The Demise in Popularity of Critical Wine Score Pronouncements

“Have you ever wondered what it might be like if wines scored humans….or decided to score wine

critics? Would wines be more sympathetic to us than we are to them?”

Ron Washam, HMW, HoseMaster of Wine™

The 100-point scoring system has been the standard way to rate wines used by nearly all wine

publications since its introduction by Robert Parker, Jr. in 1983. At the time Parker introduced his

scoring system, wine quality standards were nowhere near what they are today. As a result, it is rare

to find a wine today that deserves a score below 80, resulting in essentially a 20-point rating system

that has little range to differentiate wines because of compression of scores around 90 points.

The vast majority of domestic Pinot Noir wines over the past several vintages fall in the 87-93 point

range as judged by many wine publication reviewers. In essence, this range becomes the “average,”

with scores at or below 86 becoming below average and scores of 93 and above considered above

average, even outstanding or extraordinary.

In the October 15, 2018 issue of the Wine Spectator, 739 California Pinot Noirs, mostly from the 2015

vintage was rated for the report. The range of scores was 81-95. The average score for all rated

wines was 88.5.

The Wine Enthusiast website reports that 2,024 domestic Pinot Noirs were reviewed and scored

through October in 2018. The range of scores was 80-99. The number of scores in each numerical

range was as follows: 98+ 4, 94-97 223, 90-93 1,115, 87-89 535, 83-86 141, 80-82 6. 78% of the

wines fell into the approximate “average” range of 87-93.

The inflation of scoring over the past several years has been recognized by many. This trend has

diluted the value of a 90 point score which has, in essence, become “average.” When this score

inflation is combined with the compression of the scoring range, the result is that more wines are

pushed into the 92-96 point range, even though they might not be worthy of such praise judged by

past standards.

A review of all my wine scores for domestic Pinot Noir published in the PinotFile from 2013 to 2018

indicated a slight increase over this six-year interval. Here are the averages of all scores for each

year: 2013-89.6, 2014-90.4, 2015-90.2, 2016-90.7, 2017-91.0, and 2018-91.3. It should be noted that

the sample of domestic Pinot Noir wines I am offered for review is skewed and predominantly fall in

the premium or ultra-premium category. For example, in 2018, all Pinot Noir wines that scored 90 or

above in the PinotFile had an average price per bottle of $56.00.

Measurable differences between a rating of say 89 or 90 are vague, but the distinction between a

score of 89 and 90 holds considerable significance for both the wine’s producer and the consumer. 90

is the acknowledged threshold below which a wine is considered very good yet more challenging to

attract a market. A score of 90 indicates a significant step up in perceived quality and desirability and

can be more successfully promoted.

There are multiple drawbacks to the 100-point scoring system. Its interpretation is not consistent and

nearly every wine critic utilizes the 100-point rating system differently. The result is that the scores are

not strictly comparable from one wine critic to another.

A recent article in Food & Wine, www.foodandwine.com/wine/wine-critics, titled “In Their Own

Words, This Is How Seven Professional Wine Writers and Critics Go About Rating a Bottle,” confirmed

the highly variable approach wine reviewers use to arrive at a wine’s score.

Grading has become an estimation of a wine’s overall quality without specific points assigned to color,

aroma, flavor, texture and finish that was Parker’s original intent for the 100-point scoring system.

Scoring is highly subjective, often based on personal taste, pleasure and emotion with many wine

critics not giving credit to estimated age ability (although admittedly this is highly speculative in most

cases anyway).

David Morrison, who pens The Wine Gourd at www.winegourdblogspot.com, looked at the poor

mathematics of wine quality scores. He pointed out, “Most wine commentators’ wine-quality scores

are personal to themselves. That is, the best we can expect from each commentator is that their wine

scores can be compared among themselves so that we can work out which wines they liked and

which ones they didn’t. However, the scores cannot be compared between commentators at all. Wine

assessment is no better using numbers than words because the numbers violate many of the

mathematical requirements for a precise language.”

Tom Wark, an American wine blogger and respected wine commentator posting at

www.fermentationwineblog.com, similarly noted, “The thing is, I’m not aware of any wine reviewer

using ratings who claim that the number they attach to their written review is the result of a strict

equation or a form of mathematical logic. It is, rather, a way for them to express their appreciation of a

wine relative to other wines.”

Leading French wine critic Michael Bettane has recently weighed in on the subject of wine scoring. He

notes, “An absolute score serves only to flatter the self-esteem of wealthy buyers….while the rest of

us must surf the top-scoring options in search of wines within our price range.” He concludes, “A

whole bunch of arithmetic scores is not the way to educate consumers about wine. What we critics

have to do is teach people to compare their tasting sensibilities with our own….to discover what they

like or what they are seeking based on the reviews we provide.”

It is challenging for a consumer to align himself with the palate of a wine critic because everyone has

a different sense of smell and taste is primarily determined by smell. About 90% of taste comes from

odor receptors that are genetically determined. According to a study reported in Nature Genetics in

May 2003, no two individual genotypes for smell perception are the same. In this study, 189 people

were genotyped and none of them had the same odor-related genes and thus lacked the same set of

odor receptors.

The Wine Market Council reported a study in 2017 that found Millennials (anyone born from 1980 to

2000) drank 42% of all wine in the U.S. in 2015, more than any other age group. These wine

consumers and I have two sons in this age group, could care less about wine scores and only know

about wine criticism because that is what I do. One of my sons told me, “My generation doesn’t know the name of one wine critic. We know a few writers for magazines through Instagram and that is about

it. We rely on friends for wine recommendations, but we also drink a lot of beer and spirits. No one

has the attention span to care about wine journalism, much less wine scores.” A high percentage of

millennial wine consumers now use social media such as Instagram and wine apps to find wine

suggestions and to post their wine experiences.

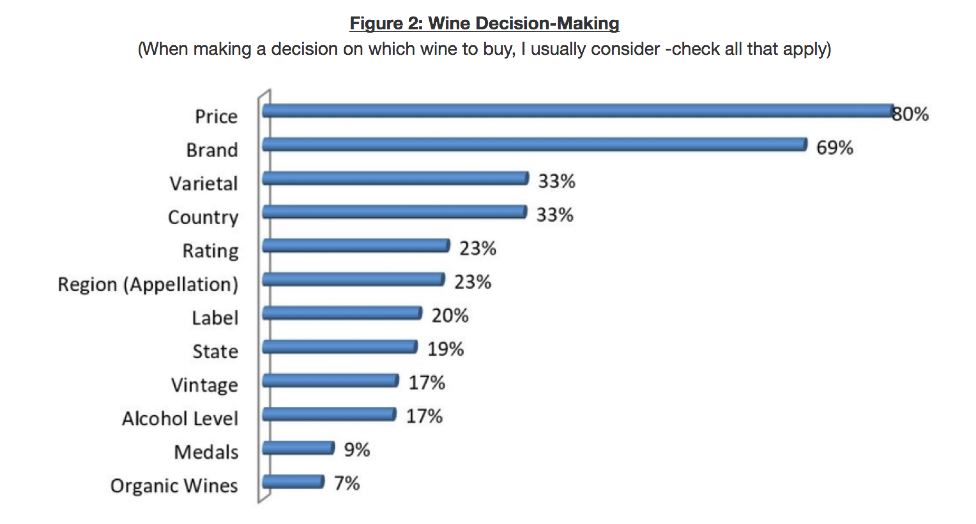

It is not just Millennials that are turning less often to ratings. A study by Sonoma State University in

2018 revealed the purchasing habits of the American wine consumer: www.winebusiness.com/

news/?go=getArticle&dataId=207060. 1,191 American wine consumers from 50 states were

surveyed. 2 percent were Generation Z (ages 21-23), 26 percent were Millennials (ages 24-38), 27

percent were Gen Xers (ages 39-53), 47 percent were Boomers (ages 54-74) and 7 percent were

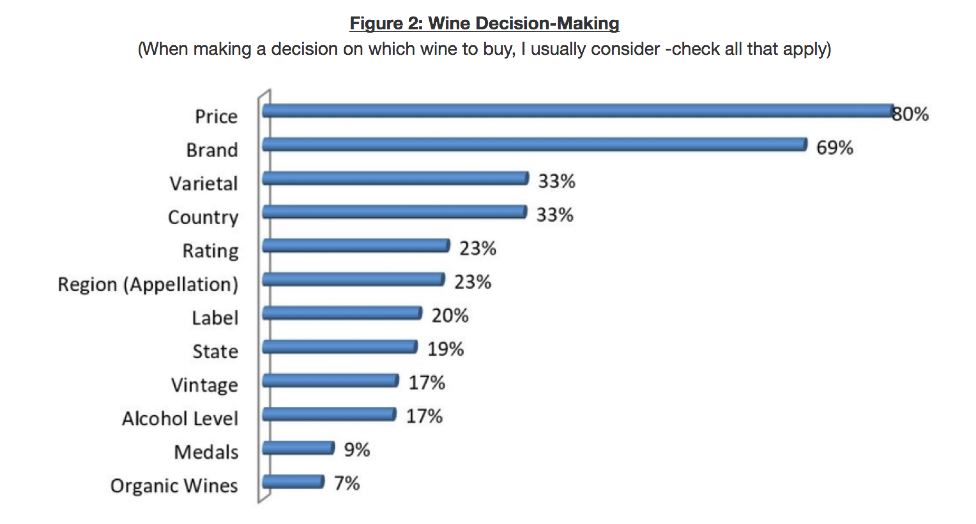

Greatest Generation (ages 75+). When asked about decision making when purchasing wine, price

(80 percent) and brand (69 percent) were most important, with ratings a distant fifth (23 percent).

Some astute wine consumers look closely at the descriptors in a wine review and find it of paramount

importance relative to the score. The description of the wine seems of greater usefulness especially if

the reader can see “between the lines,” and understands certain words or phrases that the writer uses

that are a tip-off indicating a special wine.

Wine descriptions would seem to be of most value to well-informed wine consumers, while others less

knowledgeable about wine look more to scores for guidance. As a writer and certified sommelier Katie

Finn noted, “Scores act like life vests to shoppers drowning in a sea of options. The idea is that

scores help people paralyzed with the fear of buying the ‘wrong’ wine.”

David Morrison pens The Wine Gourd at www.winegourd.blogspot.com and points out, “Word

descriptions of wine are frequently disparaged because it is often rather difficult to work out what all of

this flowery language is supposed to mean. This dissatisfaction is one reason why wine-quality scores

are popular because mathematics is supposed to make communication pedantically precise.”

Justin Howard-Sneyd, a Master of Wine has said, “Describing wine is not an exact science; wine and

taste are very personal and subjective. A wine that I think tastes of cherry, could taste totally different

to someone else, so it’s no wonder that there is such a vast variety of language when it comes to wine

descriptions.”

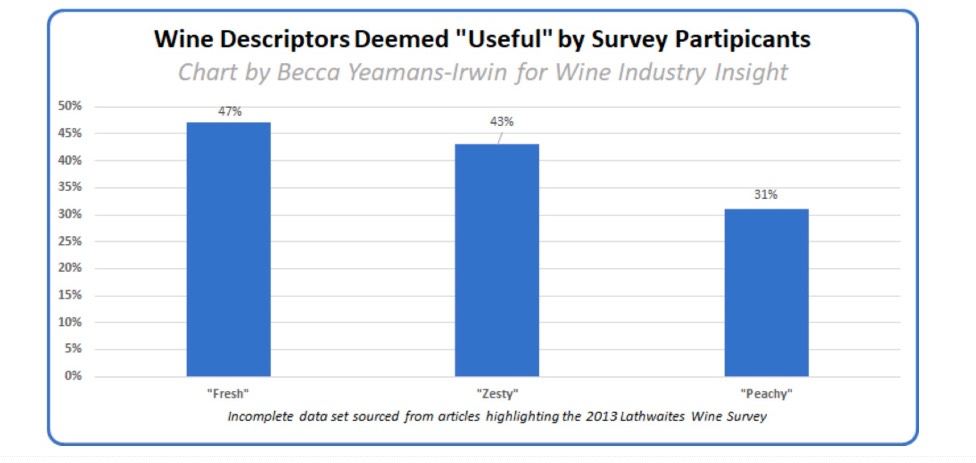

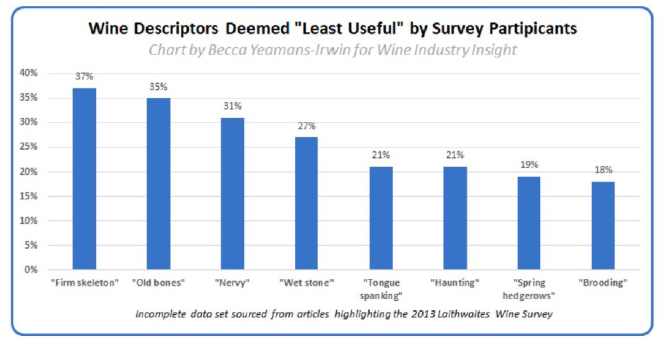

Some descriptors are simply more useful than others. The charts below are from the 2013 Lathwaites

Wine Survey in which those taking part said they were relatively well-informed on wine terminology.

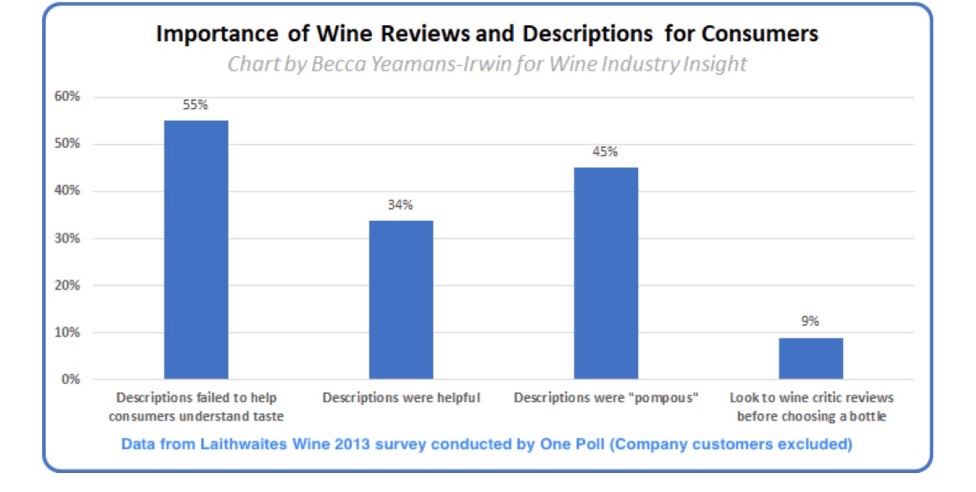

The first two charts show wine descriptors that are deemed “useful” and “least useful.” The third chart

reveals research that shows 55% of consumers found descriptions of no help in understanding taste

and 45% of the descriptions were considered “pompous.” Asked why the descriptions were not helpful,

responses included finding them meaningless, bearing no relationship to a wine’s taste, pretentious

and “a load of poppycock.”

The following charts were obtained from Daily News Fetch created by Wine Industry Insight, Lewis Perdue, Editor and Publisher, at www.industryinsight.com.

A common failing of wine scoring relates to wine reviews that don’t criticize wines or explain why they

give a wine a low score. Here is a recent wine review from Wine Spectator for a wine that received a

score of 87: “Wild sage, dark red cherry and turned earth show on the familiar nose of this bottling.

The palate is even-handed with red fruit and chaparral flavors.” If you only read the description of the

wine, what could you possibly discern about its quality or relate the description to the score?

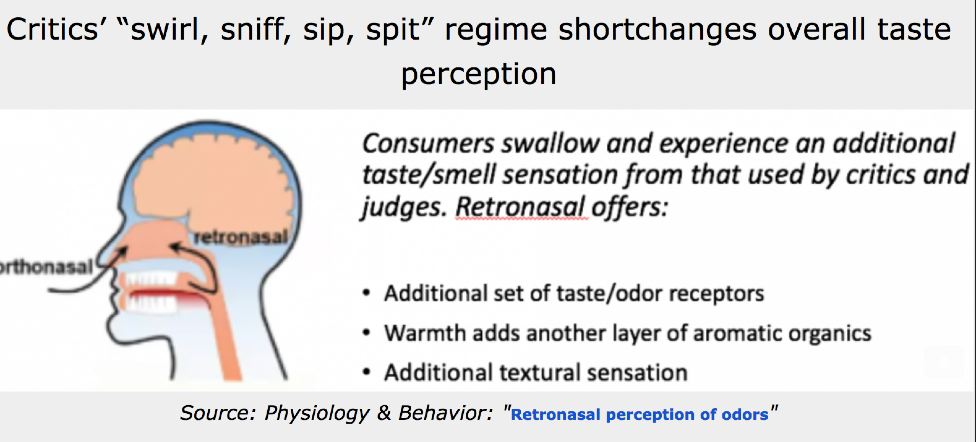

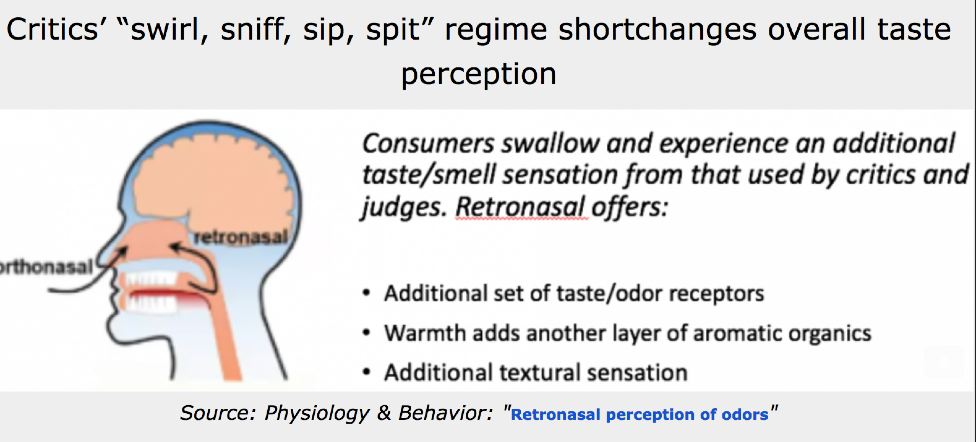

There is one drawback to professional wine reviews and not specifically to wine scoring that has to do

with orthonasal versus retronasal perception of odors. Wine critics use a regime of sniffing, sipping

and spitting but this orthonasal perception falls short of overall taste perception. Consumers swallow

and experience an additional taste/smell sensation known as retronasal perception of odors whereby

odors are perceived when they enter the nose through the pharynx in swallowing. A 2012 article in

Physiology & Behavior, www.ncbi.nim.nih.gov/pubmed/22425641, on the retronasal perception of

odors, pointed out that orthonasal and retronasal olfaction pathways convey two distinct sensory

signals. The full perception of wine is based on the interaction between orthonasal and retronasal

smell, taste and texture.

This is why I often taste wines in the morning with spitting and then re-taste some wines in the late

afternoon with a swallow. I believe this is rarely done by wine tasting professionals.

The 100-point scoring system clearly has many drawbacks but it has been and continues to be the

main driving force that sells wine. “Amazing Scores for Our 2016 Vintage Wines” reads the marketing

tagline for many wineries at this time of the year. The higher the score, the more retailers reference

them, the more wineries promote them, and the more influential the review becomes. Discrepancies

abound, however, with retailers known to quote scores for wines from a previous vintage or promote

lofty scores that lack attribution. Scores are hollow numbers if not used in conjunction with the score

assignor. Some sources quote scores from the Robert Parker Wine Advocate that the consumer may

still attribute to Robert Parker, Jr., yet he is only one of nine reviewers for the Robert Parker Wine

Advocate.

I have come to the realization that the current wine rating system may have outlived its usefulness. I

am not alone. Noted wine writer, Jamie Goode, said two years ago, “The 100-point scale is very

compressed at the top end….and this scale is becoming so bunched at the top end that it is nearing

the end of its useful life.”

Maybe we have reached the point that scores are no longer of any value to the current generation of

wine consumers in making purchasing decisions. Dwight Furrow, writing at www.3quarksdaily.com

on the purpose of wine criticism recently noted, “I almost never read wine reviews prior to purchasing.

I don’t need them for that purpose. I do read them after tasting the wine to learn more about what I’m

tasting. But also I like to check my impressions against others who have tasted the wine because it

teaches me something about my own palate and preferences.”

Recently, the Chinese have launched a wine rating system based on Chinese tastes that is aimed at

evaluating imported and domestically produced wines. As reported in November 2018 in The Drinks

Business, www.thedrinksbusiness.com/2018/11/china-launches-its-own-wine-rating-system/,

the Chinese wine rating system evaluates wines mainly based on color, aroma, palate and body using

a scoring scale of 10 points. The rating system is said to reflect China’s unique culinary traditions and

preferences. Apparently, a panel of judges consisting of members of the China Alcoholic Drinks

Association (CADA) and the China Wine & Viticulture Technology Association will do the ratings that

could lead to a national wine recommendation system. This critical wine reviewing system is not

revolutionary in that the 10-point rating system is simply another numerically-based scoring program.

George Vierra, who writes at www.georgevierrawinemaking.blogspot.com, described the Napa Valley College 25-Point Scorecard. This scoring system objectively analyzes wine's appearance, odor and taste for a total final score of a possible 25 points, and also includes a "Final Praises" section that includes further notes on wine style, ageing, food serving suggestions, price, value and where the wine can be purchased. My criticism of this scoring system is that it is but another variation of a mathematically-based scoring program and because it is based on 25 points, would only lead to challenges for the wine consumer to reconcile it with the 20-point and 100-point scoring systems.

So what to do with a wine rating system that may have outlived its usefulness and is of little interest to

the younger generation wine consumer?How can a new rating system be devised that won’t

invalidate the 35 years of published ratings based on the 100-point system? Can we create a wine

review with a noble calling, one that offers useful distinctions and criticism than one simply based on a

highly subjective and personal numerical award? Can we corral all the important professional wine

reviewers who are notoriously independent and have them use a standard review format that would

be truly comparable?