Winemaker Burt Williams: An Extraordinary Intuition for Crafting Pinot Noir (conclusion)

What was it that made Williams Selyem Pinot Noir so special? As a relative early mailing list member and

devotee I can tell you my impressions. The wines were simply magical and a 1992 Rochioli Vineyard Pinot

Noir made such a powerful impression on me that even today I can taste the wine, and clearly believe it was

the greatest California Pinot Noir I have ever had. Today, after ten years of writing only about Pinot Noir, I can

trace my long and winding Pinot trail back to that epiphanic bottle of Williams Selyem Rochioli Pinot Noir. The

Williams Selyem Pinot Noirs had a powerful charisma that turned on many devoted followers. Their reverence

was humorously depicted in a piece written by one of the winery’s devotees that was included in one of the

Williams Selyem newsletters. It read, “We are a little concerned about my brother-in-law, who had never tried

world class wine until we shared a bottle of your 1991 Olivet Lane Pinot Noir with him. Now he’s lost interest in

work and has moved the La-Z-Boy downstairs into the wine cellar. He claims he just wants to watch, but it’s

hard to say what needs matching down there. We’re hopeful that he is just displaying an initial zeal of a new

convert, and that he will return to a more normal life when he gets accustomed to venerating your wine.”

Another customer wrote the winery asking them to hurry with their next release because they had missed the

last one and their friends had stopped coming over.

Williams did not unnecessarily concern himself with the public’s attraction to his wines, and at least initially, was

surprised at their fame. When asked by wine writer, Donald Breed, in 1994, “Why is your wine so good,”

Williams answered, “You got me.” He was encouraged that consumers enjoyed his wines, but he was more

concerned with making wines that pleased himself.

The wines were usually moderately light in color, very fruity, charming and complex when young, with vibrant

aromatics that changed dramatically over time in the glass. Although delicious upon release, the wines would

age better than many California Pinot Noirs of the time. People were want to say, “These wines are so good

when young, they can’t possibly age.” Their age ability was in part due to their moderate alcohols and well-honed

acidity, as well as their impeccable balance. Balance was important to Williams as he has explained,

“Wine needs to be transparent and to be transparent, it must be balanced. Over ripe, over blown wines do not

reflect the site.” Williams also intended the wines to be food-friendly. He said, “I wanted the wines to be an

everyday beverage, not put on a pedestal.” A number of chefs were inspired by Williams and his wines. The

wines had perfectly ripe, sweet-like fruit flavors and supple textures, and the generous use of new oak

contributed a signature vanillin flavor. The terroir of the vineyards was apparent when tasting them next to each

other. The Williams Selyem wines peaked around 6 or 7 years after release, but well-cellared versions and

magnums lasted well beyond this. The quirky garagiste origins of the wines added to their mystique with their

scarcity contributing to the appeal, but the fact was, these were flat-out some of the greatest California Pinot

Noirs of their time.

The winemaking regimen would be considered routine today, but was innovative for California twenty-five years

ago. We might categorize it as natural winemaking. The Williams Selyem Pinot Noirs were largely made from

de-stemmed clusters. Only if the stems were ripe, and then only stems from chosen vintages would be

included in a modest percentage. Stems were not used in wines that tended to be tannic. Williams believed

that his customers did not relish tannic wines and so whole cluster inclusion was never allowed to impart

noticeable tannin to the wines. For example, the Mt Eden clones obtained from Hirsch Vineyard were very

tannic and the stems were never used. As to Rochioli Vineyard, up to 33%, and even 50% whole cluster were

included in the ferments.

Fermentations were always native, but changed dramatically in 1984. A government rebate was offered this

year on laboratory work to benefit the wine industry. Williams always wanted to isolate his own yeast that

would allow him to avoid filtration so he took advantage of this rebate. He developed a version of an

indigenous strain from Leno Martinelli’s Jackass Hill Vineyard, isolated by Vinquiry, a commercial laboratory in

Healdsburg. The old vineyard provided a perfect setting for wild yeast isolation. Pumice had been added back

to the vineyard yearly. The Saccharomyces yeast was strong, able to take grapes with high brix to dryness.

From 1984 forward, pre-fermentation maceration lasted 3 to 4 days, followed by inoculation with the Williams

Selyem proprietary yeast. Williams would remark, “The yeast always worked and there were no problems in

the bottle later on.” Today, the yeast is available to winemakers as the Williams Selyem strain.

Williams used his intuition to guide his fermentations which were dependent on the vineyard source and

vintage. If the fruit was pristine, he would do extended maceration. The first few days there was little juice, so

he would put waders on and tread on the grapes to get some juice freed up, then continue with punch downs

later on. There was no grape crushing per se. The best wines were produced with fermentations started cool

and slow, temperature rising in the middle and peaking at 88º to 90º at the end for 1 to 2 days. Temperatures

were checked frequently and good control was obtained with the cooling jackets of the milk tanks. The free-run

juice was siphoned to barrel by gravity while still warm and the remaining must and juice in the tanks was

removed with buckets for light pressing. Malolactic fermentation progressed in barrel after being induced,

finishing usually by the following January or February. The wines would be racked off their lees and different

blocks blended, with the wines barreled separately by gravity in March. The wines were usually unfined and

never filtered. They were hand bottled, labeled and foiled.

Williams chose his barrels after reading French texts. He discovered a 3-year study in Burgundy that

determined the best oak barrels for Pinot Noir were from Troncais oak from the Allier forest. He chose

Francois Frères as his preferred cooper, figuring, “If they were good enough for DRC, they were good enough

for Williams Selyem.” The amount of tight-grain French new oak used varied depending on the vineyard

source. He found, for example, the wines from Rochioli Vineyard were deemed too fruity initially and when he

increased the new oak to 100% beginning in 1985, the wine was more desirable. He remarked, “I didn’t want

fruit bombs. I was more concerned that the wines tasted like wine.” Elevage in oak varied from 11 months for

the Sonoma County Pinot Noir bottling to 17 months for the Rochioli Vineyard bottling. The barrels were never

used more than twice.

By 1997, Williams Selyem was producing more than 7,300 cases of wine annually. Williams was most

comfortable with about a 5,000 case production because this quantity allowed him to be in complete control

and fully hands on. Customers were clamoring for more wine and Williams Selyem had to often send back

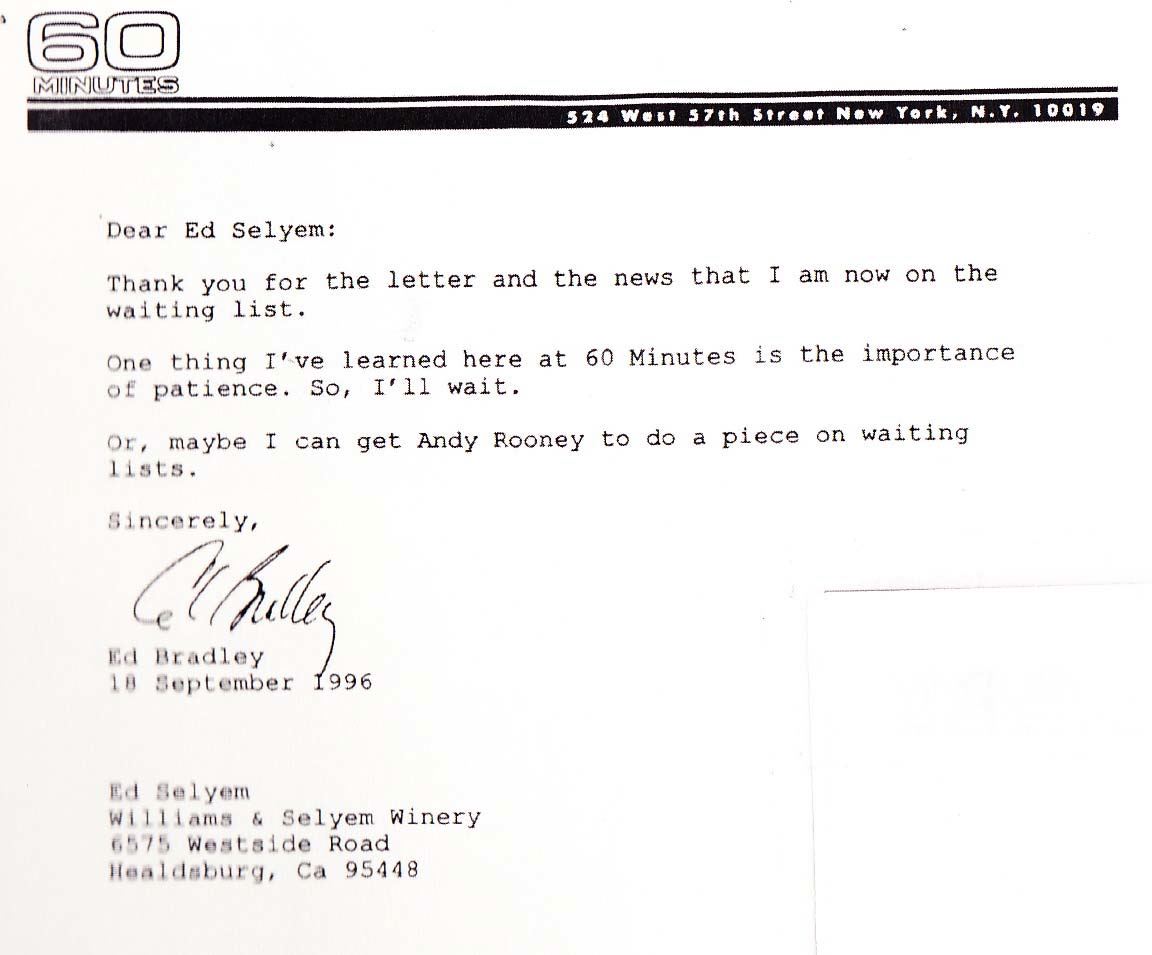

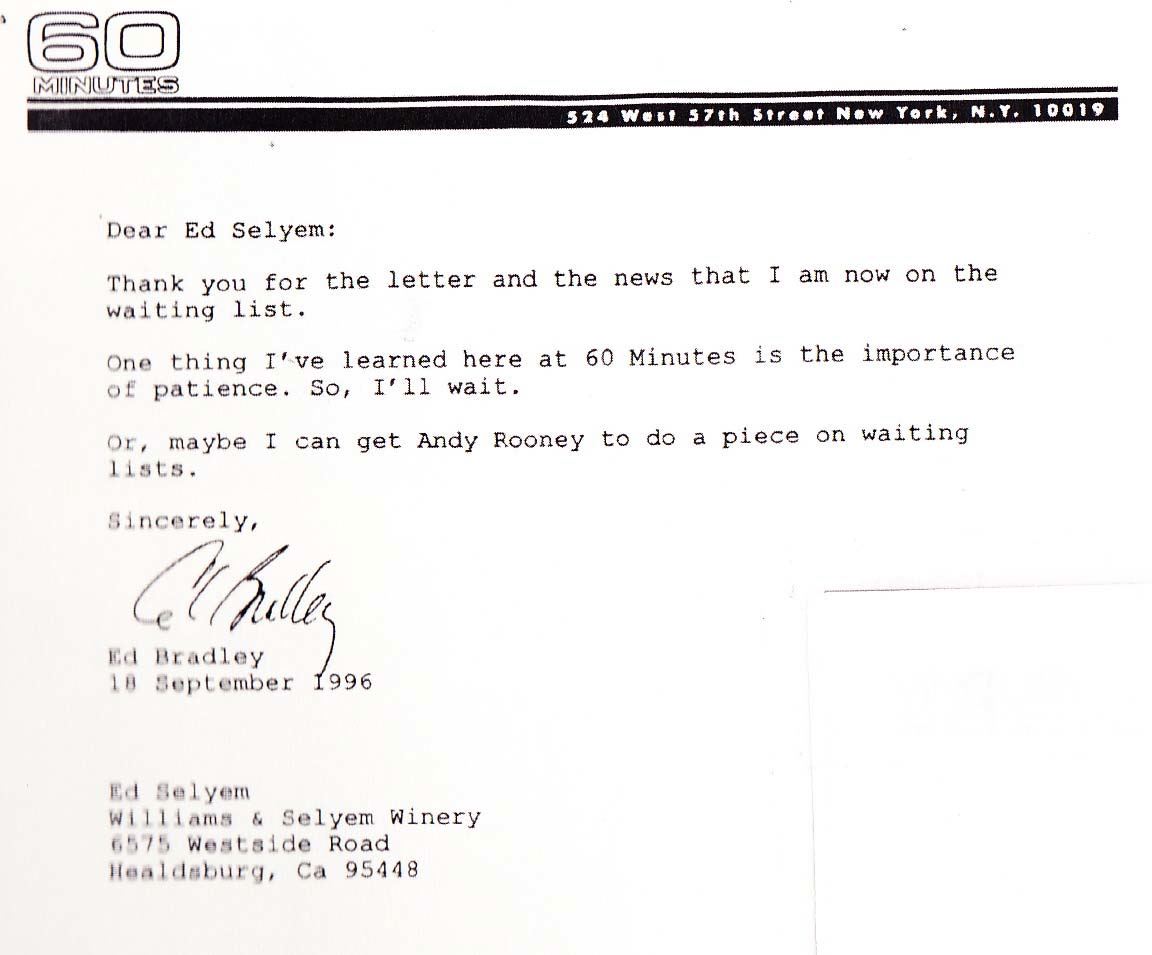

checks for as much as $50,000 in orders. Ed Bradley, a correspondent on CBS’s “60 Minutes,” was a wine

enthusiast who wanted to get on the mailing list in 1996. As you can see by the letter he wrote to Ed Selyem

below, he threatened to have Andy Rooney do a commentary on waiting lists if they didn’t add him to the

Williams Selyem mailing list. Williams said, “We couldn’t have that, so we added his name to the mailing list.”

Williams felt comfortable only delegating a few basic chores in the winery and he was working up to 16 hours a

day during and after harvest as a result. The winery, which began as a fun job, had escalated in complexity

and intensity. Writers and critics were constantly grading and judging the wines, creating more pressure and

causing the partners to drift away from their original intentions.

Ed Selyem’s back began to bother him, limiting his participation in some winemaking activities. He offered to

sell the winery to Burt, but Burt was unhappy working long hours and making more wine than he wanted. The

popularity of Williams Selyem wines had taken its toil over the years and the winery was finally put on the

market in 1997. After entertaining a number of suitors, including football player and wine aficionado Joe

Montana, Williams Selyem was sold March 1, 1998, to New York-based vintner John Dyson, a long time

member of the Williams Selyem mailing list, for a reported $9.5 million. Dyson essentially bought the name

and inventory of Williams Selyem, since Burt and Ed owned no vineyards or a physical winery. The last vintage

that Williams vinified at Williams Selyem was 1997. Williams was asked to consult at Williams Selyem for a

few years after the sale, but he could never put his heart in it, and after the 1998 vintage, left permanently. At

the time the winery was sold, there were 35,000 to 40,000 names on the mailing and waiting lists combined

according to winemaker Bob Cabral, who took over for Williams.

Williams kept meticulous technical notes regarding vineyard grape samples, weather, picking dates,

fermentation temperatures, vinification decisions, aging and so forth. Extensive tasting notes were also

preserved. These notes would prove invaluable to Bob Cabral when he took over the winemaking at Williams

Selyem in 1998, since initially he had no familiarity with the vineyard sources at Williams Selyem.

Williams had a number of favorite wines over the years including the 1983 Martinelli Zinfandel, the 1986 and

1995 Rochioli Vineyard Pinot Noirs, and the 1991 and 1995 Summa Vineyard Pinot Noirs. The 1991 Summa

Vineyard Pinot Noir was the first California Pinot Noir to sell for $100. The price reflected the tiny yields of .5

ton per acre of fruit which produced two new barrels of wine. A total of 1 ton of usable grapes was harvested

from 4 acres which worked out to a price of $5,000 per ton when you consider the farming costs for three

years, two of which - 1989 and 1990 - no usable grapes were obtained. Williams figured that if people wouldn’t

buy it, he and Ed would take it all home and drink it. As Williams said, “C-note or c-none.” The wine sold out in

three days.

The 1995 Summa Vineyard Pinot Noir sold for $125 and agin sold out right away. The 1995 Summa Vineyard

Pinot Noir was a prodigious wine. In the 1997 Fall Mailer from the winery, Ed Selyem’s tasting notes raved

about the wine. “Need a dictionary for adjectives. In the last four years, I’ve re-tasted practically all the best

producers’ grand cru red burgundies for vintages well over a decade including 85s and 90s. I’m sorry, without

prejudice, there has been nothing close to this wine.”

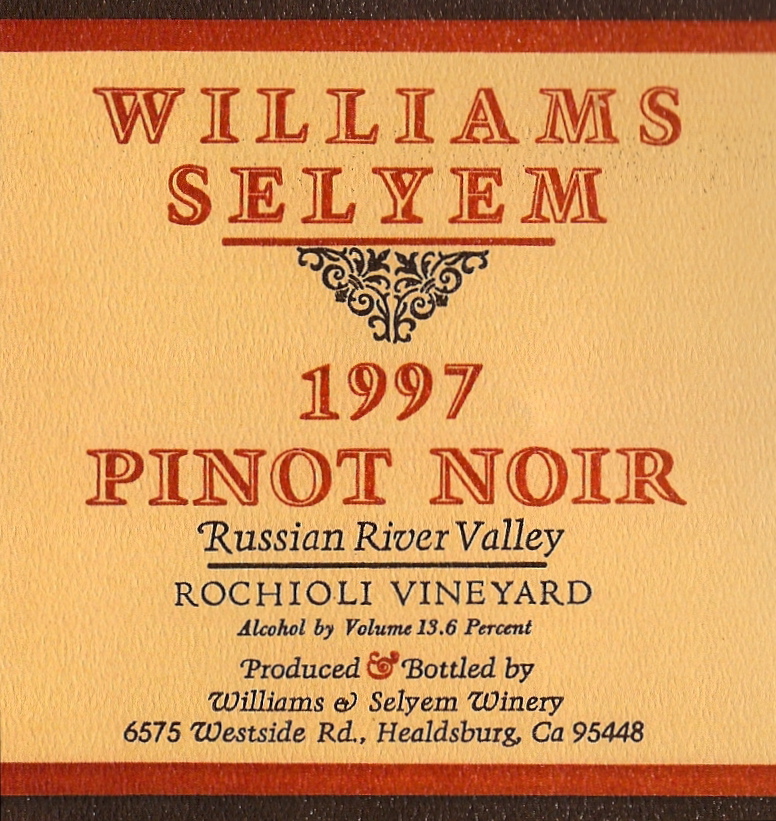

The last vintage of Williams Selyem Rochioli Vineyard Pinot Noir in 1997 also sold for $125 at Williams

request.

When asked to recall a few favorite story from his years at Williams Selyem, Williams offered the following. For

a number of years, Burt and Ed would meet annually with Jack Daniels and Win Wilson, importers of Domaine

de la Romanee-Conti, and sample each other’s wines over lunch. Williams recalls one bacchanal in 1992 or

1993 when the group, which included winemaker Chris Whitcraft, started and ended with Champagne and in

between, the small group drank 22 bottles of DRC and Williams Selyem, the “best Pinot Noirs in the world.”

Nothing sweeter than a Pinot Noir hangover!

In a 1987 newspaper article, Ed Selyem told the Press Democrat, “Our goal is to purchase some agriculturally

zoned land in the lower Russian River Valley so that we can continue to produce this quality of Sonoma County

wine on our own property.” This goal was never realized, and once the pair had a suitable production facility at

Allen Ranch, they were content. They soon had no desire to own an estate vineyard. At first they had their

other jobs and were too busy. After they quit their jobs and worked full-time at the winery, they had to

concentrate on making and selling wine and would have been spread too thin by also attempting to manage a

vineyard. Besides, they had talented growers they could rely on and mature vines to source from.

After the winery was sold, Williams bought a 40-acre property in 1998 in the Anderson Valley and planted 13

acres of Pinot Noir. Williams had looked at the Freestone area of the true Sonoma Coast and other cool

climate winegrowing regions as well, but settled on the Anderson Valley, in part because the land was more

affordable. Under the direction of vineyard manager Steve Williams (no relation), the land was cleared and

planted to cuttings from the Rochioli Vineyard, “DRC” suitcase selections from adjacent vineyards, clone 23

(Mariafeld - a clone Burt’s son favored), and Dijon clones 115, 777 and 828. The vineyard was named Morning

Dew Ranch. The soils are Franciscan type, clay underlain with sandstone. The vines were irrigated to

establish them initially, and some irrigation is required in certain vintages to ripen the fruit.

The fruit from Morning Dew Ranch has been released as a vineyard designated Pinot Noir by Brogan Cellars

(owned by Burt’s daughter, Margi Williams-Wierenga), Woodenhead, and Whitcraft. The agreements are, of

course, on a handshake basis. Williams crafted small amounts of Pinot Noir from his vineyard in 2008

and 2009, and with his ten year non compete clause reaching expiration in 2008, he released the two vintages commercially in 2010 and 2011 under the Morning Dew Ranch label. He has no plans to produce any wine after the 2009 vintage, choosing instead to enjoy his retirement.

Although the sale of Williams Selyem in 1998 cast a pall over many devoted customers, fortuitously a number

of aspiring vintners who spent time at the winery during the 17-year run of Williams Selyem have preserved the

Williams’ winemaking legacy in the many off shoots that now exist. The wineries include WesMar (Denise

Selyem and Kirk Hubbard), Davis Family Vineyards (Guy Davis), Papapietro Perry (Ben Papapietro),

Woodenhead Vintners (Nikolai Stez), Cobb Wines (Ross Cobb), and Mac McDonald (Vision Cellars). In

addition, Williams probably inspired more winemakers to make Pinot Noir than any other vintner in California.

The list of admirers includes a who’s who of New World Pinot Noir producers: Bob Cabral (current winemaker

at Williams Selyem), Michael Browne (Kosta Browne), Steve Doerner (Cristom), Ted Lemon (Littorai), George

Levkoff (george wines), Tim Olson (Olson Ogden), Manfred Krankl (Sine Qua Non), Jeff Fink (Tantara), Craig

Brewer (Brewer-Clifton), Tom Dehlinger (Dehlinger), Chris Whitcraft (Whitcraft), Tom Rochioli (J. Rochioli

Vineyards & Winery), Michael Sullivan (Benovia), and Thomas Rivers Brown (Rivers-Marie). There are still hundreds of other winemakers who revere him, although they may have never met him.

Williams also inspired his progeny to become winemakers. Daughter Margi, who was a teenager when her

father began making wine seriously in the 1970s at home, worked as a volunteer at her father’s winery in

Fulton before taking a paid position as an assistant to Burt and Ed in 1990 at the Allen Ranch facility. In 1998,

when Williams Selyem was sold, she decided to follow in her father’s footsteps and started her own bootstrap

winery, Brogan Cellars. In 2002, she won the Red Wine Sweepstakes Award at the Sonoma County Harvest

Fair. Burt and Margi are shown below at Burt’s Tribute Dinner.

Williams’ son, Fred B. Williams, Jr., also pursued winemaking and was the winemaker for Seven Lions Winery,

in Sebastopol in 1999, specializing in Pinot Noir, Zinfandel and Chardonnay. He tragically passed away at the

age of 38 from burns suffered in a truck explosion in 2003, but was memorialized with new wine labels, Fred’s

Hands and Seventh Domaine. The label was created by his former business partner, Charles A. Genuardi, and

Fred’s sister, Margi Williams-Wierenga. The wines were made from grapes crushed by Fred Williams in the

2002 and 2003 vintage before his accidental death.

Williams was such an iconic Pinot Noir winemaker, it would seem fitting to have a name for him. After all, Josh

Jensen of Calera Wine Company is “Mr. Pinot,” Merry Edwards of Merry Edwards Wines is the “Queen of

Pinot,” and Larry McKenna of Martinborough Vineyards and Escarpment in New Zealand is the “Prince of

Pinot.” For Williams, I thought of “Pontiff of Pinot,” but he is such a humble, regular guy, the nickname seems

like too much aggrandizement. I think just plain “Burt” is good enough, because when you mention Pinot Noir

and Burt in the same breath, everyone knows who you are talking about.

Burt Williams’ career will show that winemaking, like any craft, is a God-given talent, enhanced by education

and experience, but a craft for which some people are more blessed. The following are among the important

legacies of Burt Williams, his partner Ed Selyem, and Williams Selyem winery.

1. One of California’s ultimate cult wineries and the first for Pinot Noir.

2. California’s first $100 Pinot Noir.

3. First California Pinot Noir to be exported to Burgundy and offered on restaurant lists in Burgundy.

4. First winery to bring consumer’s attention to a sense of place reflected by specific vineyards such as

Rochioli, Allen, Olivet Lane, and Summa.

5. First vineyard designates from Allen Vineyard, Summa Vineyard, Precious Mountain Vineyard, Cohn

Vineyard and Olivet Lane Vineyard.

6. Emphasized that vineyard designated Pinot Noir should only be offered when the vineyard warrants it.

7. Turned the consumer’s attention to growers and their vital importance in fine wine production. Also set the

stage for vintners and growers to work together.

8. Fostered the winemaking approach now widely followed by Pinot Noir producers including hand sorting of

grapes, punch downs, and no pumping in the winery.

9. Brought to consumer’s attention the importance of choosing carefully the type of French oak used for aging

Pinot Noir

10. Developed a proprietary yeast that is now in wide use in Pinot Noir winemaking.

11. Brought worldwide recognition to the Russian River Valley and its wines, particularly Pinot Noir.

12. Originated the mailing list (and waiting list) model for selling wine directly to consumers.

13. Among the first California Pinot Noir producers to offer wines in magnum format for most bottlings.

14. Demonstrated that intuition through experience is invaluable in crafting Pinot Noir.

15. Most importantly, Williams Selyem showed that great wine, and in particular Pinot Noir, can be produced

without artifice. Technological methods such as saignée, alcohol adjustment, addition of Rubired extract, or

other products to change color, flavor, acid, tannin and mouth feel, are simply not required nor desired.

Technology and expensive equipment can be useful winemaking adjuncts but are not requirements for fine

wine production.