably more extraction and oak treatment in this wine compared to the Eyrie bottlings. The nose is flush with a panoply of darker stone fruit and berry aromas. The core of fruit is wrapped in firm tannins and displays an underpinning of subtle oak-driven flavors. Not particularly refined but has the fruit to capture your attention. Very good.

NV NV La Luz Special Edition Oregon Pinot Noir 13.5% alc., 261 cases, $35. A one-time limited edition created by winemaker Jason Lett, from a blend of two own-rooted vineyards: 50% Eyrie Rolling Green Vineyard Pinot Noir grapes and 50% Bishop Creek Vineyards. A share of the profits from the sale of La Luz wines will help cover the uninsured medical costs for a kidney transplant for Lupe Hernandez, the mother of three girls and spouse of Eyrie’s cellarmaster, Julio Hernandez. · Moderate burnished red hue with a slight aged patina. Complex aromatics featuring a mix of berries and cherries, spices, new-sawn wood, bramble and bay leaf. Medium-weighted flavors of cherries and cranberries with dried herbs in the background. Bright acidity with subtle oak accents and a dry, slightly salty finish. Tastes like an aged wine. Good (+).

|