The Long and Winding Pinot Road

The Long and Winding Pinot Road is a story that chronicles my almost 50-year love affair with Pinot Noir. I

reflect upon where I started, how far I have come and how I assumed the moniker, “Prince of Pinot.”

I never drank wine growing up. Like most Irish families of the 1950s, beer and cocktails were the drinks of

choice for most adults. Alcoholic beverages were rarely seen on the dinner table, except for maybe an

occasional beer when chili was on the menu. I can’t remember when had my first drink of dry wine, but I think

it was a French Champagne brought to my house by my French aunt.

The quartet of wines I remember most fondly had a little sweetness. Mateus was a moderately dry Rosé wine

from Portugal. The story goes that the wine was invented in 1942 by Fernando Van Zeller Guedes whose

family made Port and grew Vinho Verde grapes. Mateus was the “in” drink in the 1960s and at one point the

wine made up 40% of Portugal’s export income. Practically every college-age person had an empty Mateus

flask that was converted into a candle holder.

I also downed many bottles of another similar drink called Lancers which had become wildly popular by 1970.

André Cold Duck was still another star during the 1960s, a slightly sweet sparkling wine made by Gallo from

Concord grapes that were guaranteed to provide an agonizing hangover the next day. Blue Nun was the wine to

order on a date. It was packaged in an impressively slim and tall bottle and had a label that read Liebfraumilch

(“Milk of Our Blessed Mother”). This generic white wine was also slightly sweet, but even better, it was cheap

and low in alcohol.

As I progressed through the end of high school, then college at Stanford University, and then UCLA Medical

School during the 1960s, I was to occupied to be interested in wine. In 1970, however, my world would become transformed.

1970 was a great year for me. I was living humbly in a studio apartment close to Harbor Hospital in Torrance,

California, where I was interning. My girlfriend was a flight attendant (they were called stewardesses back then)

for TWA. I was working my tail off, but when our busy schedules allowed, I would pick her up at Los Angeles

International Airport after a long flight. We would stop at a market and buy some food as well as a jug of

Spañada. Spañada was one of a long line of wines blended with fruit and introduced by Gallo. It was the

original Spanish-sounding wine. Spañada was first marketed in 1970 at a time the country was changing its

taste from dessert to table wines.

My girlfriend was my first love who I had met at Stanford. We spent many marvelous evenings together at a

tiny two-seat kitchen table in my small apartment, eating simply and drinking Spañada. The Spañada inevitably

led to romance and I thanked Gallo many times for that.

That same year, I traveled to Northern California to visit some friends, including a doctor who collected wine.

He had a cellar in his home stocked with fine Bordeaux and Burgundy and I had never seen anything like it. He

could tell I was awestruck and generously gave me a bottle of Premier Cru red Burgundy to take home.

One night my girlfriend and I decided to skip the Spañada and open the Burgundy. I did not have a corkscrew

and had to borrow one from a neighbor. Needless to say, it was like no wine that had ever passed across my

lips. The label was strange and foreign, and although I remember the words Côte de Nuits on the label, I forgot

the vintage and name of the producer. The wine was seductive, beguiling, alluring, complex and aromatic. It

was truly an epiphany.

We polished off the bottle in no time and so began my love affair with Pinot Noir. I kept the empty bottle on my

kitchen table until I moved out after my internship. I was beginning a residency at Jules Stein Eye Institute at

UCLA that offered an increase in salary and the prospects for further wine indulgences were dancing through

my head. My girlfriend and I parted ways, but I discovered the wonders of well-stocked liquor stores and began

to look for that elusive Burgundy experience.

While looking for red Burgundy wines in my price range, I found slim pickings, and the ones I could afford were

thin, rustic, acidic and terribly disappointing. The alternative, California Pinot Noir, was not worth pursuing in the

early 1970s. There were some signs of success coming out of Mt. Eden and Chalone, but these were off my

radar and might as well have been on another planet. Frustrated, I turned to the dark side and began to dabble

in Cabernet Sauvignon, Zinfandel and Petite Sirah. I was particularly drawn to Petite Sirah because of its bold

blackberry jam flavors and black pepper spice. It seemed to be a perfect accompaniment to my culinary

achievements that consisted primarily of grilling steaks on the barbecue.

There was one Petite Sirah producer in particular that caught my attention - Concannon Vineyard. Maybe it

was the fact that Concannon was the first California winery to label the varietal Petite Sirah on the bottle (in

1964), or maybe it was because the winery had some familiar kinship (founder James Concannon was born on

St. Patrick’s Day in Ireland, the homeland of my great grandfather). Most likely, though, it was because I like

the masculine nature of the wine, and as a young bachelor, I identified with its machismo style. Concannon

Vineyard, located on the East Bay of Northern California in Livermore, was the first winery I visited. It was

around 1974 when I went to Concannon and bought a case of wine, one of life’s rites of passage.

I began my solo practice of ophthalmology in Orange County, California, in 1975. My marriage followed in

1977, and two sons came into this world shortly thereafter taking my attention away from wine for a few years.

Mr Stox Restaurant in Anaheim, California would eventually revive my passion.

In 1977, brothers Ron and Chick Marshall purchased an existing restaurant named Mr Stox and converted it

into a destination dining mecca for foodies and wine lovers. The restaurant quickly amassed an impressive

collection of wine and by 1983 had earned a Wine Spectator Grand Award, an award they retained for many

years.

Comfortably married and established in medical practice in the early 1980s, and benefiting from some

spendable income, I began to take a renewed interest in wine. I attended many winemaker dinners at Mr Stox,

the most memorable of which featured the wines of Domaine Romanée-Conti (DRC).

I had gained an interest in Chalone Pinot Noir. Chalone, founded in 1969, had developed a cult following in the

latter 1970s and the wines were quickly snapped up by wine fanciers of the time. Owner and winemaker

Richard Graff had purchased and farned the Chalone property located on a wind-swept plateau in the Gavilan

Mountains, a remote outpost 50 miles east of Monterey. Graff chose the site because of its volcanic soils

underlain with limestone.

Graff’s winemaking was modeled after that practiced in Burgundy and his Pinot Noirs reminded me of the DRC wines I had

tasted at Mr Stox. The Chalone Pinot Noirs were fermented with stems (whole cluster) that gave them

structure and longevity. Graff was one of the first people in California to buy French oak barrels and he aged

his Pinot Noir 18 to 21 months in the same French oak barrels being used at the time at DRC. The barrels were

kept in caves that were cool and dark and later, put into special bottles made in France from a special

Burgundy mold.

I was particularly fond of the Chalone Reserve Pinot Noirs first produced in 1978. The winery skipped a year,

then began a regular reserve program in 1980. They were focused, tightly-knit and well-balanced with many

layers that revealed themselves slowly with each sip. The Reserve Pinot Noirs were produced only from old

vines on the property and sold directly only to members of the Chalone mailing list (priced at $18 to $26). I

became a Chalone shareholder in order to acquire the wines and annually attended the shareholders

bacchanal held at the Chalone property.

My burgeoning interest in Pinot Noir coincided in the mid-1980s with the emergence of California and Oregon

Pinot Noir as wineries began to figure out that Pinot Noir loved cooler climates, welcomed gentle handling and

needed kid-glove handling in the winemaking process.

My love affair with Pinot Noir was fully engaged by the late 1980s and I was looking for a new source I could

hitch my grape wagon to. In 1989, noted wine writer Dan Berger wrote a glowing report in the Los Angeles

Times, calling Gary Farrell a “Pinot Noir Superstar.” In the article, he listed the best Russian River Valley Pinot

Noir producers at the time as Joseph Swan, J. Rochioli, Davis Bynum, Williams Selyem, Laurier, Dehlinger,

Mark West, Iron Horse and De Loach. Among this distinguished group, Berger named Farrell as the best and

noted that Farrell’s 1988 Sonoma County Pinot Noir ($15) was superb, but the 1988 Allen Vineyard Pinot Noir

($25) was “a killer and one of those rare treats worth the price.” In this article, Farrell said, “There are probably

fewer than 500 acres of top-quality Pinot Noir vineyard land here. The Russian River Valley hasn’t gotten the

publicity of some other areas, but that’s ok. Actually, we’re trying to keep this thing quiet because of the limited

acreage out there.”

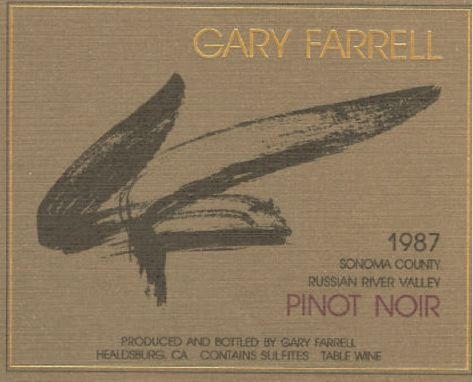

I had sniffed out Gary Farrell even before the glowing article written by Dan Berger, having already made my

first purchases of 1987 Gary Farrell Russian River Valley Pinot Noir ($20, see label below). The wine made

such an indelible impression on me that I still have the label to this day.

The wine was produced from Howard Allen Vineyard (40%), Bacigalupi Vineyard (40%) and Rochioli Vineyard

(20%), all located within a few miles of downtown Healdsburg. The grapes were hand-harvested, gently destemmed

taking caution not to break the skins on about 50% of the berries. The grapes were fermented in

small two-ton lots using Assmanhausen yeast for eight days and inoculated with MCS ML bacteria at 12º Brix.

Pressing occurred at dryness and the wine was allowed to settle for four weeks before barreling. The wine was

then aged 14 months in French oak barrels, 30% new.

I became a steady customer of Gary Farrell Pinot Noir while as the wines accumulated numerous accolades

and competition medals over the years. I was thoroughly charmed by the wines’ enticing aromas, lush and

broad fruit flavors, modest tannins, bright natural acidity and sweet oak highlights. Farrell was notoriously shy,

but I did get to meet him after he had left Gary Farrell Vineyards & Winery in 2006 and started Alysian Wines. I

tasted with him over his marvelous 2008 Alysian Pinot Noir and Chardonnay wines and found him to be very

soft-spoken, calm and polite, with an attractive smile and golf tan that belied his age. It has been my

observation that a winemaker’s wines often reflect the winemaker’s personality and I think that was reflected in

both the Gary Farrell and Alysian wines.

My loyalty to Gary Farrell wines did not waver, but there was another Russian River Valley Pinot Noir producer

who stole my heart away in the early 1990s. At this time, liking Pinot Noir practically labeled me an eccentric.

To most wine lovers of that time, Pinot Noir was an afterthought and considered a weak substitute for Cabernet Sauvignon or Merlot. For me, Pinot Noir was the Holy Grail, the most sensual of all wines, and I was bound

and determined to pursue my love affair in earnest.

Burt Williams and Ed Selyem were able to produce magical Pinot Noirs out of a small garage on Fulton Road

in Santa Rosa beginning in the early 1980s. There had been significant press since 1985 touting the quality of

the Pinot Noirs from notable vineyards like Rochioli, Allen, Hirsch and Olivet Lane. It was a 1992 Williams

Selyem Rochioli Vineyard Pinot Noir that made such a powerful impression on me that even today I can taste

the wine, and still believe it to be the greatest California Pinot Noir I have ever had in my life. I joined the

mailing list in 1990 and eagerly purchased my yearly allocation of Williams Selyem Pinot Noirs.

I reached my 50th birthday in 1993 and decided to have a celebratory degustation dinner at The Pacific Club

in Newport Beach, California. My friend and sommelier extraordinaire, Rene Chazottes, planned the food to

accompany my wine selections. Rene was the one person who made me fully understand that wine, alone

above all beverages, was part of food, and neither existed in even half its glory without the other. As Rene used

to say, “Wine is made for drinking with food and when you have the perfect match, that is it, the experience will

bring you to your knees!” I still wax nostalgically about the wines served that night to my group of friends: 1990

Domaine Ramonet Bourgogne Algoté with Créme de Cassis (Kir), 1989 Zind Humbrecht Riesling Brand Grand

Cru Vendage Tardive, 1989 Williams Selyem Rochioli Vineyard Russian River Valley Pinot Noir (magnum),

1985 Comtes Lafon Les Caillerets 1er Cru Volnay, 1982 Chalone Reserve Pinot Noir, 1943 Cheval Blanc (my

birth year wine), 1982 Cheval Blanc, 1984 Silver Oak Bonny’s Vineyard Cabernet Sauvignon (magnum), 1990

Williams Selyem Martinelli Vineyard Zinfandel, 1989 Gaston Huet “Cuvée Constance” Vouvray, and 1982

Laurent Perrier Cuvée Alexandra Rosé Champagne. It was the last big dinner I planned where I drank varietals

other than Pinot Noir and was clearly a night of ridiculous overindulgence.

I joined a monthly gathering of twenty wine enthusiasts in January 1989 that cleverly called themselves “Le

Grand Crew.” The group met for wine tasting and dinner most often at Mr Stox Restaurant in Anaheim,

California. The guidelines for membership dictated the following: “Members must have a serious interest in

wine, have their own wine collection, and have a desire to enhance their palate and wine education through

group tastings.” The overriding premise was that this would not be a pompous group of wine snobs and good

jokes would be encouraged at all tastings. Le Gand Crew was a major source of my wine education and

inspiration, and with but few member changes, persisted well over twenty years. We typically met monthly over

a gourmet 4-course dinner, traveled to wine regions together, and we (women were not specifically banned but

few dared to attend) developed friendships for life.

Through many Le Grand Crew dinners over the ensuing years at Mr Stox, I became exposed to all of the great

wines of the world, but I was still hopelessly hooked on Pinot Noir. This led to the series of “Super Bowls of

Pinot Noir.”

Early on, I was an outcast and weirdo, the butt of jokes for my professed love of Pinot Noir. The members were

dedicated domestic Cabernet Sauvignon and French Bordeaux drinkers with little interest or patience for other

varietals. That was all to change, when in 1991, I organized my first “Superbowl of Pinot Noir” dinner tasting for

Le Grand Crew. The idea was to present the champions, the best of the best New World Pinot Noirs that were

available in the marketplace at the time. Over the years, the Le Grand Crew members looked forward to the

“Superbowl,” and many eventually abandoned the dark side for Pinot Noir.

The wines tasted at “Superbowl 1 of Pinot Noir” were the following: 1987 Au Bon Climat Sanford & Benedict

Vineyard Santa Ynez Valley Pinot Noir ($30), 1987 Calera Jensen Vineyard Mt. Harlan Pinot Noir ($30), 1987

El Molino Napa Valley Pinot Noir ($30), 1987 Williams Selyem Rochioli Vineyard Russian River Valley Pinot

Noir ($40), 1988 Gary Farrell Allen Vineyard Russian River Valley Pinot Noir ($25), 1988 Robert Mondavi

Reserve Napa Valley Pinot Noir ($29), 1988 Signorello Proprietor’s Reserve Napa Valley Pinot Noir ($25), 1988

Williams Selyem Sonoma Coast Pinot Noir (425), 1989 Byron Santa Barbara County Pinot Noir ($18), 1989

Etude Napa Valley Carneros Pinot Noir ($22), and 1989 Williams Selyem Olive Lane Vineyard Russian River

Valley Pinot Noir ($25). Looking back, this was a heck of a lineup and a glimpse of California Pinot Noir history.

In 1993, I was hosting “Super Bowl of Pinot Noir II.” It was a time when the wine cognoscenti were becoming

awakened to American Pinot Noir as producers began to wave the flag proudly, sticking out their chests, and

proclaiming how good home-grown Pinot Noir had become. The event that catapulted Pinot Noir into popularity

happened in the early 1990s and involved a ten-letter word. Several of California’s most notable Pinot Noir

winemakers became winegrowers. This one word led to a revolution in philosophy and practice, and the results

led to a quantum leap in quality over previous efforts of a few years prior. The most talented winemakers in American realized their success lay not in the winery but in the vineyard. American winemakers were energized

and now wanted to craft it and the most enlightened drinkers wanted to consume it.

“Superbowl II of Pinot Noir,” also titled “Second Encounter of the Pinot Kind,” offered the best of the 1991

vintage and included Oregon Pinot Noir for the first time. The lineup was memorable: 1991 Domaine Drouhin

Oregon Willamette Valley Pinot Noir (first vintage), 1991 Ponzi Reserve Willamette Valley Pinot Noir, 1992

Beaux Frères Willamette Valley Pinot Noir (first vintage), 1991 Saintsbury Reserve Carneros Pinot Noir, 1991

Schug Heritage Reserve Carneros Pinot Noir, 1991 El Molino Napa Valley Pinot Noir, 1991 Rochioli Estate

Russian River Valley Pinot Noir, 1991 Williams Selyem Allen Vineyard Russian River Valley Pinot Noir and

1991 Sanford Sanford & Benedict Vineyard Santa Barbara County Pinot Noir.

My wine drinking buddies of Le Grand Crew, most of whom had been raised on California Cabernet Sauvignon,

were surprised by the full, deep, rich scents and flavors of the Pinot Noirs. They found Pinot Noir very hard to

say no to, seduced by its sensual and indulgent nature that melded delicacy and intensity like no other grape

varietal they had experienced. A number of these die-hard Cabernet Sauvignon drinkers developed an interest

in Pinot Noir and began drinking Pinot Noir regularly while cases of Bordeaux languished in their cellars. They

would remark, “Rusty, you’re such a ‘prince’ for introducing me to Pinot Noir. The moniker stuck, and my nom

de plume became “Prince of Pinot.”

I was soon tasting and drinking Pinot Noir daily, reading about Pinot Noir constantly through all of the available

sources on wine visited pinotcentric wine regions in California and Oregon regularly. I participated as a judge in

Pinot Noir wine competitions and corresponded on Pinot Noir for a popular wine podcast on the internet called

Grape Radio. I appeared in a video produced at Grape Radio on the Russian River Valley that won a James

Beard Award.

American Pinot Noir was proving its worth and my passion for it had been vindicated. However, it was time to

visit the cradle of Pinot Noir, the slopes of the Côte d’Or. Master Sommelier Rene Chazottes led a small group

of wine enthusiasts on a wine and gastronomic tour of France in June 2000. Our group’s battle cry was “Mon

verre est vide!” (my glass is empty). 1 bus, 2 drivers, 4 hotels, 18 wineries, 22 cities, 24 meals, 185 wines, and

370 bottles of wine on a trip that included Champagne, Burgundy, Loire Valley and Bordeaux. For me, the

highlight of the trip was the heartwarming sight of the almost unbroken vista of vines carpeting the slope of the

Côte d’Or on a gloriously sunny day. As we drove leisurely along RN 74, the most evocative signs to villages

appeared, the names of which sounded like a roll call of the most seductive red wines in the world: Chambolle-

Musigny, Vougeot, Vosne-Romanée and Nuits St. George.

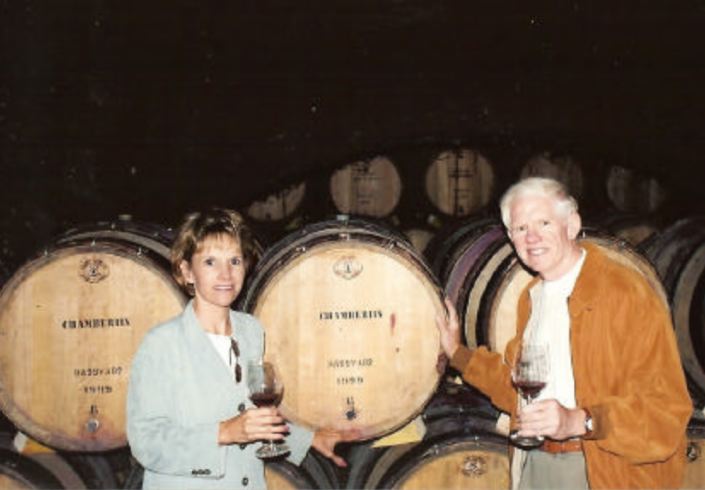

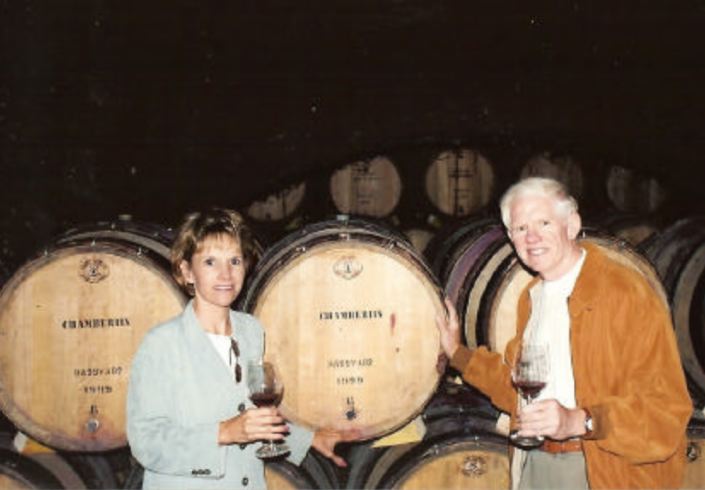

At Louis Latour in Aloxe-Corton, I drooled over the library of Burgundies dating to the 1800s, including bottles

with no labels and covered in mold. The winemaker’s thief was put into action and I tasted some terrific 1999

vintage wines including Corton Charlemagne and Chambertain (photo below is of my wife Patti and I in the

cellar at Louis Latour with a sample of Chambertain in hand). Needless to say, I did not spit these wines out.

Later that day, we continued south along the Côte de Beaune to the lovely, old and very rich town of Beaune. I

marveled at the perilously narrow streets, medieval houses, grandiose mansions and a Romanesque church.

Our group settled in at the Renaissance mansion hotel, La Cep, close to the action in central Beaune. Then it

was off to Vougeot for a tasting and dinner at Domaine Bertagna. With only 200 inhabitants and 67 hectares of

vines, Vougeot is the smallest commune in the Côte d’Or. A spectacular dinner ensued at Domaine Bertagna

that included the following wines: 1995 Domaine Bertagna Corton Charlemagne, 1995 Domaine Bertagna Clos

St Denis (magnum) and 1995 Domaine Bertagna Vougeot Clos de la Perriere Monopole 1er Cru. We drank

and sang the “Ban de Bourgogne.” While I was far away, I felt at home in Burgundy.

I awoke after our previous night’s revelry at Domaine Bertagna and decided to walk off the lovely Pinot

hangover. I started to think that I had died and gone to heaven. One in our group would remark, “Give me a

break, it’s only a bottle of wine.” Right, and a Ferrari is only a car and the Rolling Stones are just a rock band.

Some things in this world become the standard against which all else is measured and I realized for Pinot Noir,

the standard was Burgundy. Although California Pinot Noir compares favorably with Burgundian wines in a

number of instances, many California examples were to Burgundy what the World Wrestling Federation was to

athletics. This is not to say that we should spend needless energy comparing North American Pinot Noir to

Burgundy. They both should be enjoyed for the qualities that they offer and to suggest they are comparable is a

disservice to both.

A visit to Burgundy is magical. The simplicity of each Domaine’s houses and the purity of the line of the stone

enclosures surrounding the vineyards cling to my memory. The history, tradition and intimacy of the beautiful

farm-based countryside make the wines seem even more magical. Some people call Burgundy “liquid silk,” and

others would say it as close as you can get to a romantic interlude with your clothes on. In either case, fine

Burgundy is a kaleidoscope of heady aromas and flavors that will spin your head around, set your pulse racing,

and leave you totally at peace with the world.

Every dedicated pinotphile seems to have begun their journey of discovery after tasting a remarkable

Burgundy. I am no exception and my travel to the “motherland” only cemented my epiphany in my memory.

As I flew home from Paris, I was reminded of what Louis Trebuchet said after our group polished off 34 bottles

of fine white Burgundy at a luncheon at Domaine Chartron et Trebuchet in Puligny-Montrachet: “Bordeaux

makes women say things they shouldn’t say, but Burgundy makes women do things they shouldn’t do.” I

glanced over at my wife longingly, eager to return to home in California.

The inspiration and derivation of the name of my online wine newsletter, the PinotFile, came about because of

my pent-up urge to share my passion for Pinot Noir with others. I felt like an evangelist who needed to spread

the gospel and decided to focus on domestic Pinot Noir. I sat down on a Sunday night, April 22, 2001, to be

exact, and began to type a one-page missive on Pinot Noir that I intended to send out by email to the twenty

members of Le Grand Crew and a few other friends. I alerted my inaugural readers as follows: “Every Sunday

night I am going to email a short newsletter titled the PinotFile to keep you apprised of news in the pinophile

world. If you could care less, too bad, you have been pinot-spammed.” The communication included

recommendations of what to buy, what not to buy, winemaker profiles, winery news and wine ratings. I did not

believe in giving wines numerical scores but did initially report the scores of other wine critics. I soon discarded

this practice by 2008 when I began to accompany my reviews with scores based on the 100-point system.

From the beginning, humor has played a large role in the PinotFile. The inaugural issue featured a tongue-in-cheek

wine review that was proffered from the now defunct Wine X magazine. “1999 Cannotpronounce Cellars

Pinot Noir. Special Family Reserve, Olive Grove Vineyard, Southwest Facing Slope, Behind the Barn, Vertical

Corton Trellised, Fifth Row, Third Vine from the Right, North Cane, First Bunch from the Left, Unfined,

Unfiltered, Barrel Aged, Barrel Fermented, Estate Grown, Estate Bottled, Estate for Sale. Winery founded in

1981 by a fifth-generation billionaire. $110.99.” The review went on to say, “I don’t know why I should bother

trying to explain such a great wine to mere mortals such as you. It’s like explaining rain to people who don’t

know what water is. But, I will make an attempt. At first whiff, there is an attack of acid-hydrolysates, vindaloo

paste and ciruela. The aromas are very feminine and may make some question their sexuality. The wine

explodes in the mouth, saturating the palate and I am certain this is a masculine wine in drag. But it is good

and a wine to remember. 1,000 cases produced, but not for sale because it is the family’s private reserve!”

I finished the single page, hit the send box and the PinotFile was off and running.

The first 53 issues of the PinotFile were emailed in a one to two-page format (see photo below). By June

2002, the PinotFile took on a four-page format. As the years and weekly issues rolled by, I infused the

PinotFile with a purpose. I chose to circumvent the many wine publications of the time that centered primarily

around lengthy lists of tasting notes and scores. My intent was to find and report the compelling stories behind

every good bottle of Pinot Noir. Because of the serious commitment in time, effort and money that Pinot Noir

producers put into the bottle, I avoided derogatory reviews of Pinot Noirs that were not appealing to me. I

strove to give a truthful judgment and only feature and recommend Pinot Noirs that I deemed worthy of reader

interest. I initially avoided scoring wines and instead preferred to give some helpful comments that revealed the

style and spirit of a wine that would lead readers on a path of discovery. That said, I always emphasized that

every wine drinker possessed a different palate, so the recommended wines were meant to be only a starting

point for the reader’s own exploration of Pinot Noir.

I began to receive a continuous stream of testimonials from grateful readers who seemed happy with my

unpretentious and humorous approach to reviewing wine, and I am truly appreciative of each and every one. I

particularly enjoyed one bit of feedback from a reader: “If I drank over 1,300 wines during the year, my wife

would accuse me of having a drinking problem. You do it, call it research, brag about it, and gain respect

among your friends. Way to go!”

The PinotFile became a joyous pursuit, a lengthy cold soak that coincided with the rise in popularity of Pinot

Noir post ‘Sideways” in 2004. I developed an enthusiastic reader base of 50,000 visitors to the Prince of Pinot

website each month. But by 2008, it was time to pull the cork on a new venture.

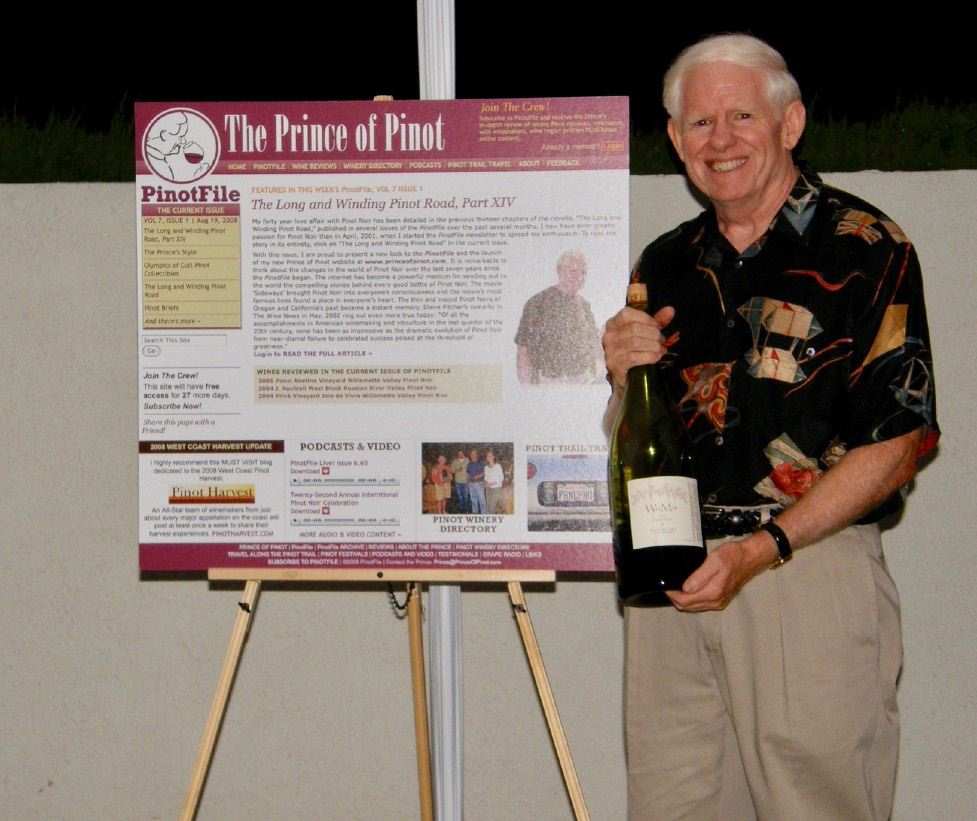

With Volume 7, Issue 1, I debuted a new look to the PinotFile and launched the Prince of Pinot website at

www.princeofpinot.com. I was amazed to think of how quickly changes had occurred in the world of Pinot

Noir over the seven years since the PinotFile began. The internet had become a powerful medium for sending

to the world the compelling stories behind every good bottle of Pinot Noir. The movie ‘Sideways’ had brought

Pinot Noir into everyone’s consciousness and the movie’s most famous lines found a place in everyone’s heart.

The thin and insipid Pinot Noirs of California’s and Oregon’s past had become a distant memory. Steve

Pitcher’s remarks in The Wine News in May 2002, ring out even more true today. “Of all the accomplishments

in American winemaking and viticulture in the last quarter of the 20th century, none has been as impressive as

the dramatic evolution of Pinot Noir from near-dismal failure to celebrated success poised at the threshold of

greatness.”

The PinotFile’s mission statement was by now well elucidated: “To keep readers apprised of news in the

pinotphile world, including latest releases, winery news, winemaker profiles, what to buy, and how to get your

hands on it.” But the PinotFile offered much more. It was packed with first-hand colorful interviews of domestic

Pinot Noir winegrowers and winemakers included periodic appellation and regional profiles of pinocentric wine

regions including photos and maps and offered extensive tasting notes that included winery verticals, regional

horizontals, barrel samples, and older vintages. On the ground reports from wineries were included as well as

reports from the many Pinot Noir festivals and celebrations in California and Oregon.

My tasting notes have always featured a stylistic and unpretentious impression of wines. My byline had been, "No scores, just great noirs." With Volume 7, Issue

2, I began to include wine ratings using the 100-point scoring system. Wineries, retailers and consumers were

demanding it. I had misgivings as did other noted wine critics such as Steve Tanzer and Allen Meadows, but it

became necessary to retain my audience. The Pinot Geek image was introduced, a mythical character of some

repute that designated the Pinot Noirs that received a score of 94 or better. Previously, many readers were

able to read between the lines to discover those Pinot Noirs that really turned me on. It became obvious when

the Pinot Geek appeared in tasting notes signifying wines that were truly exceptional and worthy of attention.

As the French would say, C’est top! (It’s the best).

In May 2010, I came out of the closet, admitted to another paramour and began reviewing domestic

Chardonnay. In Volume 8, Issue 15, the “Golden Geek” and “Golden Value” icons appeared for the first time,

and like their Pinot Noir counterparts, represented the best in Chardonnay (Golden Geek Icon) and the best

values in Chardonnay (Golden Value Icon).

I found that many Pinot Noir producers also craft Chardonnay as the two varietals are natural partners.

Chardonnay is not a true member of the Pinot family of Pinot Noir, Pinot Gris and Pinot Blanc, but as shown by

researchers at UC Davis in 1999, Chardonnay is most likely derived from a fling in the distant past between

Gouvais Blanc and Pinot Noir. Once Pinot Noir producers found out I enjoy and drink Chardonnay regularly

(my wife’s wine of choice) they sent samples for review. That is not to say that the PinotFile took on a “bi”

proclivity. The overwhelming emphasis forever remained on Pinot Noir.

Although my travels sent me repeatedly to many wine regions of California, on many occasions I also journeyed along the Pinot road in Oregon where I developed a kinship with many Oregon producers of Pinot Noir. It was the International Pinot Noir Celebration (IPNC) that really hooked me on Oregon Pinot Noir. The first IPNC was held in 1987 when a group of Oregon winegrowers and winemakers gathered to figure out a way to promote Oregon wine. The even started out modestly and when I first took part around 1990, there were less than 200 attendees. By 2005, the IPNC had moved to the campus of Linfield College in McMinnville and attendance had swelled to 700 cognoscenti from all over the world brought together for three days to revel in their love for the "go-go juice" known as Pinot Noir.

The years that followed the modern era of the PinotFile were filled with memorable Pinot Noir-related trips and

events. There were many reports published from the front lines at the World of Pinot Noir, the Anderson Valley

Pinot Noir Festival, Pinot Days, the West of West Festival, the Pinot Noir Summit and the International Pinot

Noir Celebration. In 2008, there was an extended trip to the Pinot Noir regions of Victoria, Australia, and

Martinborough and Central Otago, New Zealand. In 2001, I was involved in the planning and attended the Burt

Williams Tribute Dinner held at Dry Creek Kitchen in Healdsburg. In 2014, I was invited to Ted Lemon

Celebrates 20 Years of Littorai Retrospective Tasting. In 2015 I flew to Portland to attend A Celebration of the

50th Anniversary of Papa Pinot’s (David Lett’s) Legacy. In 2016, I was part of a panel presenting Return to

Paris: the Bacigalupi Family Celebrates the 40th Anniversary of the Judgment of Paris. In 2018, I attended the

Benovia Winery Cohn Estate Vineyard 45th Anniversary.

Along the way I also tried to solve the mystery of the origins of Oregon’s “Coury clone” and the “828” clone,

who planted Pinot Noir first in the Willamette Valley (David Lett), the history and importation of the Dijon clones

of Pinot Noir, and more recently, the etiology of Grapevine Red Blotch plague. I searched out and reported on

doctors who had become Pinot Noir winery owners, winegrowers and winemakers in Oregon and California. I

did the same for former commercial airline pilots. I confronted controversial subjects such as “minerality,”

alcohol levels (“devil’s spit”), whole cluster fermentation, and the 100-point scoring system. I visited practically

every heritage Pinot Noir vineyard in California and Oregon.

I have weathered boxed and bagged Pinot Noir, canned Pinot Noir, reduced alcohol Pinot Noir, Pinot Noir

Blanc, Trader Joe’s Pinot Noir, Meiomi Pinot Noir, the onslaught of mediocre Napa Valley winery-produced

Pinot Noir and god forbid, I hope to endure the imminent possibility of zero alcohol Pinot Noir. I have seen the

emergence of screwcap closure and glass closure for Pinot Noir, both of which have stalled in popularity in

part due to the reduction in frequency (but not elimination) of cork taint. I have most recently confronted the

Sober-Curious Movement.

When I began publishing the PinotFile in 2001, there were a total of 23,046 acres of Pinot Noir planted in

California. Today, California is the leading domestic producer of Pinot Noir, with approximately 43,000 acres

planted. In 2001, there were 4,834 acres of Pinot Noir planted in Oregon. Today, Pinot Noir is by far the most

planted variety in Oregon, with about 19,700 acres of vines. Pinot Noir accounts for 60% of Oregon’s total wine

production.

A number of people have asked my why I don’t produce Pinot Noir and maybe I am crazy not to. Believe it or

not, people really get paid to make Pinot Noir. I know you thought they did it for free. Who wouldn’t? Ask any

winemaker what he does, and he proudly exclaims he is “hands-off” in the winery (also known as noninterventional

winemaking). A degree in enology is required to do nothing? Winemakers tell me, “I stay out of

the way and let the grapes make the wine.” Winemaking must be the best job in the world.

Winemakers only “work” two months out of the year during harvest. But even then, they hire skilled laborers to

pick the grapes, recruit volunteers to sort the grapes and hire cellar rats to do all the cleaning and dirty work.

They don’t need a wardrobe of nice clothes. As rock music plays in the background, they walk around the

winery ordering cellar hands to do punch downs and selecting the lab tests that a hired enologist performs.

Mainly they just smile and nod their heads, offering encouragement.

The most adventurous winemakers will take on Pinot Noir, but Pinot Noir is the only grape that is wise to the

winemaker’s shtick and likes to mess with their head. Pinot Noir is a chameleon that offers different aromas

and flavors that vary from day to day, sulking at times, and teasingly strutting remarkable sensuality at other

times, but always forcing the winemaker to sweat a bit. Every little thing that is done in the winery can affect the

delicate aromas and flavors of Pinot Noir, so winemakers have learned to do nothing. Respected Pinot Noir

winemakers don’t add yeasts, don’t pump, don’t add coloring agents or flavor concentrates, or acid, don’t fine

and don’t filter. If they don’t do much, what exactly do they get paid for? Winemakers are trained masters of

smiling and nodding. Maybe I missed my calling.

The legacy of the PinotFile and the Prince of Pinot website:

1 The first wine newsletter exclusively devoted to one variety - Pinot Noir, and one group of wine lovers -

pinotphiles.

2 The first wine publication to include ABV, pH, TA, and RS as part of informative wine reviews.

3 The PinotFile/Prince of Pinot website contained a unique Winery Directory with over 2800 winery profiles of

primarily domestic wineries focusing on Pinot Noir. This is the largest Pinot Noir winery directory on the

internet. There is a very large vineyard directory as well and wine reviews can be searched by winery name or

vineyard.

4 The latest news related to the Pinot Noir community was included in each issue in the Pinot Briefs section.

5 Updates and newest information on the relationship between wine in moderation and health was periodically

detailed and included summaries of scientific research.

6 Multiple terms were added to the Pinot Noir lexicon including pinotology, pinotosity, pinotspeak, pinotholicism,

pinot geek, pinot queen and pinot pimp.

7 Grape Radio podcasts at www.graperadio.com that were Pinot Noir related and involved the Prince were

accessible on the Prince of Pinot website.

8 The PinotFile was available free to subscribers as a noble and thoroughly redeeming accomplishment.

Fortunately, I had the financial base that my previous career provided me to proceed nobly.

My opinions expressed in the PinotFile were based on a vast amount of experience, but even though I was the

“Prince,” my judgements were never considered infallible or almighty. I certainly did not rule the world of Pinot

Noir. My departing advice is to explore the Pinot Noir kingdom and revel in all its diversity and current

excellence. And always remember, “If you drink no Noir, you Pinot Noir.”

There are so many people to thank who have supplied me with the necessary expertise and support to write

the PinotFile over the past 18 years. Steve Muller designed my first website and logo. David Isaacs managed

my website in the early years with dedication and a smile. Peter Rowell, with his technical know-how and

Wendy Coy, with her graphic design abilities, designed and helped maintain the modern version of the Prince

of Pinot website. Michael McDonald, another computer techie, assisted me over the past several years in

keeping the website running and trolling the immense amount of data therein to supply me with valuable

information. My son, Dane, who taught me everything I know about computers, faithfully posted every issue of

the PinotFile online for 12 years. Master Sommelier Rene Chazottes encouraged me and taught me integrity.

My wife, Patti, somehow had the patience to put up with my wacky devotion to a grape and has stuck with me

for 42 years. And finally, my mother Dorothy, who always said when I was a youngster that I would become a

doctor or a writer. Bless her heart, she was wrong, I became both.