Pinot Noir Suitcase Clone “828”: An Intriguing Story Revealed

“It’s like a black dog. It (upright "828") doesn’t have the papers - the pedigree of a

black Labrador retriever - but it’s a good hunter (producer).”

Joel Myers, Vinetenders and Siltstone Wines, Oregon

Acknowledgements

The following people offered invaluable information for this article based on their experience with suitcase clone "828," and in some

cases, their personal association with Gary Andrus.

Adam Lee (Siduri), Anna Metzinger (Archery Summit Estate), Chad Melville (Melville Vineyards & Winery), Dick Erath (formerly Erath

Winery), John Haeger (North American Pinot Noir and Pacific Pinot Noir), Eric Hickey (Laetitia Winery & Vineyards), Jason Drew (Drew

Family Cellars), Jean Yates (retailer, Avalon Wine, Corvallis, Oregon), Joel Myers (Vinetenders & Siltstone Wines), Kathleen Inman (Inman Family Wines), Laurent Audeguin (French Wine &

Vine Institute), Laurent Montalieu (Hyland Estates, Soléna), Leigh Bartholomew (Archery Summit Estate), Michael Sullivan (Benovia),

Paul Lato (Paul Lato Wines), Peter Cargasacchi (Cargasacchi Wines), Sam Tannahill (A to Z Winery, Rex Hill Winery), Stewart Johnson

(Kendric Vineyards), and Ted Lemon (Littorai). Special thanks to David Adelsheim (Adelsheim Vineyard), who was the inspiration for

this article, and whose encyclopedic and intimate knowledge of Oregon’s wine industry history provided invaluable information and

critical editorial contributions.

Preface

An understanding of clones and related terminology is central to this article. For those who need a concise refresher before reading this

story, refer to the appendix at the end.

Some Pinot Noir Arrives By Suitcase

All Pinot Noir cultivars existing in the United States originally came from France, but many of these imports that

arrived in the 1930s and 1940s were infected with viruses. To control this problem, the Foreign Quarantine

Notices of 1948 (Part 319.27 of the USDA Plant Quarantine regulations) “ended uncontrolled importation of

clonal plant materials” and prohibited “importation or entry into the United States of any Vitis vinifera, except

with a permit.” The Quarantine Notice also required a post-entry quarantine period for grapevines, conducted

by a permit-holding plant pathologist. These regulations allowed grapes to enter the United States for

experimental or scientific purpose, but they could not be released until they were tested for viruses. Because

of inadequate funding and staffing at the USDA facility, there was virtually an embargo on the introduction of

new grape selections by the government for several years.

In 1952, Dr. Harold Olmo, a UC Davis faculty member in the Viticulture and Enology Department, formed the

California Grape Certification Association to find, maintain and distribute correctly labeled grape stock that had

been thoroughly virus-tested and chosen for vigor and fruitfulness. By 1958, the program was combined with

the UC Davis disease-tested fruit and nut program to become the Foundation Plant Materials Service (FPMS).

In 2003, “Materials” was dropped and the name shortened to Foundation Plant Service (FPS). This was the

first source of virus tested, certified stock available to winegrowers in the United States.

From the early 1950s until 1988, most of the grapes imported into the United States were controlled by UC

Davis. The FPMS program at UC Davis was in hiatus from 1989 until 1993 when the National Grapevine

Importation and Clean Stock Facility was opened at FPMS and imports into UC Davis were resumed. Several

selections of Pinot Noir were imported from France and Switzerland, including Pommard (UCD 5) and

Wädenswil (UCD 1A). These became the workhorse clones in Oregon vineyards during the 1970s and 1980s.

During the 1970s, there was widespread interest in clonal diversity, and John Haeger (North American Pinot

Noir, 2004) notes, “A wave of interest in clonal selection swept through the pinot-oriented winemaking

communities in both states” (California and Oregon). While the FPMS was concerning itself primarily with

screening, testing and certifying grape stock, winegrowers were interested in the diversity of clonal material

being investigated and available in France. Charles Coury was one of the first Oregonians to recognize the

French work with clones, having worked as an intern at the National Institute for Agronomy Research in

Colmar, Alsace, France, years before in 1964. In 1974, David Adelsheim, founder of Adelsheim Vineyard,

spent time at the Lycée Agricole in Beaune, which had the responsibility for testing the Chardonnay clones

selected by Dr. Raymond Bernard, a University of Dijon viticultural researcher. Bernard worked under several

agencies with the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries in Dijon and was also leading a much bigger program

selecting several hundred Pinot Noir clones. Many California winegrowers and winemakers also made

pilgrimages to France to discover the diversity of clones available.

Oregon State University obtained its own permit to import clonal material from European selection programs in

1975 thanks to a push from David Adelsheim and others. Adelsheim arranged the earlier shipments of clones

from Colmar (1975), Espiguette (1976) and Geisenheim (1978). In 1984, Dr. David Heatherbell, Professor of

Enology at Oregon State University persuaded Dr. Bernard at the Office National Interprofessional des Vins

(ONIVINS) to share some of his Pinot Noir and Chardonnay clones with Oregon. The first Dijon clones of Pinot

Noir (113, 114, 115) were brought legally into Oregon in 1984. The second set of shipments of Pinot Noir

clones (667, 777), were sent in 1988 as a result of a subsequent trip by Adelsheim. Chardonnay clones 76, 95

and 96 were also part of these first shipments of clones. The French Dijon clones were first shared with FPMS

in California in 1988-89. This program at Oregon State University was eventually discontinued upon the

retirement of the permit holder less than ten years later.

The laboratory technicians at Oregon State University had nicknamed the imported cuttings, “Dijon clones,”

after the return address on a shipping container of clones from Dijon, France. The name quickly became part

of viticulture lexicon. Dijon clones imported into the United States are designated by numbers assigned by the

French Ministry of Agriculture known as the Comité technique permanent de la sélection (Committee of

Selection of Cultivated Plants or CTPS) and include the most widely planted CTPS clones 113, 114, 115, 667,

and 777 (and more recently 459 and 943). FPMS assigned the same 3-digit numbers to the Dijon clones.

Charles Coury was presumably the first to smuggle cuttings into Oregon after working at INRA, Colmar, Alsace,

France, in 1964. A number of winegrowers and winemakers, primarily in California, and to a much lesser

extent in Oregon, did the same. Since the cuttings were often wrapped in wet newspaper and put inside a

suitcase, they became known as “suitcase” or “Samsonite” clones. Trench coats were also reputedly a favorite

accessory useful for smuggling cuttings into the United States. Haeger noted, “During the 1980s and 1990s,

illicit imports of grapevine budwood thrived.” These cuttings were field selections and not clones per se. Many

of the smuggled selections became the source of the so-called “suitcase” clones which formed the basis of the

heritage clones of Pinot Noir (Mount Eden, Swan, Chalone, Calera, Hanzell, etc.) now widely planted in

California.

It is nearly impossible to verify the lineage of suitcase clones since the original smugglers have been

understandably reluctant to admit to their transgression for legal and professional reasons. The French are

highly protective of their vineyard names and by the mid 1990s, they threatened legal action against any

Americans who were found to be using grapevine cuttings from their famous vineyards, especially if they were

vocal about it. Many rumors arose of suitcase material from such famous vineyards as La Tâche and

Romanée-Conti (so-called DRC clones) planted in California vineyards, but no one admitted to such a source

for fear of violating French intellectual property law, not to mention United States importation laws. The

plantings are simply referred to as suitcase or heritage clones in the viticulture trade and wine publications

today.

There is one suitcase clone, “828,” that is of great interest to Oregonians, and whose origin can be traced to a

single individual and winery, Gary Andrus and Archery Summit Estate. The complete and intriguing story of

“828” has never been revealed. I decided to research the pedigree of the “828” suitcase clone, but found that

some historic details could not be obtained because the central figure in this story, Gary Andrus, had passed

away, and those who knew him well and had first hand relevant information, could not reveal or confirm it

because of concerns over violating French intellectual property law and United States importation law. The

names of some of those who were intimately involved with the story as well as some particulars shall forever

remain off the record. In spite of these limitations, I offer a nearly full account of the lineage of suitcase clone

“828.”

The Real Dijon 828 First Appears and Eventually Emerges From Quarantine

The vineyards in the Côte d’Or in the late 1950s were performing poorly due to viral infestation, late harvests,

and archaic viticultural practices. The French had practiced selection massale in establishing and maintaining

their vineyards. The vignerons in Burgundy were generally dissatisfied with the quality of their wines and in

need of urgent assistance.

Dr. Raymond Bernard and other researchers of the late 1950s, conceived the idea of “clonal selection,” that is,

taking cuttings from vines showing no evidence of viral disease, yet possessing desirable characteristics to

create “mother” vines. These mother vines would then be used to establish new healthy vineyards and thereby

improve the quality of Pinot Noir and Chardonnay wines in Burgundy. Initially, Bernard’s ideas were scorned by

many vignerons in Burgundy and he was forced to use his own money and resources to conduct experimental

research in a vineyard in the Hautes Côtes. One vigneron who did support Bernard was Jean-Marie Ponsot,

who offered budwood from his vines in Morey-St.-Denis from his Clos-de-la-Roche vineyard as a source of

material for Bernard’s early Pinot Noir clonal trials. These cuttings were planted in an experimental vineyard at

Mont-Battois and from this stock came Dijon clones 113, 114 and 115 (certified in 1971), 667 (1980), 777

(1981), and others. The clones were descended from individual plants that were the most rewarding clones

showing disease resistance, good flavors, reasonable yields and proper ripening in Burgundy’s cool climate.

Over time, Bernard expanded his research, obtained cuttings from many vineyards in the Côte d’Or and

beyond, and not only planted vines in his experimental vineyard, but also in the vineyards of the Lycée Viticole

de Beaune (the seat of learning for viticulture and vinification for Burgundy’s wine industry). Bernard eventually

received the support of the French Ministry of Agriculture and other professional societies in France, leading to

increased funding of his research. He became the regional director of the Office National Interprofessional des

Vins (ONIVINS), the French National Wine Office. Bernard is considered the father of Dijon clones of

Pinot Noir and Chardonnay.

Clone 828 is one of 43 currently certified Dijon clones of Pinot Noir in the Catalogue of Grapevine Varieties and

Clones published by ENTAV-INRA® (L’Establissement National Technique pour l’Ameléioration de la

Viticulture/Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique, France). The ENTAV-INRA® trademarked clones

are registered and assigned a unique certification number by ONIVINS after approval by CTPS. The clonal

numbers are not of any special significance other than an accession number as each new selection has been

added to the CTPS system. All plants with a unique certification number were propagated from the same

parent mother vine, underwent ten years on average of rigorous testing and research before becoming

certified. The origin and authenticity of the clones is guaranteed.

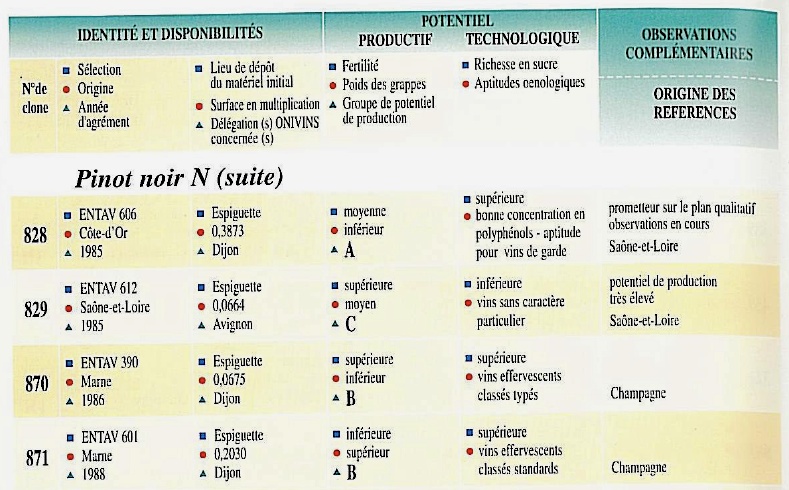

The pages of the 1995 edition of the Catalogue des Variétés et Clones de Vigne Cultivés en France list clone

828 as originating in Saône-et-Loire, a large department of France in the Côte d’Or and dating its registration to

1985 (refer to copy of entry below). Clone 828 has a recumbent or prostrate growth habit and is part of the

family of Pinot fin clones (sometimes referred to as Pinot tordu clones) that include Dijon 113, 114, 667, 777, etc, to

distinguish them from Pinot droît clones of Pinot Noir such as 374 and 583 which display an upward growth

pattern from the vine trunk. In an unhedged vineyard, Pinot droît clones are easily distinguishable from Pinot fin

clones which fall over. This distinction is central to the story of suitcase clone “828” because it is an upright

Pinot droît selection (more on this to follow).

Dijon clone 828 was never legally released in the United States. Rather it was kept in quarantine because it

was found to be infected with GLRaV-2RG, a grapevine red globe virus variant (often referred to as LR2RG,

GRGV or in common parlance, Red Globe, which is used in this article). Red Globe is one of several virus

strains belonging to the family Closteroviridae mainly associated with the grapevine leafroll disease complex.

This virus influences graft incompatibilities, bunch structure and fruit set. Haeger told me that once Red Globe

was discovered at UC Davis, ENTAV retested their mother vines and found they also tested positive for Red

Globe so they stopped distribution in France and everywhere else. Before that, 828 had been popular in

southern Burgundy in the Maconnais, although it was originally selected for northern Burgundy according to

Laurent Audeguin of the French Institute of Vine and Wine.

Heager has never found a credible report of real Dijon 828 having been suitcased to North America. “For my

money, there is no real 828 in North America until someone can point to vines with a recumbent growth habit

that test positive for Red Globe.” Adam Lee, proprietor and winemaker at Siduri Wines in Santa Rosa,

California, believes there is something out there in California being touted as true 828, but is unaware of any vines that have been verified as true 828.

True 828 has been brought into Canada through a Canadian nursery from France by Grant Stanley, the

winemaker at Quail’s Gate Winery in British Columbia. Adelsheim contacted him for confirmation and Stanley

told him that it was a recumbent clone and has low levels of Red Globe. The Dijon 828 clone is blended with

other Pinot Noir clones in Quail’s Gate Family Reserve Pinot Noir.

New Zealand has had experience with true clone 828. Several in New Zealand acquired true clone 828

fraudulently and have made single clone wines that reportedly “have shown to be by far the most complete

clonal wine in terms of flavor of all the earlier series of Dijon clones” (Marlborough Winepress, June 2010).

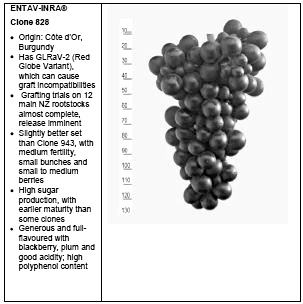

Riversun Nursery, a French licensee, reports that 828 has undergone graft compatibility trials on all the main

rootstocks used in New Zealand and has been signed off by ENTAV-INRA® for release. The nursery describes

the clone as having medium fertility with small clusters, high sugars and high polyphenol content, good keeping

qualities, and smaller bunches than 115 and 777 and slightly less productive (see copy of entry from ENTAV-INRA

® above).

In Australia, the Dijon clones are commonly referred to as “Bernard clones,” after Raymond Bernard. 828 was

imported in 2008, released from quarantine in Australia in 2010, and will be commercially available in 2015.

Nick Dry, who is in charge of Yalumba Nursery in Australia, reports the following characteristics of clone 828: medium to

high polyphenols and anthocyanin production, low to medium yield and bunch weight, medium to low berry

size, and medium bunch number; wines are balanced, aromatic (intense and fruity), round and full, and have

good aging potential.

My good friend, David Lloyd, the proprietor and winemaker at Eldridge Estate in the Mornington Peninsula region

of Australia sent me a photo of Laurent Audeguin, a Frenchman who developed the Dijon clones after Bernard.

David, who calls himself the “clone ranger,” is pouring him a glass of 828!

True Dijon 828 is newly available from the UC Davis FPS Foundation Vineyard this year according to

Adelsheim (http://fpms.ucdavis.edu/WebSitePDFs/Price&VarietyLists/GrapeNewSelectionList.pdf.) It is a

cleaned-up version of the original ENTAV-INRA® clone using micro shoot tip culture, and no longer has the

Red Globe virus. True Dijon 828 should be commercially available in California and Oregon within two years.

The Story of Upright “828” Begins with Gary Andrus

Gary Andrus graduated with a degree in organic chemistry from Brigham Young University, became a world class

downhill skier, and competed for the U.S. Olympic team. He obtained a master’s degree from Oregon

State University, and a PhD in Oenology from the University of Montpellier in France, followed by work in

Bordeaux. Andrus was a partner in a Copper Mountain, Colorado, ski resort, and when he sold his shares, he

used the profits in 1978 to found Pine Ridge Winery in Napa Valley in partnership with his wife Nancy.

Andrus was quite fond of Oregon Pinot Noir, and in 1992 he purchased a property in the Dundee Hills of

Oregon. The following year, he established Archery Summit Estate on the site, adjacent Domaine Drouhin

Oregon, and released the winery’s first vintage of Pinot Noir. A gravity-fed winery with subterranean caves was

completed in 1995.

The prestige and visibility of Oregon Pinot Noir was quickly given a boost by Andrus, who pushed for quality

and higher prices for Oregon Pinot Noir. He was a driven, competitive and talented winemaker described as

“possessing a large, boisterous personality, yet one who became laser focused in the winery,” by long time

Oregon wine retailer Jean Yates. Close friend and winemaker associate, Sam Tannahill, who worked under

Andrus at Archery Summit from 1995 to 2002, said, “Andrus had winemaking in his DNA.” Tannahill called him

“demanding, impetuous, and one who pushed boundaries.” Winemaker Josh Bergström, who was mentored

by Andrus, called him “a very complex personality, a bon vivant, and driven businessperson and winemaker.”

He was an avid outdoors man, developing a passion for fly fishing while in Oregon, and taught people to

respect nature.

Andrus introduced wood fermenters to Oregon which contributed depth, weight and silky textures to Pinot Noir,

used whole cluster ferments, and preferred a high concentration of new oak. He produced some of the highest

rated and expensive Oregon Pinot Noirs of the time. Within a few years of launching Archery Summit Estate,

he released the first Oregon premium Pinot Noir priced at $100.

Upon his divorce from his spouse Nancy in 2001, Andrus sold his remaining interest in Pine Ridge Winery and

Archery Summit Estate and retired from the wine business. Shortly thereafter, he remarried (his third spouse,

Christine, was a former wine sales associate from Colorado), had another child (he had four previous children

with his first and second wives), and reemerged with a new winery, Gypsy Dancer Estates, named after his

new baby girl Gypsy. The photo below (courtesy of Jean Yates) shows Gary, Gypsy and Christine.

He bought the Lion Valley Vineyards in Cornelius, Oregon, acquired a vineyard and set up a winery in Central

Otago, New Zealand (Christine Lorraine Estate), and began to produce Pinot Noir from Central Otago and the

Willamette Valley, releasing his first wines from the 2002 vintage from purchased and Estate fruit in 2003 and

2004. Unfortunately, financial challenges ensued and he was forced to abandon Gypsy Dancer Estates in 2006.

Andrus passed away from complications of pneumonia in 2009 at the age of 63. He will always be

remembered as a champion of Oregon wine, but one of his important legacies will be the Pinot Noir upright

clone “828” which is now widely planted in Oregon and California vineyards. One can only surmise how he

might tell the story of the lineage of the vine cutting that he brought into Oregon that become known as “828,”

so I have asked numerous winegrowers, winery owners and winemakers who knew Andrus to contribute their

first hand knowledge in an attempt to reprise this intriguing bit of history.

Andrus Brings Cuttings from Burgundy into Oregon that Become Known as “828”

There are several reliable accounts that recall when Andrus had bought property in the Dundee Hills and

laid the foundation for Archery Summit Estate in 1992-1993, he traveled to Burgundy on a number of occasions,

and brought illicit Pinot Noir vine cuttings back with him. The urban legend reported by Laurent Montalieu, the

spouse of Danielle Andrus-Montalieu, Andrus’ daughter, and Anna Matzinger, the current winemaker at Archery

Summit Estate, and others, is that the cuttings were brought back hidden inside a London Fog trench coat.

The cuttings were planted at Archery Summit Estate vineyards. One of the cuttings was found to be superior

and was eventually designated AS2 or ASW2. Between 1997 and 2001, cuttings of ASW2 went to Oregon and California

sites as well as a nursery in Sonoma County. Soon other nurseries in Oregon and California started growing

and selling it as well. Notable Pinot Noir producers in California, and a few in Oregon, bought “828” vines from

a nursery in Sonoma. There were no limits on its propagation since it did not come from ENTAV-INRA® in

France and was not imported by FPMS in California. At some point ASW2 took on the name “Dijon clone 828,”

at a time when the true 828 clone was in quarantine at FPMS in California and at ENTAV-INRA® in France,

and had never been officially released to North America due to infestation with Red Globe virus.

The details beyond these accounts become a bit murky and there are various versions of what cultivars Andrus brought to

Oregon from France. There are rumors that budwood from at least one suitcased selection other than ASW2,

also originating from Archery Summit Estate and presumably either ASW1 or ASW3, was planted in California.

It has been identified as a Pinot fin variety (possibly true 828 or even 115). How ASW2 eventually became

known as “Dijon 828” is of great interest, but unfortunately no definite clarification is forthcoming.

Ted Lemon, currently the proprietor and winemaker for Littorai in Sebastopol, California, was the original

consultant for Archery Summit Estate during its first five years of existence. Lemon laid out the vineyard blocks and chose the rootstock and clonal combinations. He told me the following.

“Gary and I made several trips to France during those days to look at clones and all things Pinot Noir. I made it

clear to Gary that I would not participate in any suitcase importations. He did those on his own, although I do

know of several trips which I suspect that he brought wood back without telling me. Some of that wood may

have been simply grabbed in a famous vineyard and some may have been specific selections. Several

selections were planted at Archery Summit including “828” and “La Tache.” In those days, the follow through at

Archery Summit may not always have been as complete as one might hope and it is possible, as often

happens, that some labeling may have been done incorrectly. Between those issues and virus questions, I

believe Archery Summit terminated the program, at least for what Gary called “La Tache.”

“I evaluated the performance of those selections over several years during my work with Archery Summit, and

subsequently sourced budwood that would become the Littorai version of the “828” plantings. We call it ‘fake

828.’ I have had several nursery people look at the Littorai version of “828,” including Pierre Marie Guillaume

of Guillaume Nursery in France, one of the premier nurserymen in that country. Lucie Morton has also looked

at it for us. The CA “828” is a fertile, upright clone, two characteristics that true 828 doesn’t share. Pierre-

Marie’s sense was that CA “828” is probably something like ENTAV-INRA® 583, an upright, but quality Pinot

Noir clone. Now where Gary grabbed it is a good question. No doubt DNA analysis could reveal the true

origin, but I am happy to grow it as CA “828.”

Lemon speculates that when Gary’s selections arrived in the United States, the labels became switched since

what was called “La Tache,” was more reminiscent of true 828. This is only educated speculation since no

work has been done to verify this.

David Adelsheim, who founded Adelsheim Vineyard in 1972 with his spouse Ginny, is an iconic figure in

Oregon wine and a respected spokesperson on Pinot Noir clones in Oregon. A vineyard person who formerly worked at

Archery Summit Estate during its founding and early establishment was later hired by Adelsheim Vineyard.

The vineyardist told Adelsheim the following version of the history of the vine cuttings suitcased into Oregon by

Andrus, which differs from Lemon’s account in a few details.

The vineyard person accompanied Andrus on trips to Burgundy where cuttings were taken from a vine in two

Domaine de la Romanée-Conti vineyards, Romanée-Conti and La Tâche, as well as Le Musigny. Those

cuttings were brought back and propagated at a nursery in Sonoma County, and subsequently planted at

Archery Summit. Apparently the Romanée-Conti and Le Musigny vines had serious virus infestation and were

eventually discarded. The La Tâche vines either had mild virus issues that were cleaned up at the Sonoma

nursery or were clean enough without those measures. The progeny of the La Tâche cutting is now called AS2

or ASW2 and is planted at Archery Summit as well as numerous other Oregon and California vineyards,

including Adelsheim Vineyard.

Adelsheim confirms that ASW2 is a Pinot droît selection that grows upright, and in a non hedged vineyard, can

easily be distinguished from all other normally used Pinot Noir clones which fall over. It does not have Red

Globe virus, and he doubts it ever did have that virus.

Anna Matzinger joined Archery Summit Estate as an assistant winemaker in 1999, and became the winemaker

upon the departure of Sam Tannahill in 2002. Leigh Bartholomew is Archery Summit’s viticulturist who is

familiar with the winery’s records. Their version of the provenance of ASW2 is as follows. “Urban legend has it

that Andrus returned from a trip to France in the mid-1990s with three Pinot Noir cuttings which were

propagated in a demonstration vineyard at the winery as well as other estate vineyard sites. The clones made

the trans-Atlantic journey sewn into the hem of a London Fog coat. Given that the owner of the coat had a flair

for the dramatic, what actually transpired is anyone’s guess. The cuttings were known in-house as ASW1,

ASW2, and ASW3. ASW2 was preferred over time and was subsequently sold as budwood. ASW2 has not

tested positive for Red Globe.”

Sam Tannahill could not speak to the provenance of “828” (ASW2) at Archery Summit Estate (he said he did

not join the winery until 1995 and was not around when the cuttings were secured), but did confirm that it was upright growing. He reported that a DNA test was performed that confirmed that ASW2 was Pinot Noir (they

thought it might be Gamay Beaujalois, another upright selection). When he was the winemaker at Archery

Summit, there were four “interesting” clones: “true” 828 (supposedly from Guillaume in France), a La Tâche

clone, a Romanée-Conti clone, and a Musigny clone. He is unclear about which, if any, of these clones are still

in the ground at Archery Summit Estate. Matzinger told me that Archery Summit Estate currently has about 5

acres of ASW2 out of a total of 110 acres currently in production.

John Haeger has written two well-researched books which have become standard references for reliable

information on Pinot Noir, and particularly Pinot Noir clones: North American Pinot Noir (2004) and Pacific Pinot

Noir (2008). In the latter book, he weighs in on the history of Archery Summit Estate and the lineage of ASW2.

Haeger visited Archery Summit Estate in 2000 and talked with Andrus. The ASW designations were not

discussed and Haeger had the impression that they did not yet exist. None of the selections were identified to

Haeger as 828. Haeger’s discussions several years later with Leigh Bartholomew revealed the ASW

designations. Something reportedly from Romanée Conti was designated ASW1; something said to have

originated from La Tâche was designated ASW2; and something said to have come from Le Musigny was

designated ASW3. Presumably, the AS designations eliminated the need to say what the Burgundian source

was for each. The ASW2 proved to have the least virus issues and at some point ASW1 and ASW3, which

were heavily infested with viruses during trials at Argyle, were destroyed.

According to Haeger, ASW2 was first established in a demonstration block adjacent the Archery Summit Estate

winery, followed by plantings at Block 1 at Renegade Ridge and Block 21 at Red Hills and Looney. “He

(Andrus) was not at all circumspect or reticent about the sources of the selections he had personally imported

illegally and planted on Renegade Ridge. In fact, that is how Renegade Ridge was named, or at least so Gary

said: the spot where he planted the objects of his “renegade” activity. At that time (2000), the selections at

Renegade Ridge were known for their sources: La Tâche, La Romanée-Conti and Le Musigny. None of the

selections were identified to me as 828." 828 was not a particularly hot topic at the time and Haeger did not

delve deeply into it. Haeger confirms the upright growth habit of ASW2.

Haeger approaches the question of how ASW2 became known as Dijon 828 as follows. “For reasons that are

not entirely clear, but apparently stem from conversations Andrus allegedly had with some of the vintners and

growers who obtained cuttings, some ASW2, propagated in other vineyards, and redistributed by nurseries,

has come to be known as Dijon (or CTPS) 828, even though it almost certainly is not. As this incorrect identity

has become clear, some growers have begun to call it faux-828 instead.”

Haeger recalls that Bartholomew found no evidence in the Archery Summit Estate records of any vine cuttings

provided to third parties ever identified by Archery Summit Estate, in writing, as 828. “This identification seems

to have been made by third parties, though some of these parties say that Andrus told them so. It’s hard for

me to believe that Gary actually thought any of his suitcase selections was 828. None of the source vineyards

in France were planted to known clones as far as I know.” In deference to that remark, remember that Ted

Lemon reported that he believed Andrus grabbed cuttings from both famous vineyards and specific selections.

Adelsheim has bought “828” from Sunridge Nursery in California and planted it side-by-side with ASW2 taken

from Archery Summit. They look identical. He plans to make wine from them separately from the 2012

vintage.

The question of how ASW2 became known as “828” will probably never been answered. We know that ASW2

made very respectable wine. Adelsheim notes, “At some point after 2000, he (Andrus) started offering barrel

samples of a wine made from “828.” It tasted good. We had no reason to doubt that he had brought it in to the

United States in a suitcase.” Dijon clone 828 was not in the United States, but when initially released in

France, 828 quickly became a popular clone in Burgundy and received a grade of “A” from its “potentielle de

production,” according to Adelsheim. Stateside Pinot Noir producers were alert for the next “hot” Dijon clone

(“Make mine Dijon please” was the era’s catch phrase), and reports on 828 from France were enticing.

Matzinger said she does not know exactly how ASW2 became known as 828 but she expressed to me a

plausible explanation. “Perhaps Andrus knew it to be 828, thought it to be 828, or simply wanted it to be 828.”

Montalieu, like many others I spoke with, reiterated that he had no idea how ASW2 became designated as 828,

but said that 828 was a hot clone in Burgundy at the time, at the forefront you could say, and Andrus could

have assumed he had 828. He may have attempted to procure true 828, but unknowingly got something else.

Dick Erath told me, “Knowing Gary, he probably thought he had the real thing.” It does not appear that potential threats from the French deterred Andrus, at least initially, from naming the cuttings he brought into the country

illegally. One could speculate that for someone who was intent on building on the visibility of Archery Summit

Estate and Oregon Pinot Noir, Andrus may have seen the chance to be the first to have clone 828 as a way of

attracting admiration from his colleagues, a feather in his cap so to speak.

Matzinger reports that after Andrus’ retirement from Archery Summit Estate in 2001, any budwood sold by Archery Summit Estate was

labeled ASW2 and previous purchasers were notified of the name change. Nurseries now list and offer "828" in

their catalogues, but clearly inform buyers that it is not the real Dijon 828 clone.

Faux “828” Takes On Other Names and is Characterized

ASW2 has taken on many tags over time. I have already mentioned faux “828,” suitcase “828,” and CA “828.”

Some call it the “Viagra clone” because of its upright growth. Others term it the “Don King clone” for the same

reason. Joel Myers likes to reference it as the “black dog clone,” because it doesn’t have the pedigree (not

certified) of a Black Labrador Retriever which is a good hunter, but is just as good a producer. It has also been

named the “gumboot clone,” for obvious reasons.

Winegrowers and winemakers who have worked with faux “828” generally agree it is a good producer and can

perform well at sites with marginal climate. Haeger points out that most Pinot droît selections are prolific

bearers but the grapes are often of mediocre quality. Jean-Michel Boursiquot, ampelographer and former

director of ENTAV, concurs and has said, “The more upright clones are considered to produce inferior wines.”

Despite these incriminations, some Pinot droît cultivars, including faux “828,” have performed well in the United

States.

Ted Lemon has described his experience with CA “828” as positive. “Once it is cleaned up of viruses (what came to

Oregon had other viruses besides Red Globe), it is a productive, vigorous vine which performs well under

challenging situations like that found in the Sonoma Coast. It tends to produce well and require some thinning.

Set is not a sure thing and there can be wide variation from year to year. Color is generally good and it tends

to go through veraison late and ripen slightly later than the classic Dijon selections.”

Peter Cargassachi, winegrower and winemaker in Sta. Rita Hills, California, said, “The "828" Pinot droît clone

produces long, loose clusters and resembles clone Mariafeld UCD 23 which is also a Pinot droît clone.”

Jason Drew, of Drew Family Cellars in Elk, Mendocino County, is currently working with two vineyards that

have "828" blocks planted, but the two "828" blocks have obviously different morphology and both are planted on

101-14 rootstock. One selection he works with has small berries and small clusters with shy yields. The

selection typically provides wine with excellent richness and depth. The other "828," which he is

guessing came from Archery Summit, is markedly different concerning the growing stature of the vines. The

berries are significantly large and the clusters are sometimes twice the size of the other 828. The vines are

more vigorous and grow more erect with significant apical dominance. The wine from this "828" has good

intensity but does not have as much tannin and mouth feel as the smaller 828 offers. The more vigorous

version is slower to ripen and has nice mature flavors but is more feminine and delicate without the depth that

the smaller version has. Jason notes, “I would think about blending the faux "828" if I wanted brighter flavors

and lighter tannins. Conversely, I would use the smaller 828 for denser qualities and richer tannin. Ironically,

they would make a very nice pair if blended. Then and only then could you call it ‘one’ 828 instead of two.”

In the photos that follow, taken from California and Oregon vineyards just before harvest, the upright growth

habit of faux "828" is evident. The clusters are long and large and the upright shoot growth helps keep the

clusters hanging free and easily visible. As the clusters take on sugar at the end of harvest, they tend to fall

and this is also visible in the photos, particular the photos from Rosella’s Vineyard.

ASW2 at Archery Summit Estate, Dundee Hills, courtesy of Anna Metzinger

ASW2 at Archery Summit Estate, Dundee Hills, courtesy of Anna Metzinger

Faux “828” at Inman Family Winery, Olivet Grange Vineyard, Russian River Valley, courtesy of Kathleen Inman

Faux “828,” typical giant cluster, 3 days before harvest, Inman Family Winery, Olivet Grange Vineyard, Russian

River Valley, courtesy of Kathleen Inman

Faux “828,” Rosella’s Vineyard, Santa Lucia Highlands, courtesy of Adam Lee

The Wine from Faux “828”

Faux “828,” like many clones, has performed inconsistently depending on the site at which it is planted. As

Haeger points out in North American Pinot Noir, “So for Pinot Noir, despite all the passion for clones and clonal

selection, the mantra remains the old adage about real estate; location, location, location.” Noted winemaker

Merry Edwards, upon establishing her Coopersmith Vineyard on the Laguna Ridge near Sebastopol in the

Russian River Valley, chose to plant 50% of the former 9.5-acre apple orchard in 2001 to faux "828" clone

obtained from Archery Summit Estate. The clone turned out to be a poor match for the terroir, and was

converted to Mount Eden UCD 37 by 2008. Only a few miles northeast, faux “828” has proven to be a stalwart

clone at Inman Family Wines Olivet Grange Vineyard for Kathleen Inman.

The truth, as expressed by viticulturist Joel Myers, is that with faux “828,” “Some like it and some don’t.” Most

agree that it produces intensely flavored wine with very good color. Winemaker Peter Cargasacchi describes

his wine from faux “828” grown in the Sta. Rita Hills as being “dark, succulent, with blackberry and dark cherry

character.” Chad Melville, winemaker at Melville Vineyards and Winery, also in the Sta. Rita Hills, has faux “828” planted both directly

from Archery Summit Estate and Merry Edwards. “They are different visually on the vine and as a wine. The

faux “828” is planted in very sandy soil and has a very pretty lifted aromatic profile of dried roses, dried herbs

along with an elegant mouth feel. The Merry Edwards "828" is planted in a heavier loam and is darker and

richer.”

Eric Hickey is the winemaker at Laetitia Vineyard & Winery in Arroyo Grande Valley which has a little more than

9 acres of an “828” Pinot droît selection planted. He told me, “The Laetitia flavor profile is known for bright red

fruit characteristics, but “828” is much more of a dark, black fruited, slightly more tannic Pinot Noir, which is a

nice blend to our portfolio. “828” is one of ten Pinot Noir clones that we grow and we release an “828” single

clone wine because many of our house wines are blends of these clones and we try to highlight each clone so

that patrons can learn what these clones bring to the blends and what they are like when grown at Laetitia.”

Adam Lee, winemaker at Siduri Wines in the Russian River Valley, works with vineyards throughout the state of

California and even Oregon, said, “I think it is a bit boring truly. Reminds me of 777 in that it makes a good

middle part of the wine but needs stuff around it to make it interesting. Generally, it ripens later than 777, has

thicker skins (a bit like Martini in that way, though not quite as extreme), and seems to be finely flavored, but

nothing I would recommend anyone plant.”

Stewart Johnson, who farms Kendric Vineyard in Marin County, has faux “828” planted and found it to be the

easiest clone to farm because it grew straight up through the trellis wires with little need for shoot positioning.

It set a big crop and tended to ripen late. He vinified it separately in the past but “the color was pretty light, it

did not show a ton of character, and for me, it was just a filler.” He is not a fan.

Paul Lato, proprietor and winemaker for Paul Lato Wines in Santa Maria Valley only uses “828” in wines for his

consulting client, Hilliard Bruce. From his limited experience, he finds the clone simple, lacking in complexity

and unexciting. He does not envision himself seeking any vineyards to obtain this clone for himself.

Michael Sullivan, winemaker for Benovia Winery in the Russian River Valley told me the following about faux

“828.” “I have worked with the faux “828” and have been more or less happy with the results. It tends to have

more structure (more tannin) with higher acid and color than many Dijon selections. That being said, it is not a

stand-alone clone but a good blender. I also find that I have to thin the crop heavily with faux “828,” as the

clusters are large and the vines can overproduce.”

Most winemakers agree that faux “828” performs best as part of a blend with other clones. For that reason,

single clone wines from faux “828” have rarely been released commercially. I know of examples from Buena

Vista, Del Dotto, Halleck, Laetitia and Melville Vineyards and Winery in California, and Duke’s Family Vineyards

in Oregon. The following two wines were reviewed by me recently. Both wines were pleasant, fruity, and

relatively simple with noticeable tannin and short finishes.

2009 Laetitia Clone 828 Arroyo Grande Valley Pinot Noir

13.9% alc., $32.

·

Medium reddish-purple color in

the glass. Opens slowly in the glass, revealing aromas of black cherries, black raspberries, prune, spice and

oak. Soft and smooth on the palate, with moderately rich flavors of dark red cherries and berries with a topcoat

of toasty oak. Nicely balanced with firm, but well-integrated tannins. Good.

2006 Halleck Clone 828 Sonoma Coast Pinot Noir

14.2% alc., 266 cases, $55. Sourced from a vineyard

near Annapolis. Aged in 30% new French oak barrels.

·

Moderately light reddish-purple color in the glass.

Aromas of black cherries, spice and balsam. Flavorful, mid weight, earth-kissed black cherry core with subtle

smoky oak in the background, all wrapped in firm tannins, offering a soft mouth feel, and finishing with a

cherry-fueled note. Good.

Summary

* Undocumented grapevines have been brought into the United States from France since the mid-1800s.

Noted winemaker, Tony Soter, said in the past, speaking from a California prospective, “Among men and

women who consider themselves Grail-seekers of Pinot Noir, it is understood that smuggling is part of the

tradition.” In Oregon, because Oregon State University had its own import permit and was willing to bring in

anything winegrowers in Oregon wanted, there was virtually no suitcase smuggling of Pinot Noir clones.

According to Adelsheim, “I have heard only of the Coury rumor and the Andrus selections; nothing else.”

* Gary Andrus, the founder of Pine Ridge Winery in Napa Valley, Archery Summit Estate in the Willamette

Valley, and Gypsy Dancer Estates in Central Otago and the Willamette Valley, smuggled budwood into the

United States from France in the early 1990s that purportedly came from famous Burgundian vineyards. The

true origins of that budwood will never be known.

* The grapevine cuttings that Andrus brought in, sewn into a London Fog coat as urban legend would have it,

were propagated at Archery Summery Estate. One particular cutting, termed ASW2, proved to be the best

performer and the least virused. It was a Pinot droît variety that produced good wine.

* Beginning in 1997, cuttings from ASW2 were widely distributed to wineries and nurseries throughout Oregon

and California. Since the selection was not certified, there were no restrictions on its propagation. At some

point, and for reasons that remain a mystery, ASW2 became known as clone “828.” The true Dijon clone 828

was quarantined in France and at UC Davis because of Red Globe virus. ASW2 never tested positive for Red

Globe virus.

* True Dijon 828 is newly available from the UC Davis FPS Foundation Vineyard this year. It is a cleaned-up

version of the original ENTAV-INRA clone, and no longer has the Red Globe virus. Since 2001 when Andrus

sold his interest in Archery Summit Estate, all budwood sold from that source are labeled ASW2 to distinguish it

from “828” and buyers are notified of the name change.

* Currently, the viticulture trade refers to ASW2 as faux “828” or upright “828.” It will be of interest going

forward to see what ASW2 will be called as true 828 becomes available in the United States.

Postscript

Laurent Deluc, Assistant Professor in the Department of Horticulture at Oregon State University (OSU), is

currently undertaking long-term projects to sequence several Pinot Noir clones, working collaboratively with the

Center for Genomic and Research Biocomputing facilities at OSU. Currently, OSU has the laboratory workflow

and the bioinformatics platform to analyze expression data using RNA Seq technology. It is hoped that ASW2

can be integrated into this large initiative to fully map several Pinot Noir clones. This would, of course, reveal

the true origin of ASW2. Stay tuned.

Appendix

The word clone is from the Greek word for twig. Clones are separate vines that are genetically identical to a

mother plant. They have the same growth, habit, flavors and ripening time as the vine they come from. Clones

are propagated asexually by taking cuttings or grafts from another vine. Seeds are not suitable for propagation

since after pollination, new seeds are not genetically identical.

The clone of Pinot Noir will determine the flavor profile of the resulting wine along with the effects of terroir such

as soil and microclimate. Clones will have differences in bud break, time of ripening, cluster architecture,

yields, size of berries, fruit quality and other characteristics.

Clones are registered by FPS at UC Davis and certified by ENTAV (Etablissment National Technique pour

l’Amélioration de la Viticulture) in southern France. A certified clone is propagated from the same parent plant,

tested for specific viruses, and kept clean. These certified cloned vines are then named or numbered and

propagated on site and cuttings made available to nurseries.

Cuttings taken from different vines that do not have a common parent, and thus have a diverse genetic heritage, are referred to as selection

massalle or mass selection, or simply selection. For example, none of the so-called heritage or suitcase

“clones” of Pinot Noir planted in California are truly clones. They originally represented multiple cuttings taken

from several vines in a vineyard and thus represent a cultivar or selection. An example is the so-called Swan

“clone” of Pinot Noir which technically should be termed the Swan selection. The Swan selection was brought

to the United States by Paul Masson who reportedly took budwood from Romanée-Conti and planted it in

Saratoga, California. His successor, Martin Ray, planted a new vineyard with cuttings taken from Masson’s

vineyard at what became known as Mount Eden. Joseph Swan, in turn, took cuttings from Martin Ray’s

vineyard, planted them in the Russian River Valley, where over time others took Swan’s budwood and

propagated them throughout California.