Research Published in 2018 that Supports Light to Moderate Drinking as a Healthy Lifestyle Choice

“The message from science is: Have a drink if you want. And two won’t kill you.”

Terence Cocorian, Financial Post

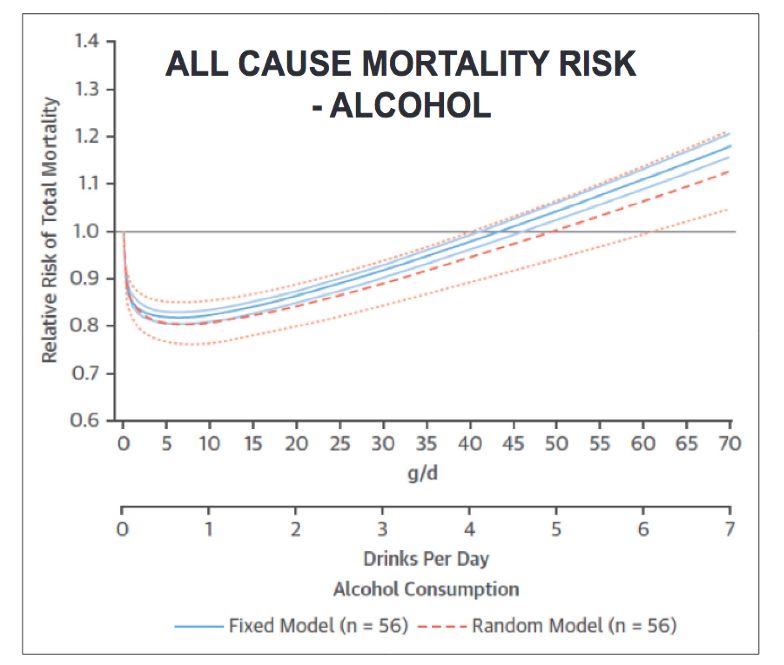

Mortality

The International Meeting on Alcohol and Global Health was held September 25, 2018 in Leuven, Belgium.

Important studies by professors and scientists from across Europe reported at this meeting were published in

the October 2018 AIM Digest. Professor Giovanni de Gaetano from Italy presented a talk on the J-shaped

curve that is often used to describe the relationship between alcohol consumption and total mortality. As the

chart below demonstrates, 1-2 drinks a day or light-to-moderate drinking represents optimum exposure

to alcohol while the increased risk in life-long drinkers or heavy drinkers reflects the consequence of

sub-optimal exposure.

Professor Gaetano pointed out that the pattern of drinking is important. A drink a day with food is protective

while a similar amount on one or two occasions negates the J-shaped curve. When excluding the effect of

confounding factors such as diet, lifestyle and socioeconomic status, the J-shaped curve has been

demonstrated in multiple studies over the past twenty years. The J-shaped curve has also been verified for

cardiovascular disease. The benefits of drinking shown by J-shaped curves apply mainly to men over 40

and postmenopausal women when the risk for heart disease increases.

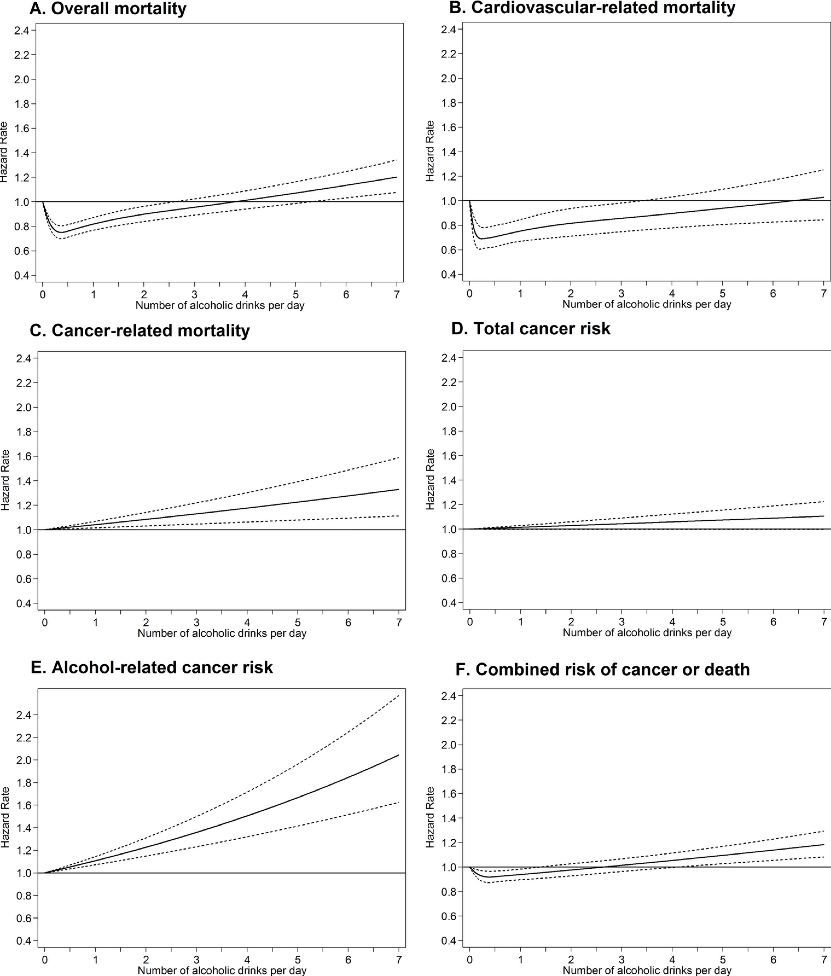

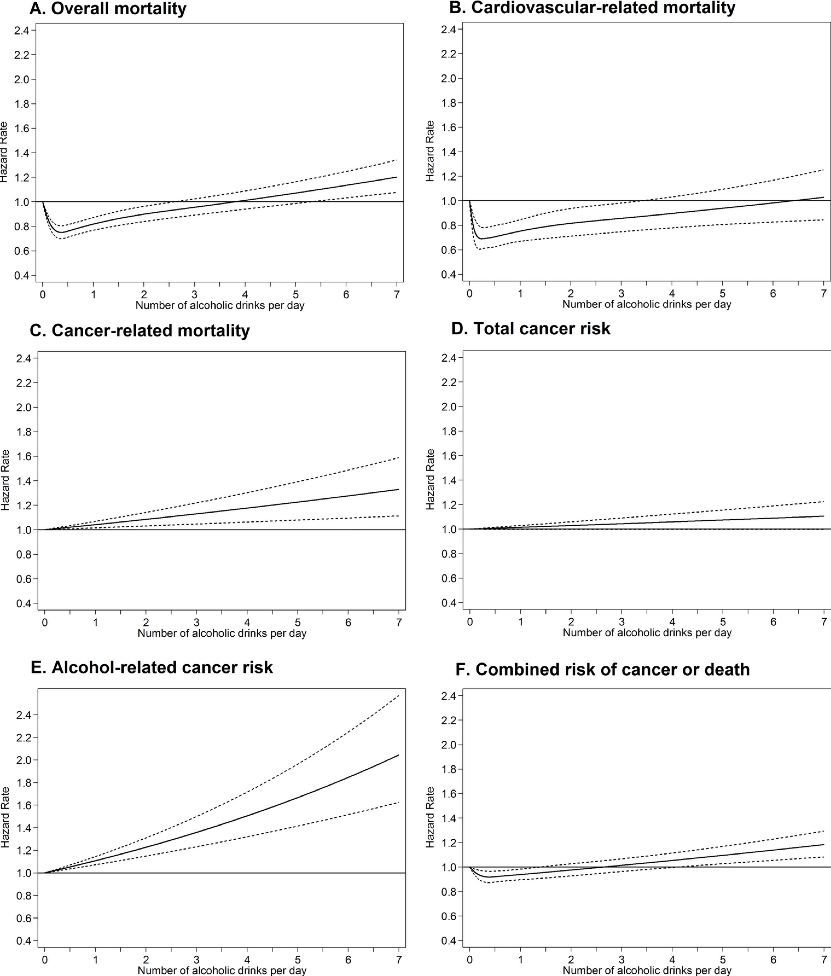

A very important study appeared in July 2018 in PLOS Medicine affirming the J-shaped curve for mortality.

99,654 adults aged 55-74 participating in the United States Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian (PLC)

Cancer Screening Trial were studied. The IFSAR critique indicated that this was a well-done analysis and

showed essentially for the first time in a single study how the beneficial effects of light and moderate drinking

on cardiovascular disease and total mortality exceed the slight increase in cancer risk for alcohol consumption

at this level. In other words, while even light-to-moderate drinking may be associated with a slight

increase in the risk of certain cancers, such drinking still favorably affects the overall risk of mortality in

older adults. The results indicated that intakes below 1 drink per day were associated with the lowest risk of

death.

An analysis using data from the Nurses’ Health Study (1980-2014) and the Health Professionals Follow-up

Study (1986-2014) was published in the journal Circulation in April 2018. Five low-risk factors were studied

including never smoking, body mass index of 18.5-24.9 kg/m2, greater or equal to 30 minutes of daily

moderate to vigorous physical activity, moderate alcohol intake, and a high diet quality score (upper 40%). The

projected life expectancy at age 50 among female Americans with all 5 low-risk factors was 14.0 years longer

compared with those with zero low-risk factors, and for men, the difference was 12.2 years. This study confirms

the results of many other cohort observational studies that conclude that adopting a healthy lifestyle including

moderate alcohol consumption could substantially reduce premature mortality and prolong life expectancy in

U.S. adults.

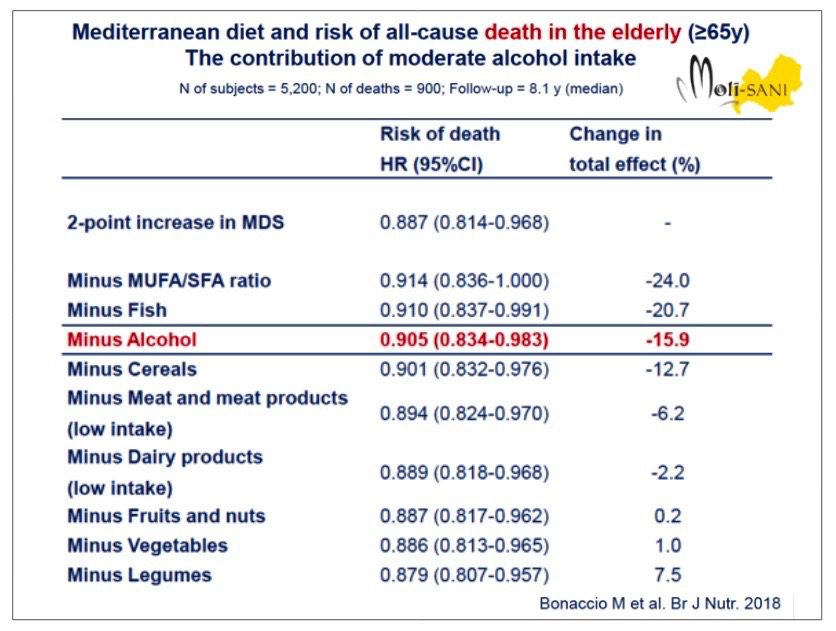

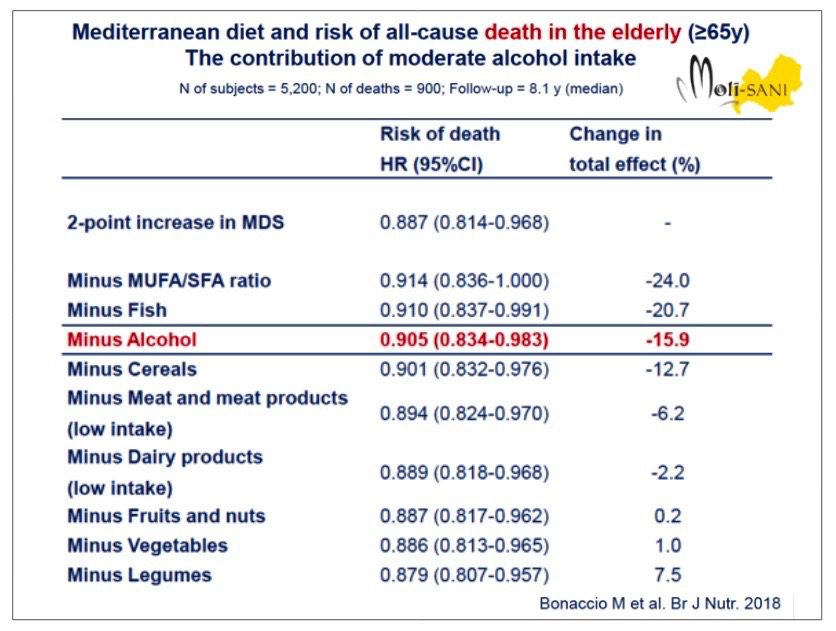

A prospective cohort study and meta-analysis published in the British Journal of Nutrition in October 2018

showed that closer adherence to the Mediterranean diet (MD) was associated with prolonged survival in elderly

individuals equal to or greater than 65 years. This suggests the appropriateness for the older person to adopt

or continue the MD to maximize their prospects for survival. If alcohol is removed from the MD, the

protective effect is reduced by 15%.

The 90+ Study at the University of California Irvine Institute for Memory Impairments and Neurological

Disorders (UCI MIND) has followed 1,600 elderly adults since 2003 through twice-yearly evaluations.

Consuming two glasses of wine or beer per day was associated with a 15 percent reduced risk of premature

death compared to abstainers. Regular exercise, social and cognitive engagement, moderate coffee

consumption, having a hobby, and being overweight in the 70s also led to a longer lifespan. This study and

another study on “Super Agers” that looked at people in their 80s were presented at the American Association

for the Advancement of Science in February 2018. The conclusion was that those who drank a couple of

glasses of wine or beer a day were more likely to live longer compared to abstainers.

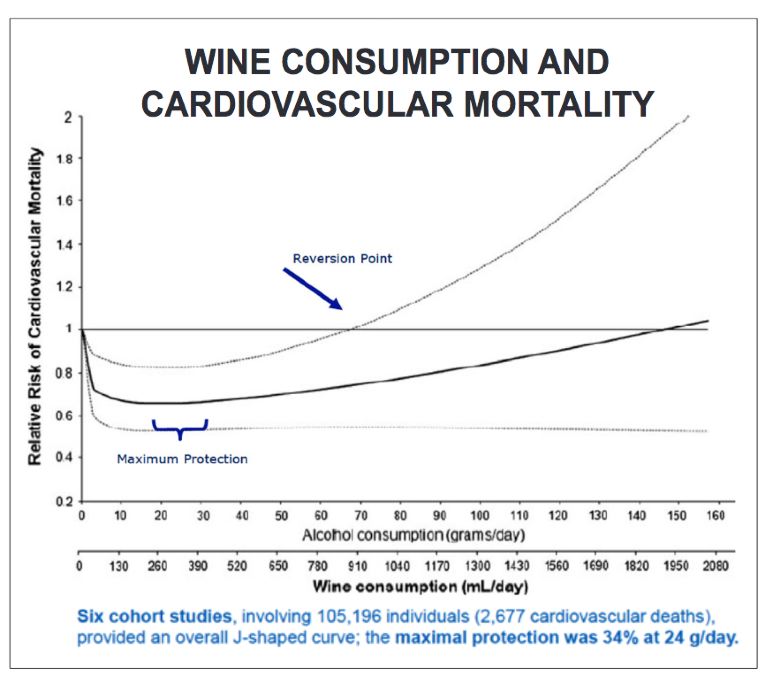

Cardiovascular Disease

According to a study from the American Heart Association released in January 2019, nearly half or 121.5

million Americans dealt with heart or blood vessels disease as of 2016. The study noted that death from

cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the number one killer of all Americans, women as well as men, rising from

more than 836,000 in 2015 to more than 840,000 in 2016. CVD is also the leading cause of death globally.

CVD is comprised of coronary heart disease, heart failure, stroke and a high blood pressure reading now

defined by the American Heart Association as a reading of 130/80 mm Hg, an increase from the previous

definition of 140/90 mm Hg. Over 20 years of research has shown that for many people, moderate

consumption of alcohol can protect the heart but the reason for this is still unclear. Studies to date have not

proven that alcohol or polyphenols in wine such as resveratrol, quercetin and ellagic acid are most important for cardiovascular health benefits.

In 2018, the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), part of the National Institutes of

Health (NIH) began a 10-year, $100 million dollars Moderate Alcohol and Cardiovascular Health (MACH) trial

that was aimed at removing the debate on whether drinking lowers the rate of heart disease. The plan was to

study 7,800 participants older than 50 living on multiple continents, of both sexes, and who were at risk for

CVD. Heavy drinkers were excluded. The controlled study assigned participants to two groups: one group was

to consume one alcoholic drink every day for six years and one group was to abstain from alcohol every day

for six years. The study was halted on June 15, 2018, because it was revealed that funding for the study came

from the alcohol industry through the nonprofit Foundation for the NIH. There were also a number of criticisms

of the design of the study, including too short a period of study, not enough enrolled participants and the

exclusion of women at high risk for breast cancer.

An analysis of Norwegian population-based health surveys published in PLOS Medicine in January 2018 found

that moderately frequent alcohol consumption, that is, 2-3 times per week, was associated with a lower risk of

CVD compared to those who infrequently consumed alcohol (less than once per month). The benefit was more

pronounced among those with a higher socioeconomic position. Very frequent drinking (4-7 times per week)

was associated with a higher risk of death from CVD but only among those with a low socioeconomic position,

presumably because of lifestyle differences. Those in the middle and high socioeconomic categories were not

at higher risk. Binge drinking was associated with an increased risk of CVD in all groups regardless of

socioeconomic position.

Researchers at the University of Athens and Harokopio University in Athens reported in the journal Metabolism

in June 2018 a meta-analysis of 76 past scientific reports about wine’s acute and long-term health effects. This

study suggested that increased levels of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) or “good cholesterol,” was due mainly

to ethanol found in any type of alcoholic beverage, not just wine. The body’s blood clotting system was

positively affected by wine’s micro-constituents that decrease platelet aggregation, and by alcohol in general by

lowering levels of fibrinogen. The study’s authors concluded that wine appears to have a positive effect

on cardiovascular health but the exact sources of these benefits, that is alcohol or polyphenols or

otherwise, could not be determined and more controlled studies are needed.

A meta-analysis of six cohort studies using individual participant data reported in the BMC Medical Journal in

August 2019 by United Kingdom researchers found that those who consistently drank moderately (12 standard

U.S. drinks per week for men or 8 for women) had a lower risk of developing coronary heart disease than

inconsistent drinkers, nondrinkers (woman only) and former drinkers with former drinkers having the highest

risk (see chart below). The elevated risk among inconsistently moderate drinkers was only present in

participants older than 55. The researchers concluded that the findings supported the notion of a

cardioprotective effect of moderate alcohol intake relative to non-drinking, but the consistency of

alcohol consumption over time appeared to be an important modifier of this association. The six studies

reviewed were observational so the results do not prove the direct effects of drinking patterns on CVD.

Researchers from Harvard and Italy reported on the prospective results from the Moli-sani cohort study of an

adult Italian population in the Addiction Journal in December 2018. The authors of the study looked at the

relationship between alcohol consumption and the risk of hospitalization and found that those who consumed

roughly one drink per day endured fewer hospital visits compared with those who drank more and those who

did not drink at all. Also, those who drank 1-12 grams of alcohol per day had a lower rate of CVD compared to

lifetime abstainers and former drinkers.

Brazilian researchers in partnership with scientists at Stanford University reported in the journal Cardiovascular

Research in June 2018 the results of a study of an ex-vivo model in mice designed to see the role of aldehyde

dehydrogenase 2 (ALDH2) in cardioprotection. ALDH2 is a mitochondrial enzyme that neutralizes

acetaldehyde, an intermediate product from ethanol digestion. The researchers had previously demonstrated

that acute ethanol administration protects the heart from ischemia/reperfusion injury through activation of

ALDH2. This study suggests that moderate exposure to ethanol causes minor stress in heart cells but not

enough to kill them, intracellular signaling is reorganized as a result, and heart cells eventually create a

biochemical memory to protect against stress (preconditioning). 50% of East Asians with the ALDH2 gene

mutation cannot properly metabolize ethanol, causing high levels of acetaldehyde and exposing them to

maximum heart damage. In those with a normal ADH2 gene, heart damage can be exacerbated if a large

amount of alcohol is consumed as in binging since the excessive production of acetaldehyde makes it difficult

for ALDH2 to effectively neutralize all of it. In summary, this study suggests that low levels of acetaldehyde are

cardioprotective whereas high levels are damaging in an ex-vivo model of ischemic injury, and ALDH2 is a

major, but not the only, regulator of cardiac acetaldehyde levels and protection from ischemia.

A study reported in the November 2018 issue of the Journal of Biology and Medical Research looked at the

clinical evolution of long-term red wine drinkers in relation to coronary artery calcification (CAC). 200 healthy

male habitual red wine drinkers were followed and compared to 154 abstainers for a period of 5.5 years.

During the follow-up, major adverse cardiac events were significantly lower in drinkers than abstainers, despite

higher CAC determined by coronary computed tomography angiography. Greater CAC values in this setting did

not predict a worse prognosis.

Cancer

Research has found links between alcohol and certain cancers including mouth, upper throat, esophageal,

laryngeal, breast bowel and liver. The risk of developing cancer is directly related to the amount of alcohol

imbibed. Smoking along with alcohol produces a significantly greater risk of cancers of the upper airway and

digestive tract.

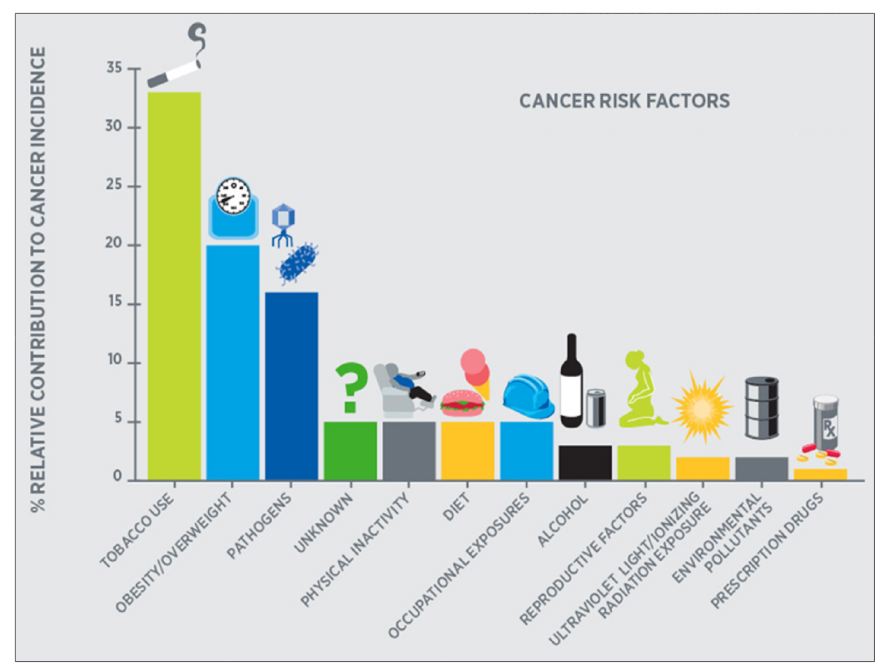

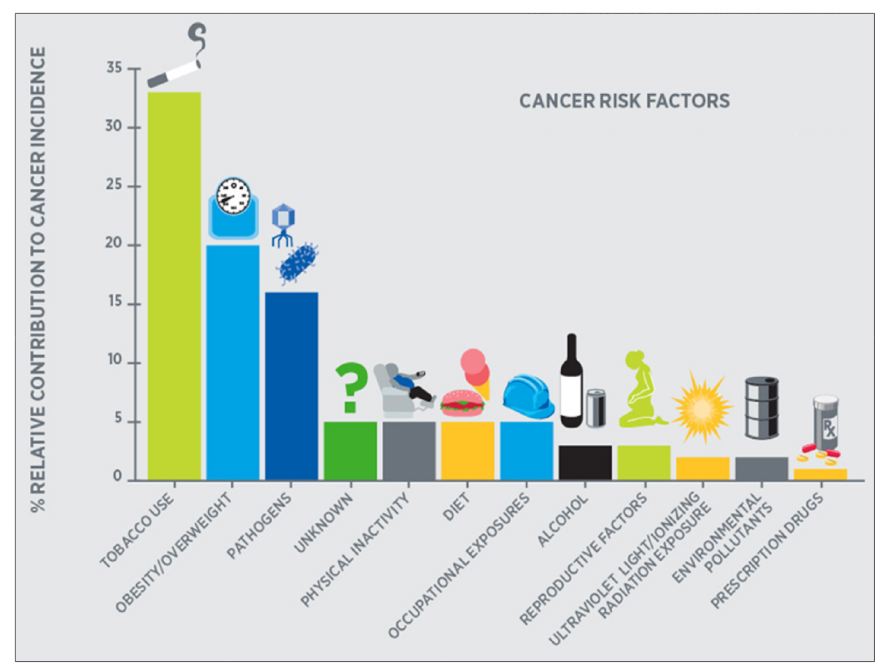

At the International Meeting on Alcohol and Global Health in September 2018, Dr Henk Hendricks of The

Netherlands discussed the contribution of alcohol consumption to the overall incidence of cancer in the

Western world. Among cancer risk factors, alcohol’s contribution is estimated at about 3%. Cancer risk factors

are illustrated in the chart below from that study. Low alcohol consumption (up to 15 g/day) may be associated

with overall cancer incidence and therefore cancer risk. Higher alcohol consumption (<15 g/day) is associated

with an overall increased cancer incidence of 3-8% at 15-30 g/day and 5-19% at 30-50 g/day. Overall cancer

risk may increase in women at a daily consumption that is about half that of men. Cancer risk is only increased

substantially when drinking 60 g (about 4 standard drinks) or more of alcohol per day. Dr. Hendricks’ analysis

suggests that drinking in moderation does not have a substantial impact on overall cancer risk and is

less important as a cancer risk compared to lifestyle factors such as smoking and obesity. Hendricks

stated that light and moderate alcohol consumption is only associated with breast, prostate, ovarian, gastric

and colorectal cancer (there are a number of studies that dispute this association except for breast cancer -

see research reports below).

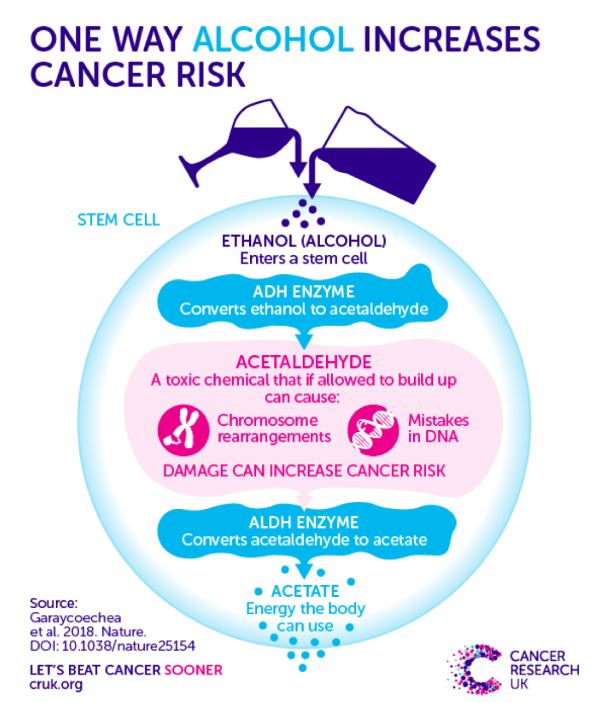

A culprit in the link between alcohol and cancer is likely acetaldehyde, the breakdown product of alcohol

metabolism. University of Cambridge researchers reported in Nature in January 2018 that acetaldehyde can

damage DNA with the blood stem cells of mice causing mutations that might lead to higher risk.

An NIH-AARP large diet and health cohort study published in the International Journal of Cancer in 2018

concluded that alcohol consumption was not associated with the increased risk of gastric cardia

adenocarcinoma and gastric non-cardia adenocarcinoma. The ISFAR critique identified potential confounders

in this analysis, but reviewers considered the results did support the lack of an association between

light-to-moderate alcohol intake and the risk of cancer. The results did not support the fact that wine might

have additional benefits over beer and spirits in terms of cancer risk.

A European meta-analysis of observational studies published in the European Journal of Cancer Prevention in

September 2018 suggested that any wine consumption was not associated with the risk of colorectal

cancer in men and women.

A recent meta-analysis at the University of Vienna reported in Clinical Epidemiology in 2018 pulled together 17

previous studies covering more than 600,000 men. The results suggested that high levels of antioxidants such

as resveratrol in red wine may have a protective effect and reduce the risk of prostate cancer among men by

about 12 percent. Drinking white wine appeared to raise the risk by 26 percent.

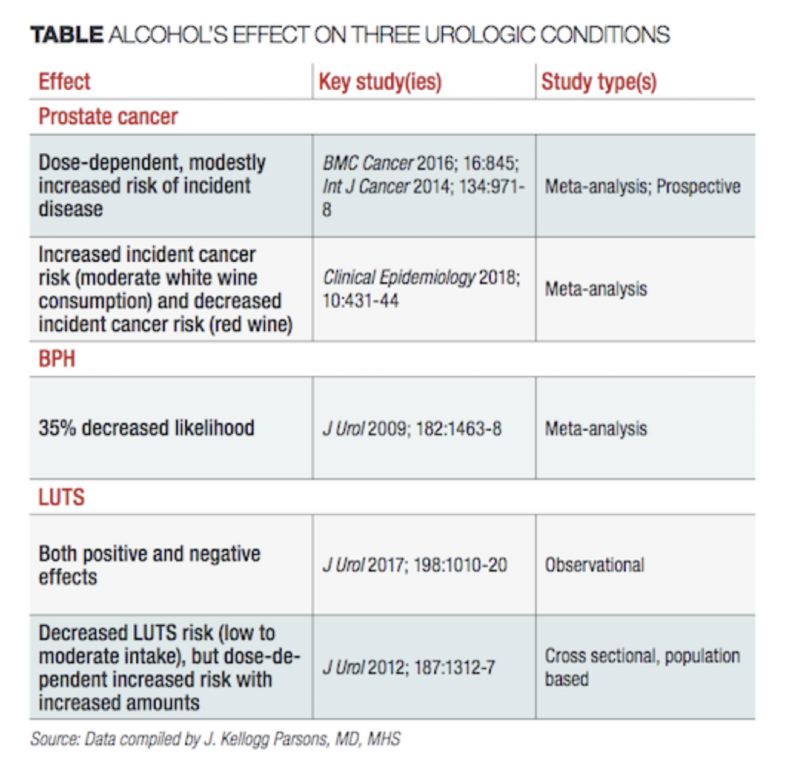

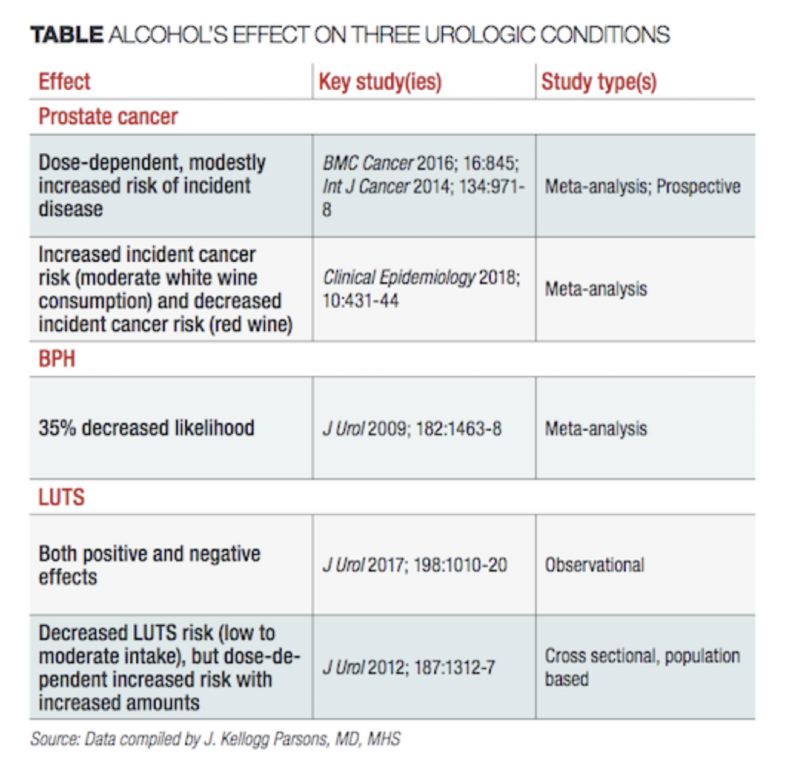

J. Kellogg Parsons MD, writing in Urology Times in September 2018, discussed the effect of moderate alcohol

intake on prostate cancer, benign prostatic hypertrophy (BPH) and lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS). the

table below summarizes alcohol’s effect on three urological conditions. For prostate cancer, studies have

shown alcohol to be neither beneficial or harmful. Some in-vitro and animal studies suggest that the

polyphenol resveratrol has anti-neoplastic activity, but there are no conclusive studies to demonstrate that

resveratrol prevents or protects against prostate cancer.

The International Agency for Research on Cancer estimates that for every drink consumed daily, the risk of

breast cancer goes up 7 percent. More than 100 studies over several decades have reaffirmed the link

between alcohol and breast cancer. It is known that acetaldehyde binds to DNA and this may be responsible

for mutations that can lead to cancer. Also, alcohol increases estrogen levels and this can prompt faster cell

division in the breast leading to mutations and cancer.

ISFAR insights into the relation of alcohol to cancer from studies of alcohol and breast cancer are worth

attention. “The question of alcohol as a cause of cancer has been widely touted by certain investigators and

the lay media. While everyone agrees that large amounts of alcohol contribute to the risk of many cancers,

some scientists continually return to the finding that ‘even light drinking may increase the risk of breast cancer.’

Consuming of as low as 1 drink per day has shown evidence of an increase in the risk of breast cancer in

most studies, although factoring in the intake of folate, binge drinking, concurrent use of hormone replacement

therapy, etc. tend to significantly lower the risk.” It is interesting that a number of large studies

indicate that mortality from breast cancer does not appear to be increased for light-to-moderate drinkers and

may be associated with a reduction in deaths due to CVD as well as overall mortality. The median age for

developing breast cancer is 62 with the highest incidence in women older than 70. Women in this age group

are most susceptible to CVD. ISFAR members agreed that considering overall health and mortality is

necessary when providing advice regarding alcohol consumption; as long as the intake is light, the net

health effects are almost all positive. Women who do not binge drink, have an adequate intake of folate and

are not on hormone-replacement therapy, the risk of breast cancer appears to increase only for consumers of

more than one and a half drinks per day.

There are special concerns for women regarding drinking. Nature has been unfair and has not designed

women for drinking as much as the male. Women weight less than men on average and have more body fat.

Fat has a poor blood supply so alcohol is rapidly distributed to organs where it produces the effects of

drunkenness. They have half as much alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) per unit body mass in the stomach. After

menopause, women begin to develop a distribution of ADH between the liver and stomach that is more similar

to men so they can drink more as a result.

Central Nervous System

University of Rochester research in mice reported in Scientific Reports in February 2018 showed that low

alcohol consumption (about 2.5 drinks per day) reduces inflammation in the brain and helps the brain clear

away toxins, including those associated with Alzheimer’s disease (AD). The clearing process in the brain is the

glymphatic system. This study may explain why previous research has shown that low-to-moderate alcohol

intake is associated with a lower risk of dementia, while heavy drinking for many years leads to an increased

risk of dementia.

A systematic search of 20 systematic reviews published from January 2000 to October 2017 relating alcohol

intake at various time periods to the incidence of cognitive impairment and dementia was pre-published in

January 2019 in Alzheimer’s Research & Therapy. The authors reported that light-to-moderate alcohol use

in middle to late adulthood was associated with a decreased risk of cognitive impairment and

dementia, but heavy alcohol use was associated with changes in brain structures, cognitive

impairments, and an increased risk of all types of dementia. The ISFAR critique considered this a well-done

analysis but recommended further evaluation to understand the reasons and mechanisms that lead to

these associations.

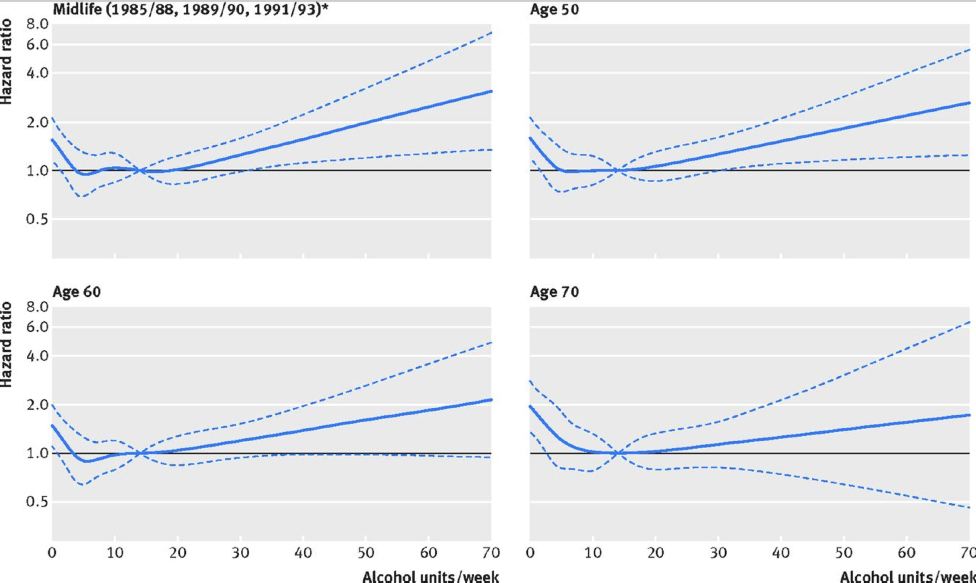

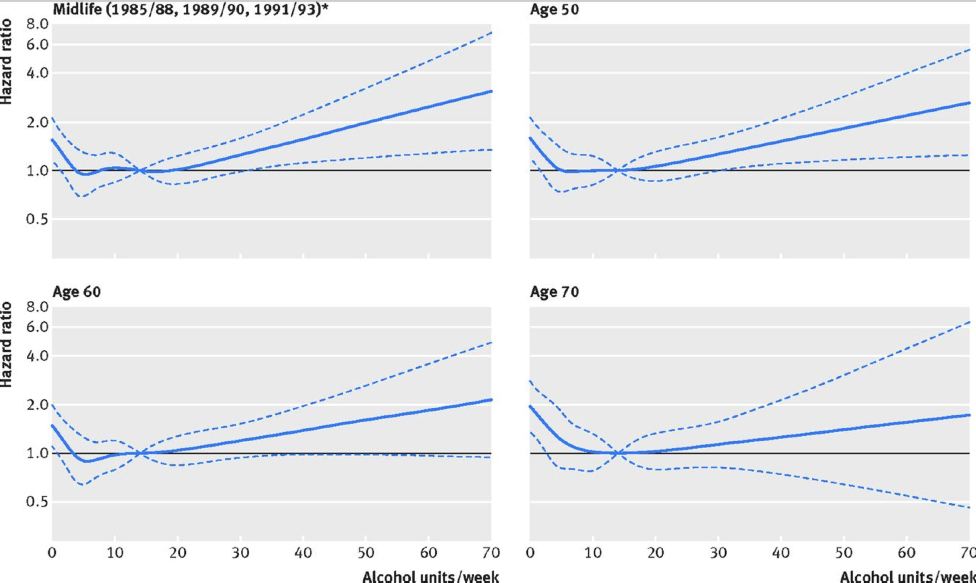

A study of alcohol consumption and the risk of dementia was published in the British Medical Journal in August

2018. The study involved a 23-year follow-up of the Whitehall II cohort study on alcohol and dementia. The

results indicate there is a link between moderate drinking during midlife and a lower chance of developing

dementia later on. The group that abstained from alcohol and the group that drank in excess of 14 units per

week were both shown to be at a higher risk of developing dementia than participants who drank between 1

and 14 units per week. Those in the 1 to 14 units-per-week group tended to drink wine and those who

consumed more than 14 units per week drank more beer. The charts below show the association between

alcohol consumption per week and the risk of dementia by age (dotted lines are 95% confidence intervals). The

data showed that abstainers had a higher prevalence of stroke, coronary artery disease, atrial fibrillation, heart

failure and diabetes mellitus. The ISFAR critique pointed out that this was a well-done study but was based on

self-reporting. The abstainer category was broad and included people that have drunk considerably before the

study began and those who occasionally drank. As an observational study, no direct cause-and-effect link

between drinking and dementia can be inferred. There is no data presented that permits an estimate of the

level of intake where the risk of dementia exceeds that of non-drinkers. Conclusion: in terms of the risk of

dementia as well as CVD, middle-aged and older individuals who are consuming alcohol moderately

and without binge drinking should not be advised to stop drinking.

A review article that appeared in Beverages Journal in 2018 by researcher Paula Silva reported on the

neuroprotective abilities of the wine polyphenols in correlation to the pathophysiological mechanisms involved

in AD. The conclusion was that moderate consumption of wine is one of the main factors behind the

neuroprotective effects observed in some populations, and is due to a combination of neuroprotective effects of

wine phenolic compounds.This paper included a chart of total phenols in mg/L of young white wine - 209.5,

aged white wine - 285.2, young red wine - 1,732, and aged red wine 1,742. The varietals were not specified.

Several case-control studies have suggested that alcohol consumption may be a protective factor for

Parkinson’s Disease (PD). A meta-analysis published in the Journal of Neurology in August 2018 suggested a

protective effect between moderate alcohol consumption and PD, which is supported by the results of case-control

studies but not clearly by prospective ones.

Pregnancy

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports that about one in ten pregnant women in the

U.S. ages 18-44 reports having at least one alcoholic beverage in the past 30 days while pregnant. The

numbers of alcohol use during pregnancy are higher in other countries - between 40% and 80% in the United

Kingdom, Australia and New Zealand. A survey of 1,032 people conducted by Cameron Hughes Wine and

reported in the July 2018 issue of Women’s Health found that 35% of people think it is ok to drink while

pregnant and 65% said you should never drink during pregnancy.

The American Academy of Pediatrics, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and the

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism including the CDC recommend that women avoid drinking

completely if they are pregnant, or if they are not using birth control and there is any chance they might be

pregnant. No amount of alcohol during pregnancy should be considered safe as a safe level has not

been determined. There are studies that suggest light drinking might not be harmful to the baby but women

may have different susceptibilities.

Jen Gunter MD, an OB/GYN physician, wrote in the February 5, 2018 issue of The New York Times, “It is

medically best not to drink alcohol during pregnancy…not even a little…the truth is that fetal alcohol

syndrome is far more common than people think, and we have no ability to say accurately what level of

alcohol consumption is risk-free.”

A Spanish study reported in Alcohol in March 2018 used maternal hair testing to disclose self-misreporting in

drinking and smoking behavior during pregnancy. 35.3% of participants did not drink alcohol at any point during

pregnancy, 62.7% of participants consumed repeated moderate amounts of alcohol during pregnancy, and 2%

consumed repeated consumption of heavy amounts of alcohol during pregnancy. Conclusion: close to two-thirds

of pregnant women in this study drank some amount of alcohol during pregnancy, while only 3%

admitted to drinking alcohol during pregnancy.

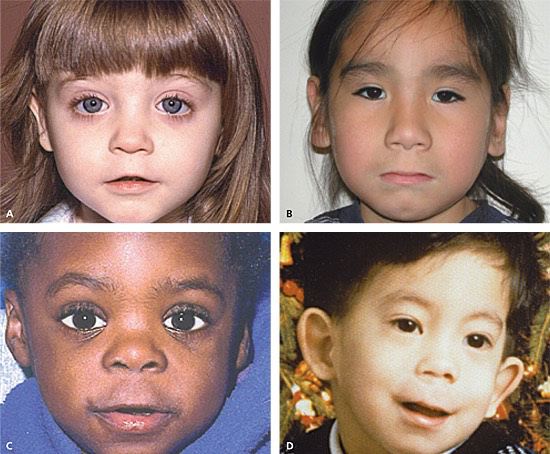

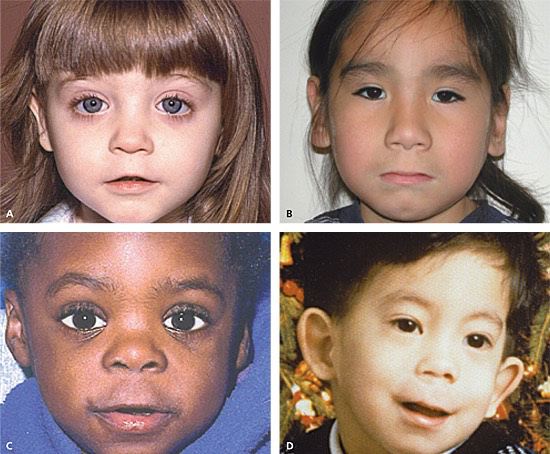

The prevalence of the Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) in four U.S. communities was reported in JAMA

in 2018. FASD is a group of postnatal conditions, first recognized in 1975, that may include abnormal growth

and facial features (see photos below), intellectual disabilities and behavioral problems. Alcohol is known to be

a teratogen that can cause birth defects. This study estimated that up to 1 in 20 kids in the communities studied

fall somewhere on the spectrum of disorders caused by maternal drinking. This was a conservative estimate

but could be as many as 1 in 10 (the commonly accepted estimate is 1 in 100). The disorders can be hard to

recognize so the incidence of the problem is underestimated and are more common than previously thought.

More women are consuming alcohol during pregnancy than previously thought at least in some communities.

The criticism of this study is that the prevalence may have been overestimated and underestimated in different

ways due to how the data was collected. More research is needed.

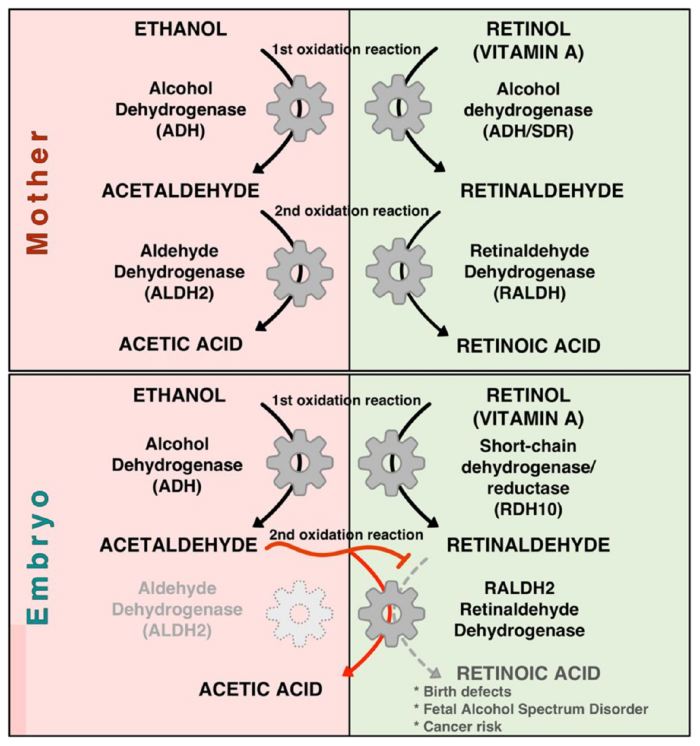

Biochemical and developmental evidence was provided in Scientific Reports in January 2018 showing that

acetaldehyde, the metabolic byproduct of ethanol metabolism, inhibits retinoic acid biosynthesis to mediate

alcohol teratogenicity in embryos. This research provided evidence that acetaldehyde is the teratogenic

derivative of ethanol responsible for developmental malformations characteristic of the FASD. Refer to the

chart below.