Grapevine Red Blotch Disease Threatens Pinot Noir & Other Grapes

As vintners recover from a harried, compact 2014 harvest, and concern themselves with the vestiges of a

continuing drought, there is apprehension about a new threat. An aggressive virus producing Grapevine Red

Blotch Disease (GRBV) is now widespread in California vineyards of the North Coast, Central Coast and San

Joaquin Valley of California.

The virus, a member of the geminivirus family, Geminiviridae, carries the proposed name GRBaV, or

“Grapevine Red Blotch-Associated Virus,” to describe its association with the grapevine and red blotch disease.

Jim Wolpert, a UC Davis-based Cooperative Extension viticulturist and Mike Anderson, a UC Davis viticulture

researcher, first discovered the disease in 2008 at UC Davis’ Oakville Experiment Station in Napa Valley.

Cabernet Sauvignon vines grown there showed leaf changes that resembled those caused by leafroll virus, but

the vines tested negative for that virus.

The GRBaV virus has probably been present in California vines before this discovery, but its similarity to

grapevine leafroll disease delayed identification of the disease. Currently, a lack of education, the confusion

with leafroll, the possible emergence of a more virulent strain of GRBaV, and the failure to institute practices to

curtail it, have led to the spread of GRBV.

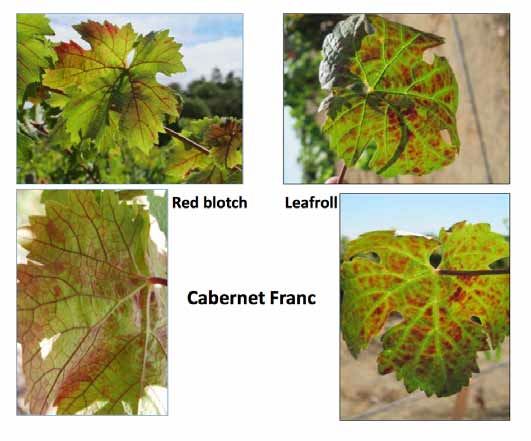

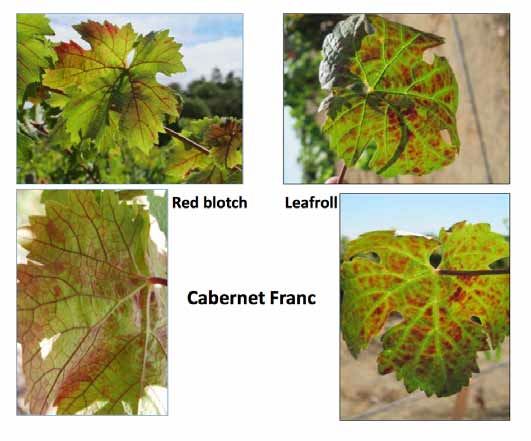

According to the University of California Integrated Viticulture site at www.iv.ucdavis.edu/viticultural_information, symptoms of red blotch disease appear in late August through September as irregular

blotches on leaf blades on the basal portions of shoots. The changes resemble leafroll disease, but the leaf

margins in GRBV do not roll downward, and the leaf veins in GRBV turn partly or fully red while leafroll has

green veins. The photos below are from a report titled Red Blotch-Research Status by Deborah Fravel of the

USDA Agricultural Research Service: www.ngwi.org/files/documents/Presentations_May2014/D_Fravel_52214.pdf. The top two photos are of GRBV in Pinot Noir and the bottom photo compares GRBV to

leafroll.

The DNA virus, GRBaV, was identified by Maher Al Rwahnih, a researcher at UC Davis Foundation Plant

Services (FPS), an expert in DNA sequencing technology, and Mysore Sudarshana, a U.S. Department of

Agriculture researcher in the UC Davis plant pathology department in 2012, and confirmed subsequently by

others. Rwahnih and cohorts published a report on GRBaV in Phytopathology: www.apsjournals.apsnet.org/

doi/abs/10.1094/PHYTO-10-12-0253-R. A DNA-based polmerase chain reaction (PCR) assay has been

developed to detect it in any tissue of the vine - leaf, petiole, clusters, or dormant canes at any time of the year.The virus is discoverable before the onset of symptoms in the affected grapevine.

The transmission methods of red blotch disease are not clearly defined although it appears that GRBaV can be

spread by grafting and propagation, and a possible vector, the Virginia creeper leafhopper, has been identified.

There are conflicting reports on spread in vineyards by pruning and harvesting, and some growers have

already resorted to sterilizing pruning shears with bleach between each cut as well as sanitizing other

mechanical equipment. If such a step in pruning, hedging and harvesting proves to be necessary, the cost of

farming grapevines could easily double.

The effects of GRBD are much more devastating than leafroll. Sugar levels in grapes grown on vines affected

by Red Blotch can suffer a Brix reduction of up to 4º to 6º, much more than is seen with leafroll-diseased

grapevines. In addition, ripening is delayed, color is reduced in red grapes and wines, and phenolics are

disturbed. In essence, once a grapevine is infected and symptoms appear, the grapevine cannot produce

commercially useful grapes.

There are also conflicting reports on the effect of GRBD on the longevity of vines, but the threat of rapid spread

of the disease within a vineyard and the consequences make this determination almost irrelevant. There are

some reports that vine death is accelerated.

Cornell plant virologist, Dr. Marc Fuchs, is at the forefront of GRBD research. In late 2013, he conducted a

Red Blotch speaking tour of Northern California and his UC Davis seminar can be found on the University of

California UC Integrated Viticulture website at www.iv.ucdavis.edu/?uid=284&ds=351. A March 27, 2013

webinar is also available on Red Blotch.

GRBD does not discriminate, affecting many red grape varieties including Pinot Noir, as well as white grape

varieties and even table grapes. The symptoms can be more challenging to identify in white grape leaves

such as the example show below from a Riesling vine (photo also from Deborah Fravel report cited above).

There is currently no cure for GRBD. Dr. Fuchs recommends that symptomatic vines be tagged in the fall and

removed during the dormant season when insect activity is very low or absent. If greater than 25% of vineyard

is affected, the entire vineyard should be replaced - a scary thought for winegrowers. Some vineyards in the

North Coast have already been torched following this last harvest.

At UC Davis FPS, GRBaV has not been detected at the new Russell Ranch Foundation Vineyard, and there

has been a low incidence discovered at the Classic Foundation Vineyard.

It is interesting to speculate that the 3-year drought and other climate changes have contributed to the

emergence of a more aggressive or at least opportunistic GRBaV virus. We know that grapevines as well as

all plants have disease resistance mechanisms (some of which are also common in animal and human

immune systems) that allow the plant to tolerate certain viruses within and show little disease damage from

those pathogens. The interaction of the plant, a pathogen and the environmental conditions is known as the

disease triangle. A significant change in the environment can tip the scale in favor of a pathogen and disease

damage may appear.

I asked noted winegrower and winemaker, Ted Lemon, to comment on my speculative thoughts. “There is no

doubt that viruses can remain dormant in grapevines for many years. And, like humans, I would expect that

stress, including drought, could favor expression of the virus. As for the mechanism(s) that induce expression,

that is a million dollar question.”

Ted went on to talk about virus detection and management in grapevines in general. “From a viticultural point

of view, most of our leading researchers and government agencies take the approach of somehow trying to

‘guarantee’ that plant material will be virus free. They have been singing this siren song for decades. Our

plant material has never been virus free. It is clearer than ever that most of the nursery sources and FPS are

full of virus.” This comment relates directly to GRBaV since it has been found that micro-shoot tip cultures

work effectively in only 25% of Red Blotch-infected grapevines. Clearly, Ted advocates “more systems and

ecological research, and less emphasis on cutting edge virology research.”

In summary, Ted concludes, “Our goal for people and plants ought not to try to make them virus and disease

free, but to create vibrant, healthy ecosystems (be they on the farm or in the home) where balance prevents

disease associated with virus expression. In the case of humans, the moral question pushes us to try to insure

that no one suffers from virus-induced disease and we err on the side of too much medicine. In the plant world,

we can more easily accept the risk that a percentage of plants fail if this creates better health in the overall

population.”

Thanks to vintner Claude Koeberle of Soliste Wines for piquing my interest in this subject and providing references.