Umpqua Valley, Oregon

H. Bruce Smith, who writes the blog, Umpqua Valley AVA News (www.umpquavalley.blogspot.com) has offered

some information about Richard Sommer, which has also been widely reiterated in the wine press. Smith has

created the website, www.forestgroveoregonpinotenvy.com to refute Forest Grove’s claims. Although DeMara

and Gale offered me invaluable verification of Sommer’s achievements, it is important to first review what has

been written about Richard Sommer in the most plausible wine literature over the last twenty-five years.

Richard Sommer is widely considered the founder of Oregon’s modern wine industry. Growing up, he made

wine at home and attended University of California Davis, graduating with a degree in agronomy, and later

studying range management at University of California Berkeley. According to Paul Pintarich in The Boys Up

North (1997), Richard Sommer left California in the late 1950s to establish HillCrest Vineyard on the site of a

40-acre old egg farm in the Upper Valley of the Umpqua, northwest of Roseburg. Adolph Doerner, whose

family planted wine grapes in the Umpqua Valley in 1888, assisted Sommer with the first plantings. Sommer

was particularly interested in seeking out an appropriate climate for White Riesling and Pinot Noir. Before

settling at HillCrest, he had conducted detailed studies of the weather in areas of the Umpqua Valley where

table grapes were being grown successfully. Roseburg stood out because it had the requisite amount of sun to

ripen grapes, possessed enough coolness to prolong the growing season, presented minimal threat of frost,

and had well-drained soils.

Sommer first planted grape vines in the Umpqua Valley of Oregon at HillCrest (also appears as Hillcrest)

Vineyard in 1961, the first post-Prohibition Vitis vinifera planted in Oregon. The original HillCrest plantings

were put in the ground in 1961, 1962, 1963, 1964 and 1968, and included Pinot Noir among the reportedly 35

grape varieties planted there.

Sommer also acknowledged the potential for wine grape growing, and in particular Pinot Noir, in the Willamette

Valley to the north, and he referred to the wine pioneers who arrived in the late 1960s and early 1970s as “the

boys up north.” Dick Erath, who was a classmate of Sommer’s in a course at the University of California Davis

in 1967, credits Sommer for encouraging him to move to the Willamette Valley. It has been reported that David

Lett and Charles Coury visited Sommer at HillCrest Vineyard before establishing their vineyards in the

Willamette Valley, but according to Diana Lett (David Lett’s surviving spouse), neither Lett nor Coury knew

about Sommer before moving to the Willamette Valley.

Sommer has been portrayed in the literature as an iconoclast, described as brilliant by many, but decried as a

loner and eccentric by others. Some have called him “erratic, stubborn, quirky and a little weird.” More

favorable impressions have also been forthcoming, including “energetic, with a subtle wit, and a keen sense of

observation.” He loved nature and the outdoors and devoted himself so fully to that passion, he had no time

for marriage and children.

According to the book, Vineyard Memoirs (2004), written by Kerry McDaniel Boenisch, a Douglas County

Public Meeting was held in 1971 with the topic, “Prospects of a Grape and Wine Industry for Oregon.” Charles

Coury, David Lett, Dick Erath, Ray Doerner and Richard Sommer were in attendance. Sommer reportedly

said, “Here in Roseburg we have a perfect climate for growing certain types of wine grapes such as White

Riesling, Chardonnay, Cabernet Sauvignon and Pinot Noir. I moved to Roseburg in 1960 and in 1961 I planted

4 acres of eight varieties of wine grapes. I was in full production in 1966, making 6,000 gallons of wine. In

1961 I started with a mother block of eight varieties including Gewürztraminer, Chardonnay, Cabernet

Sauvignon, Sauvignon Blanc, White Riesling and Pinot Noir.”

Anthony Dias Blue (American Wine: A comprehensive guide, 1988), stated that Sommers planted initially in

1961, using cuttings from the Napa Valley he brought to Oregon from California, and “moved to a rustic beadand-

bat winery and expanded his vineyard to include Cabernet Sauvignon and Pinot Noir in 1963.” However,

one source, The Winemakers of the Pacific Northwest (1977), states, “Sommer planted Pinot Noir from the

beginning.”

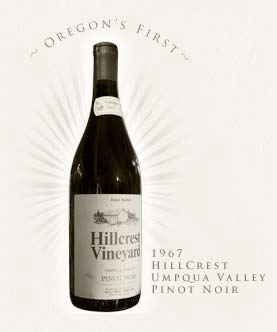

The HillCrest Vineyard winery was bonded in 1963 (Oregon Bonded Winery 44), the same year Sommer

released his first wine, a Riesling. We know he had commercially bottled a Pinot Noir-labeled varietal wine as

early as 1967. Dyson DeMara still has some bottles in his possession as shown in the photo below. This was

a first for Oregon, and preceded the first Pinot Noir released by David Lett in 1970 at The Eyrie Vineyard

(labeled “Spring Wine”) and the first Pinot Noir commercially produced by Charles Coury at Charles Coury

Vineyards (although the exact date is undetermined, it was certainly after 1967).

I asked noted Pinot Noir scholar, John Winthrop Haeger, who wrote both North American Pinot Noir (2004) and

Pacific Pinot Noir (2008), to weigh in on the birthplace of Pinot Noir in Oregon since his published writings have

focused on the Willamette Valley of Oregon and do not reference Richard Sommer. Here is his response. “I

think it is accepted fact that Sommer planted Oregon’s first Pinot Noir in modern times, at Hillcrest, in 1961.

We know for certain that his first vines went into the ground in 1961, and we ‘think’ Pinot Noir was among the

varieties he planted in the first go, but he was white variety-oriented, so I suppose it is possible that Pinot Noir

was not planted until a year or two later.”

Even Charles Coury, who was not known for his modesty, acknowledged that Sommer preceded him to

Oregon, and is quoted in Vineyard Memoirs by his sister-in-law, Betts Coury, as admitting, “He (Coury) was the

second person to make a decent wine in Oregon behind Richard Sommer.”

With that as background, the following historical information was relayed to me by Phil Gale, many details of

which were independently corroborating and embellished by Dyson DeMara. This proved to be invaluable

information, since little documented information about Richard Sommer appears in the wine literature.

Phil Gale grew up tending orchards in Southern California. This background served him well, although he had

no training in viticulture when Sommer hired him in 1975. Gale met Sommer in 1970 while he was working in a

local mill and journeyed to Sommer’s vineyard to buy wine. Sommer became his mentor, teaching him

vineyard management and winemaking, and Gale was to become a devoted friend who worked for Sommer for

thirteen years, eventually becoming the vineyard manager and assistant winemaker at HillCrest Vineyard.

Their relationship was not always sublime, and Gale, who admits to being bullheaded, regrets responsiblity for

being fired at least a dozen times. In every instance, however, Sommer would call him the following day

asking, “When are you coming back to work?” Gale grew to revere Sommer, and when we spoke, Gale

became quite emotional to the point of tears while reminiscing about Sommer and his many accomplishments.

Gale emphasized to me over and over, “Everyone absolutely loved the guy. I never heard anyone say anything

negative about him.” Gale described him as gentle, generous and extremely respected by the Douglas County

community in Umpqua Valley. Although admittedly eccentric (in a good way), and Bohemian, he was a

prominent, admired figure whom the locals counted on for wine at a time when there were precious few other

sources in that small southern Oregon locale. Neighbors would flock to HillCrest Vineyard at the end of the

growing season, reveling in the harvest and participating in the picking of the grapes. Many would make

regular visits throughout the year to buy wine as well.

Sommer was of German-Swiss heritage and his father was a scientist. His mother was from Ashland, Oregon,

located at the southern end of the Rogue Valley, and his grandfather had a vineyard there. His grandfather’s

success gave Sommer confidence that winegrowing could be successful in southern Oregon. Sommer

graduated from the University of California Davis in 1957 and upon arriving in Oregon, worked in the Douglas

County assessor’s office.

Sommer first established his vineyard in 1961 with cuttings obtained in 1959 from Louis Martini’s Stanly Ranch

Vineyard in Carneros, California. The only grape variety not obtained from Carneros was Zinfandel that had

proved itself in the local vineyards of Ray Doerner and was obtained from the Doerner property. The original

vines were rooted in 1960 in the Winston area of the Umpqua Valley and transplanted by Sommer to his

property in 1961, the same year he assumed title of the 40-acre ex-egg farm near Roseburg in Douglas

County. The property was owned by the Conns, former area land aristocrats of the 1800s who lived on the

site.

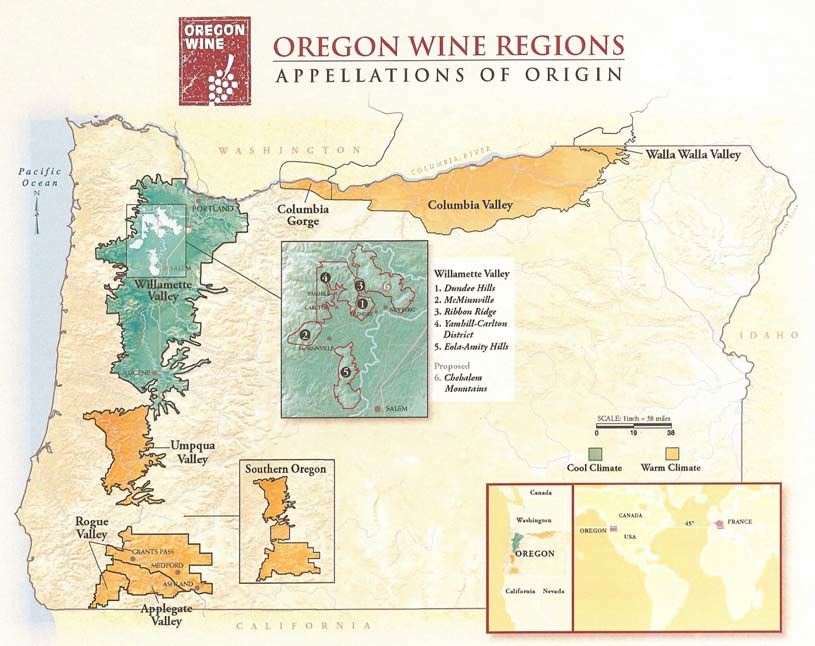

Because of the varied climates and complex mix of landscapes of the region, the Umpqua Valley (see map

below) proved to be suitable for growing both cool and warm climate grape varieties. When Sommer arrived,

there was no significant history of winegrowing to draw on, except the successful plantings of Ray Doerner

(whose family started Oregon Bonded Winery 7) and a few others nearby. As a result, Sommer planted

numerous varieties of Vitis vinifera as well as seeded and seedless table grapes, seeking to find grapes that

could thrive at his site. DeMara recalls that 35 varieties were planted at HillCrest Vineyard.

Gale emphasized, however, that Sommer was focused most specifically on Riesling and Pinot Noir, harboring a

special love for the latter. The marketplace demanded that he rely more on Riesling initially, because there

was little interest at the time in Pinot Noir as a distinct varietal.

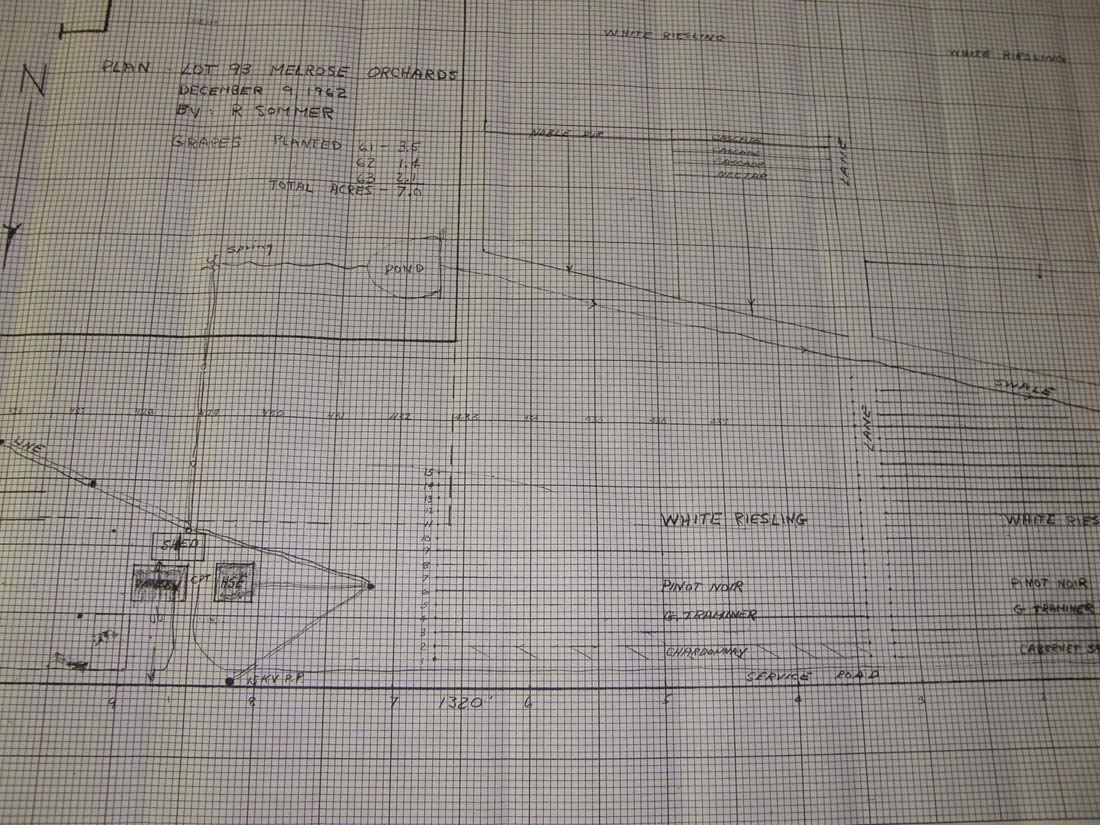

Sommer chose a plateau on his property at an elevation of 850 to 900 feet to plant his first vineyard. There

was a good layer of topsoil down 3 to 4 feet underlain with sandstone. Gale’s recollection and Sommer’s

master planting map from 1962 supplied to me by DeMara (see below) indicate that in 1961 Sommer planted a

total of 3.5 acres, consisting primarily of White Riesling, Chardonnay, Cabernet Sauvignon, Gewürztraminer,

and Pinot Noir (rows 5,6,7 and 8 in the vineyard). There were 50 vines in a half row, making the initial

plantings of Pinot Noir about 400 vines. All the Pinot Noir was Pommard clone. Trellising was Geneva Double

Curtain. Additional White Riesling was planted in 1962 (1.4 acres) and 1963 (2.1 acres), bringing the total

vineyard acreage to 7 acres by the end of 1963.

Further plantings of Pinot Noir and White Riesling and tiny amounts of other varieties (including Semillon,

Sylvaner, Sauvignon Blanc, Malbec and Gamay Noir) followed in 1964 and 1968, all in larger blocks than in the

first plantings. The 1964 plantings were established in an area north of the original vines in what had been

known as the Fraun Vineyards after the German who had previously owned that land. DeMara notes that the

1968 plantings of Pinot Noir vines which included UCD 18 selection, are the oldest remaining Pinot Noir vines

on the property, and included UCD 18 selection, some of which remain. Pinot Noir was also planted, managed

and sourced by Sommer on adjacent properties owned by others including Vern Anderson who bequeathed his

vineyard to Sommer upon his death in the late 1970s. Sommer eventually farmed a total of 50 acres of

vineyards at HillCrest Vineyard.

Sommer’s farming was organic minded, but fungicides were employed out of necessity when sulfur spraying

proved inadequate in some vintages. The vines were dry farmed, enabled by the adequate rainfall in the area

(Gale recalls as much as 35 inches a year). Rain was always a threat at the end of the growing season, but

Douglas County often benefited from a couple weeks of Indian summer that propelled the ripening process.

Although forty or so neighbors picked the grapes at harvest in the early years, Sommer eventually employed a

small well-trained crew of workers to perform the task.

Conifers were planted on the property on lower ground that rose up to the bench where the grapes were

established. For years, Sommer sold the conifers as “you cut” trees at Christmas to supplement his income.

One of the biggest challenges to farming grapes at HillCrest Vineyard was the ravenous birds who had a

special liking for Pinot Noir. A number of defenses were used including 12-gauge shotguns, propane cannons

and taste deterrents. In 1975, Sommer came up with the idea of using radio-controlled airplanes painted to

simulate hawks. This turned out to be a very effective deterrent. Netting was finally employed despite its

added cost to the the additional labor required and the expense of the nets. Gale cleverly devised a method of

fusing the individual rows of nets, creating a circus-style tent over multiple rows.

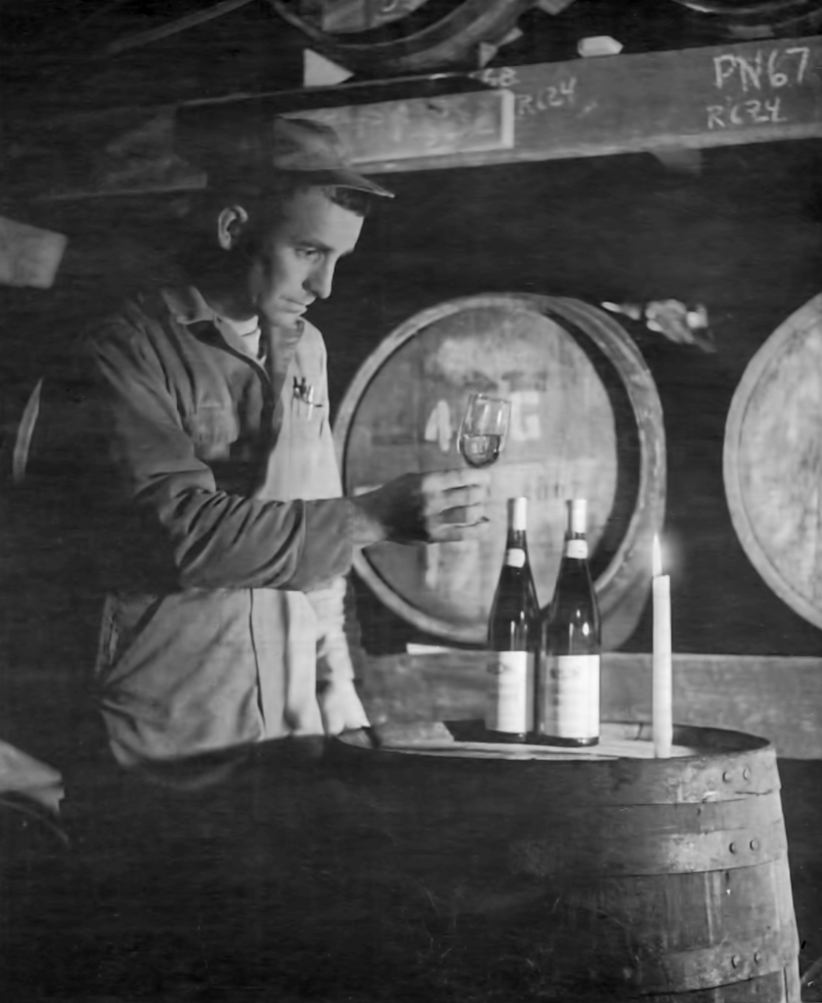

Sommer was a rather diminutive figure patrolling his vineyards, only 5’6” in height, and often wore a signature

beret and blue coveralls. Gale notes that Sommer had almost a “Buddhist reverence for nature.” He always

kept a notebook with him and chronicled his every vineyard activity in detail. He was an inveterate note-keeper

and his pockets were always filled with his writings. He was also obsessed with weather monitoring including

measuring the sun’s radiation, and his weather acumen bestowed on him a “sixth sense” of when to pick his

grapes. DeMara still has many boxes of climate records from Sommer’s past.

Sommer was also frugal. During one vintage, the crew was bottling splits and Sommer insisted on cutting the

corks in half, doubling their usefulness! He refused to buy any equipment to replace what he could repair

himself, not only to save money, but because he truly loved old equipment and enjoyed tinkering, repairing, and

jury-rigging it. For example, Gale recalls his fashioning a wooden worm gear for the bottling line.

The first commercial HillCrest wine, a Riesling, was released in 1963, and the first commercial Pinot Noir came

in 1967. DeMara reported that a visitor to Sommer’s house recalled seeing and being served bottled Pinot Noir

from as early as 1963, while Gale dates the first Pinot Noir to 1964. In the formative years, Pinot Noir was

blended with some Gamay. There was little market for Pinot Noir at the time and most of Sommer’s early

success was built on a blend of Riesling and Cabernet Sauvignon vinified with residual sugar and named

Mellow Red that was sold in gallon and half-gallon jugs. Other red blends, Umpqua Red and Dago Red, were

also produced for a short time. Early on, elderberry wine was also a component of Mellow Red, but this was

stopped after wine authorities discovered the practice. Mellow Red was still in production when DeMara

acquired the property in 2003.

Sommer’s HillCrest Vineyard Pinot Noirs were inconsistent, often a victim of the vintage climatic vagaries. The

1970, 1978 and 1979 wines benefited from warm weather and these Pinot Noirs were said to be “amazing” by

Gale. There was little recognition for the wines within Oregon, but the distributor for HillCrest wines raved about

them publicly. Gale was emphatic to me in his praise of Sommer’s Pinot Noirs, but admitted that the wines

were “spotty” in some vintages.

Sommer has been credited in the literature with being the first in Oregon to put the name of a grape variety on

the label of his wines, but this is inaccurate and there were others who preceded him. Botryitis was not unusual

in Sommer’s vineyards, and in 1978 he crafted Oregon’s first modern era ice wine. He also produced sparkling

wine at HillCrest Vineyard.

Interestingly, Sommer’s wines were fermented in a cement pit, bucketed into a press and raised in barrels. In

the case of Riesling, whiskey barrels were used, imparting an unusual flavor to the wines. The Riesling was

styled in a Moselle fashion with high acidity (0.9 g/100 ml) and some residual sugar (2.5 g/l). With Pinot Noir,

grapes were usually de-stemmed, but occasionally whole clusters were crushed or added back for added

astringency. Although punch downs were used, Sommer also employed a technique in which the cap was

allowed to drop on its own, up to three weeks after the initiation of fermentation. Called flavonoid reduction,

this extended maceration produced high tannins, but when the cap dropped, the tannins would soften

appreciably. The grapes were usually picked at 23º to 24º Brix. Typically, an alcohol level of 13% was

achieved, sometimes with the benefit of added sugar. Elevage of Pinot Noir took place primarily in French oak

barrels, with some Oregon oak barrels included.

Although initially Sommer worked with very rudimentary winemaking equipment, he had the resourcefulness to

repair it when it broke. Until 1965, his winery was housed in a former tiny egg storage room. In 1975, a 10,000

square-foot winery was built on the property, and the egg storage room became a wine library vault. Gale, who

helped built the winery, fondly recalls sitting in the rafters of the partially built winery at lunchtime with the

construction supervisor, Bud Anderson, and enjoying Sommer’s wines.

The Willamette Valley had a market for Sommer’s wines, but tiny Roseburg (about 11,000 people at the time)

could not support HillCrest as it expanded. Production in 1966 of 6,000 gallons had reached 30,000 gallons by

1987 with Riesling and Pinot Noir being the biggest sellers, and Sommer turned to a distributor to move the

wines into markets outside of the Umpqua Valley. Sommer had a business sense and originated the idea of

wineries offering barrel tasting tours to attract consumers.

Dyson DeMara took over HillCrest Vineyard in 2003. He had met Sommer in 1999 and spent time with him

both before and after assuming control of the winery. Regretfully, Sommer’s sister consigned many of

Sommer’s records to trash after the winery was sold. She has kept boxes of undeveloped photographic film

that Sommer, who was an avid photographer, had accumulated. Some records remain in DeMara’s

possession, but DeMara has not had the time to thoroughly research them.

When the winery was sold in 2003, much of the original plantings were dead, primarily from the fungus, Eutypa

lata (Eutypa dieback disease). DeMara pulled out most of the original 1961 plantings in 2004, including all the

Pinot Noir (he retained a few removed Pinot Noir plants for archival purposes), leaving some Chardonnay,

Riesling and Sylvaner. Of the original vines rooted in 1961, 1962, 1963, 1964 and 1968, 13 acres remain at

HillCrest Vineyard, primarily consisting of the 1964 plantings.

Sommer never sought out recognition for his remarkable career, leading several writers and friends to remark

over the years that he had not received the acknowledgement he deserved. He never exhibited any malice to

those who found him eccentric. Toward the end of his career, he was a bit remorseful, saying, “I regret that I

never tooted my own horn.” Sommer passed away July 28, 2009, at the age of 79. A memorial was held in his

honor on September 27, 2009. The Letts were unable to attend but Diana wrote DeMara and offered her

condolences, “My husband David always enjoyed his friendship with Richard, stretching over 40 years, and we

respected Richard’s position as the first person in Oregon to grow Pinot Noir. Although I visited with him only a

few times over all the years we shared as ‘Oregon Wine-Folks,’ I will remember Richard with affection and

respect.”

Largely due to the efforts of Dyson DeMara and others, Sommer has finally received the long-overdue

recognition he deserves. A House Resolution ordered on May 20, 2011, by the 76th Oregon Legislative

Assembly, commemorates both Oregon wine industry pioneer Richard Sommer and the 50th anniversary of the

planting of the first Pinot Noir vines in Oregon. A copy of the resolution follows.

Richard Sommer is held in high regard by the Umpqua River Valley community and has received a prominent

place in the Douglas County Museum of Natural & Cultural History in Roseburg. For those with curiosity, the

Museum is currently offering an exhibit titled “Wine: A 10,000 Year History,” which traces wine from its earliest

roots in the Middle East to the Umpqua River Valley, “America’s last great undiscovered wine region.”

Certainly, “undiscovered” is an apropos description of Richard Sommer’s contributions to Oregon’s rich wine

history.

Visitors are welcome at HillCrest Vineyard where one can view bottles of Oregon’s first Pinot Noir and see

Pinot Noir vines dating to 1968. Look in on the website at www.hillcrestvineyard.com. to see HillCrest’s current

wine offerings and to plan a visit.