Joe Rochioli Jr: No Ordinary Joe. A History of J. Rochioli Vineyards & Winery

“Rochioli remains the incontrovertible nexus of Pinot Noir in the Russian River Valley”

John Winthrop Haeger, Pacific Pinot Noir

Joe Rochioli Jr. (referred to as “Joe” in this article) is a winegrower extraordinaire, the patriarch of Russian

River Valley Pinot Noir farming. Ever humble but very proud, he has an indefatigable devotion to his vineyards.

His personal history is marked by numerous remarkable achievements that inseparably link him to the history

of Pinot Noir viticulture in the Russian River Valley.

Joe’s family history begins with his paternal grandfather who was born in San Vito, near Lucca, in Northern

Italy in 1874. At a very young age was left on a doorstep in town. The family that initially cared for him was

extremely poor and eventually sent him to an orphanage. Since he had no name, the orphanage gave him the

name “Michele Rocchioli” (“Mee-ke-le Ro-kee-o-lee”), a word that had no meaning in the Italian language. He

grew up unadopted and became a cobbler.

In 1896 Michel met Maria Assunta Catalani and married her in 1898. Joe’s father, Joe (Giuseppe) Rochioli Sr.,

was born to the couple in Northern Italy in 1902. He immigrated to the United States in 1912 at age eight years,

following in the footsteps of many other Italian-Americans who were to become notable families in the Sonoma

County landscape including, Bacigalupi, Martini, Martinelli, Pedroncelli, Pellegrini, Rafanelli, Sebastiani,

Seghesio and Simi.

Joe Sr. moved with his family to the Wohler Ranch located adjacent the Russian River near Healdsburg in

1914. The early history of the Wohler Ranch can be traced back to Captain Juan Batista Rogers Cooper, who

married General M.G. Vallejo’s daughter and was awarded the 18,000-acre Rancho Los Molinos as part of a

Mexican Land Grant. Cooper’s daughter Anna married Hermann Wohler in 1856 and the couple were given

1,320 acres that reached from near Forestville up river toward Healdsburg and included the land between

Westside and Eastside Roads.

Raford Peterson bought the Wohler ranch after Wohler died. He was the first in the county to plant hops (late

1890s) and became a major player in the county’s hop industry. Peterson hired hundreds of pickers and there

were several families of Italian immigrants who lived full-time on the ranch land including the Rochiolis. Wohler

Ranch became known as the Peterson Russian River Hop Ranch and was sold in the 1920s to W. C. Chisolm

who ran the ranch during the later years the Rochiolis lived there. Joe Sr. met Neoma Baldi and married her in

1930. Joe was born in 1934 in Sebastopol while Joe Sr. was working as a superintendent on the ranch. Joe’s

sister Violet was born the year prior and brother Michael in 1941.

In 1937, Mrs. Chisolm was not paying the Italian laborers, parcels were being sold, and Joe Sr. left for a

neighboring ranch known as Fenton Acres where the Rochioli family grew up. Solomon Walters and his wife,

who founded the Fenton Acres property, had come from North Carolina in a covered wagon in 1885 and bought

500 acres including a portion on Westside Road that Joe Sr. farmed. The large farm grew hops, grapes, prunes

and vegetables. Solomon’s son Billy and daughter Adelma Walters Fenton took over Fenton Acres when

Solomon passed away but eventually faced bankruptcy because there was little of money to be made selling

hops. They sold off portions of the ranch to Joe Sr. until by 1953 he would own 162 acres.

The Rochioli family lived completely off the land and was very poor. The family only spoke Italian at home so

that by the time Joe entered school at the age of six years he understood very little English. At the one-room

Mill Creek Grammar School located two miles up the road from their very modest home, Joe and his sister

were ridiculed for their lack of English, and because of their shyness, they had difficulty fitting in with the other

students. After school, Joe had to work on his father’s farm. He was pruning grapevines at the age of 8 years.

By age 12 years, he was doing a man’s work, lifting 60 pound sacks of hops in the hop kiln. When he entered

Healdsburg High School, he was 6-feet tall, weighed 160 pounds and wore size 12 shoes. His mother thought

there was something wrong with him because he grew so fast.

As a freshman in high school, the school’s football coach caught Joe fooling around and the coach promptly

ordered him to do 100 pushups. Joe quickly accomplished that task without breaking a sweat. The coach was

so impressed that he asked him to come out for the football team. Joe had no clue how to play football, yet he

was such a good athlete, he became a star player on both offense and defense. He also started playing

baseball his freshman year and earned all-league honors in both football and baseball all four years of high

school. He left high school as one of the greatest athletes to attend Healdsburg High School and was one of

the first athletes to be elected into the school’s Hall of Fame.

While at Healdsburg High School, Joe helped organize the first Future Farmer Fair in Healdsburg that is still

held today and was the president for both the Future Farmers of America and the Block H (athletic) Club. After

winning about every award offered in high school, he headed to Cal Poly San Luis Obispo in his 1941 Chevy himself. He majored in animal husbandry, but took all of the agricultural electives he could. This experience

piqued his interest in grapes and grape growing.

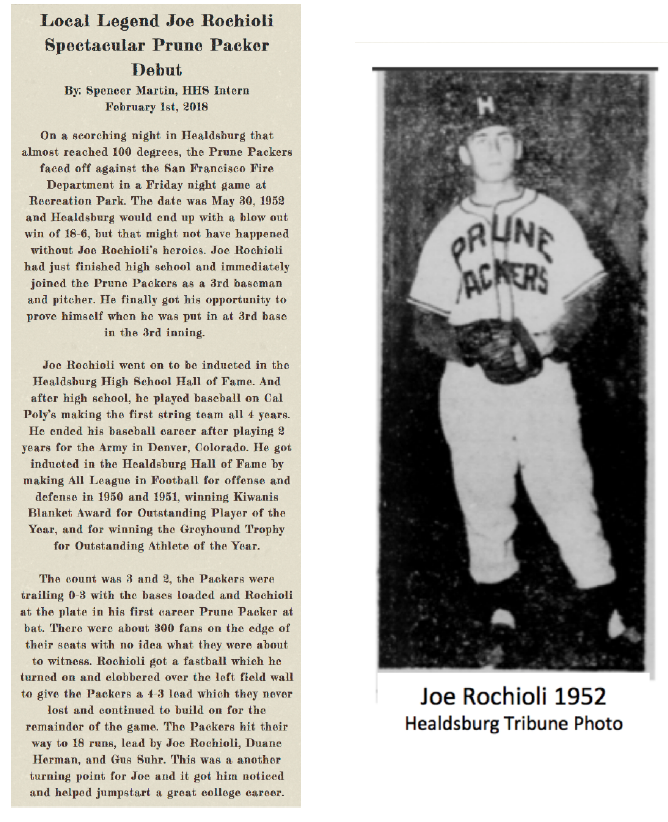

A Babe Ruth-like story has left a lasting legacy in Healdsburg sports lore. Joe had just graduated from high

school in 1952 when he was asked to join the Healdsburg Prune Packers semi-pro baseball team because he

led his high school team in hitting. He hit a grand slam home run the first time he got to bat and won the game

for the team. This story is documented at www.prunepackers.org

During the summers while attending college, Joe played semipro baseball for the Healdsburg Prune Packers

until 1957 when he was drafted into the US Army. Just before he was drafted, he married Ernestine Nicoletti.

While stationed at Fitzsimmons Army Medical Center in Colorado he did research on radiated foods and

vitamin deficiencies among K rations and also played baseball for the US Army. Upon his discharge in 1959, he

was offered a high-paying civilian job at the Medical Center, but his father expected him to return home to work

on the family ranch. Instead of the $10,500 annual salary he would have received for the civilian job, his father

gave him $1.00 an hour or barely $3,000 a year. He supplemented that income by playing semi-pro baseball

for ten years with the Healdsburg Prune Packers until they disbanded.

By the time Joe returned to his father’s ranch in 1959, the hops business had declined so significantly that his

father had removed all the hops and planted Blue Lake string beans. The hop trellises were simply lowered to

accommodate the new crop. The bean crop broke all state records for production and Joe Sr. became one of

the most prolific string bean growers in California.

The aged grapevines at the ranch had been ripped out in 1957 and in their place French Colombard and

Cabernet Sauvignon planted. Later, string beans were interplanted in the vineyard by digging a trellis out and

planting the beans on stakes, with two rows of beans between each row of grapevines. The string beans were

all pulled out by 1963. Joe considered the quality of the French Colombard superior to any other source in

Sonoma County, but the Cabernet Sauvignon failed to ripen. The French Colombard was sold to a few large

wine companies, particularly E.&J. Gallo.

Joe had taken over the grape growing at the ranch upon his return yet Joe Sr. was still clearly the boss. Some

Early Burgundy (Gamay Beaujolais) had been planted at the ranch in 1952 because it was prized for its high

yields and usefulness as a blending grape. Joe realized that it was impossible for the Rochioli’s Early Burgundy

and French Colombard grapes to compete price wise with the vast plantings of those varietals in California’s

Central Valley. In addition, Early Burgundy produced wines more like a rosé, and Joe would have none of that.

Joe has remarked, “No way was I going to plant that stuff.”

Joe was aware of the quality of French red Burgundy and had a hunch it would do well on the Rochioli

property. He knew that the land at the ranch had seven feet of fertile soil over gravel (Yolo sandy loam) making

it well-drained and he realized that the climate was compatible. He butted heads with his father and tried to

convince him to concentrate on quality French Burgundy varietals, specifically Pinot Noir. Joe believed that the

future of grape growing in the Russian River Valley lay in varietal wines rather than bulk wine blends that were

the norm at the time. His father was reluctant because the type of wine grapes used for varietally-labelled

wines produced small crops making them not as profitable.

Joe was persistent and his father finally relented, allowing him to plant Sauvignon Blanc in 1959. Joe traveled

to UC Davis where Sauvignon Blanc was planted to multiple clones. He walked the rows and tasted the

grapes, finding one row that tasted best. He took all the budwood off that row himself and budded plantings at

the Rochioli ranch. Joe was one of the first and most adept field budders. Until the 1970s, all grafting was done

by nurseries (so-called “bench graft”). With the widespread demand for vines, “field grafts” became the norm

and they required both time and patience. Joe was able to field graft at an extraordinary rate of 500 vines per

day and through the years budded practically every vineyard in Sonoma County. For years he traveled the

back roads in his 1947 International Harvester pickup truck, with a top speed of 25-miles-per-hour, working

tirelessly in other vineyards. Owners simply would not trust anyone else to do their field grafting.

The ten acres of Sauvignon Blanc vines Joe planted were so vigorous he had to trellis them on a double-

Geneva configuration. For years, the Sauvignon Blanc grapes were sold to Chateau St. Jean and other

wineries where it went into white blends. It wasn’t until 1969 that the Windsor Winery bottled Rochioli

Sauvignon Blanc as a distinct varietal. The original vines are still producing today but have been supplemented

by plantings of 2.8 acres of old vine cuttings in 1985 and of 3.4 acres of clone 376 in 2001. Rochioli Sauvignon

Blanc wines have won more awards than any other wine that Rochioli produces.

The Sauvignon Blanc vines at UC Davis were eventually pulled out and Joe was never able to obtain more of

the same budwood. The clone of Sauvignon Blanc planted originally at Rochioli Vineyard will forever remain a

mystery. Some of the old Sauvignon Blanc clone vines planted at Rochioli have been cleaned up by microshoot

tip culture at UC Davis allowing virus-free replantings.

As soon as Joe Sr. died in 1966, Joe bulldozed the eight acres of French Colombard and Cabernet Sauvignon

and set out to plant Pinot Noir. Joe was looking for a red variety that would do well in his cool climate, was

attracted to the potential for Pinot Noir, and the farm advisor recommended Pinot Noir as well. Neighbors

thought he was crazy at the time. Practically every maker of premium wines in the nearby Napa Valley in the

1960s produced a varietally-labeled and often vintage-dated Pinot Noir, but good examples were rare and often

underwhelming due to warm, misplaced vineyard sites and winemaking that was not appropriate for the Pinot

Noir paradigm. By the 1970s, with rare exception, California Pinot Noir was deemed unsuitable by many

wineries as a stand-alone varietal and those wineries ceased production of Pinot Noir.

There was no PInot Noir budwood available locally, so Joe sought out a Frenchman who reluctantly gave him

some “suitcase” French Burgundy budwood from the vineyard he farmed south of St. Helena in the Napa

Valley. The clonal type and origin of the vine source are unknown but most likely the clone was what is today

known as Pommard 4 and possibly included a field selection as well. In 1968, Joe planted 4 acres of East

Block Pinot Noir with cuttings from this vine source. The East Block was named for the area east of the

telephone pole on the property, one of the earliest, but not the first, plantings of Pinot Noir in the Russian River

Valley.

The Bacigalupi family had planted Pinot Noir on Westside Road in the Russian River Valley using budwood

acquired from the Wente brothers in 1964. Rodney Strong planted the River East Vineyard that included 19

acres of Pinot Noir adjacent his winery in Healdsburg in 1968. Joseph Swan put Pinot Noir in the ground in the

Vine Hill region of the Russian River Valley in 1969 with some of the budwood originating from Mount Eden.

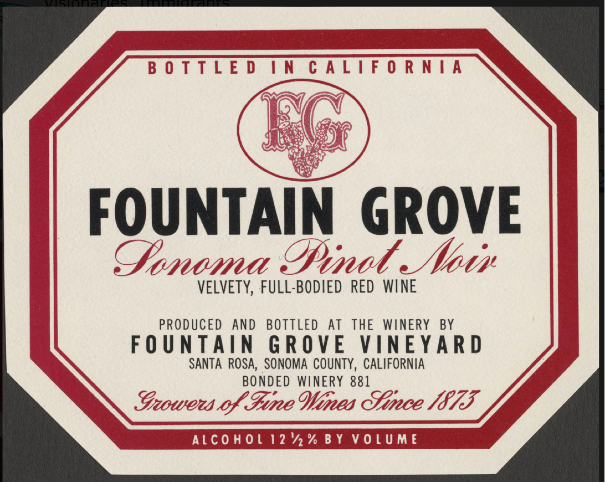

One caveat, pointed out by Steve Heimoff, in the book A Journey Along the Russian River, is that the

Fountaingrove Winery north of Santa Rosa, with operations from 1882 to the 1940s, reportedly planted Pinot

Noir in the Russian River Valley in the 1930s at an unknown location and produced a “Sonoma Pinot Noir.”

John Haeger, in his book North American Pinot Noir, reported that Fountaingrove bottled a Pinot Noir that was

100% varietal no later than 1936. The label below is from the 1940s.

In 1969, Joe acquired the shares owned by his brother and sister and became the sole proprietor of Rochioli

estate. The following year, 4 acres of West Block Pinot Noir were planted using budwood from either Karl Wente’s

estate vineyard in Livermore (presumably French clones) or from Wente’s UCD-certified plants in the Arroyo

Seco region of Monterey County (most likely a clone or field selection of Pommard 4). The exact clonal

pedigree of West Block plantings remains a mystery as vine morphology has not been confirmatory but it is

often concluded that the vines are Pommard.

The initial Pinot Noir plantings at the Rochioli property were typical for the time with a 14-foot spacing between

the rows and 8-feet spacing between the vines (see photos below of original West Block vines). The rootstock

was non-phylloxera-resistant AxR1.

The West Block Pinot Noir is often referred to as the “mother block” because cuttings from this block were used

for subsequent block plantings on the Rochioli ranch as well as many other vineyards in the Russian River

Valley including Allen Vineyard located across Westside Road from Rochioli vineyards. The original plantings

are referred to as Old Vine West Block. Currently, the West Block is about one-third of its original size but

newer plantings at West Block in 2008 added 2.5 acres of West Block selection. The original West Block

currently produces very little fruit but it has always been Joe’s favorite.

The first 3.5 acres of Chardonnay vines were planted on the Rochioli ranch in 1972 (clone 04 and 108 - a

combination of FPS selections 04 and 05) where the Little Hill Block currently resides. This acreage was part of

the wave of Chardonnay plantings in California in the early 1970s that reached a total of more than 7000

bearing and nonbearing acres by 1975.

Several blocks of additional Pinot Noir and Chardonnay were planted by Joe over the years. The virus-afflicted,

original vines at East Block were pulled out (last vintage 2008) and replaced with Pommard clone in 2010.

Many Rochioli wine enthusiasts begged Joe not to pull out the East Block vines, but at production levels of less

than one ton per acre, it simply did not make economic sense to preserve them.

Over the years there have been many challenges. The fog is a major factor in the successful growth of vines in

the Russian River Valley because it keeps the grapes cool in the evenings allowing for retention of natural

acidity. With that frequent fog, however, comes the threat of mildew. Joe says he has had to constantly monitor

mildew pressure and often has to spray for mildew every 10 to 14 days.

The proximity of the vineyards to the Russian River created vulnerability to voracious pests including bluegreen

sharpshooter and mealybug. More recently, a few vines in the Sweetwater Vineyard have tested positive

for grapevine red blotch disease (GRBD), a viral disease that leads to fruit ripening issues. These vines were

removed and replanted. Rigorous testing at Rochioli has found “clean” vines that are reserved for new

plantings.

Here is a summary to date of Pinot Noir planting acreage that makes up the majority of the 140 planted acres

at Rochioli Vineyards:

Three Corner Vineyard This 3.7-acre vineyard, located north of Rochioli Vineyard across Westside Road was

initially planted in 1974 by Joe using West Block bud material with later plantings also containing West Block

selection and Pommard 4 and Dijon 115 clones. Three Corner Vineyard was originally part of the Allen

Vineyard but was deeded to Joe by Howard Allen as a favor for farming the Allen Ranch for many years and is

one of the Rochioli estate vineyards. Total: 3.7 acres.

Little Hill Vineyard This vineyard lies adjacent West Block. 2.2 acres were originally planted in 1985 from

West Block cuttings. 1.8 acres of West Block selection and 1 acre of RC selection was added in 1994, 2.4

acres of West Block selection and 2.3 acres of Pommard clone were added in 2005, and 1 acre of West Block

selection and 5 acres of Pommard clone were planted in 2014. Total: 15.7 acres..

River Block Vineyard 13 acres of West Block selection were planted in 1988. 4.5 acres of clone 115, 4.5

acres of clone 777 and 4.7 acres of Pommard clone were added in 2000. Total: 26.7 acres.

Big Hill Vineyard. A rocky hillside site first harvested in 2011 and initially offered as a vineyard-designate Pinot

Noir with the 2016 vintage. The Rochiolis consider this vineyard the “Grand Cru” of the entire estate because of

the ideal red gravelly loam soil and the southern exposure. The Pinot Noir wines have more structure than

those from other blocks and offer more complexity and interest, that is, a little less fruit emphasis and more

“Burgundian” in character than typical Russian River Valley Pinot Noir. Big Hill Vineyard wines have garnered

the highest scores among all Rochioli Pinot Noirs. 3.8 acres of West Block selection and 0.8 acres of Calera

selection planted in 2009. Total: 4.6 acres.Noirs.

Sweetwater Vineyard 2.9 acres of clone 115 planted in 1994, 3.6 acres of clone 777 planted in 1999, 4.7

acres of West Block selection added in 2000 and 2017,1.5 acres of Pommard clone planted in 2014, and 1.6

acres of Calera selection in 2017.

Total: 14.3 acres.

Summary of additional plantings: 30 acres of Chardonnay (Mt Eden selection, Wente selection, Hanzell

selection, Clone 4 and 108, Dijon 5, 76 and 95) is planted in River Block, Little Hill Block, Sweetwater Vineyard

and what is known as the Mid-40 Block. 7.2 acres of Sauvignon Blanc is planted in the Little Hill Block and

Mid-40 Block. There are tiny plantings of Syrah, Cabernet Sauvignon and Valdiguié.

A map of the entire Rochioli Vineyard is displayed below and can be accessed on the Rochioli website for

easier readability.

The first viable Pinot Noir crop from the original plantings was in 1971 and the grapes were sent to a cooperative

crush facility owned by E.&J. Gallo in Windsor. Most of the grapes from Russian River Valley

winegrowers went into what Joe has called “Gallo garbage.” There were simply few buyers for the grapes. Joe

recalls how sick he became when he had to send his beautiful Pinot Noir grapes from East Block and West

Block to Gallo, who then proceeded to blend them with other grape varieties from the Sonoma, Napa and

Central valleys to make his highly successful Hearty Burgundy

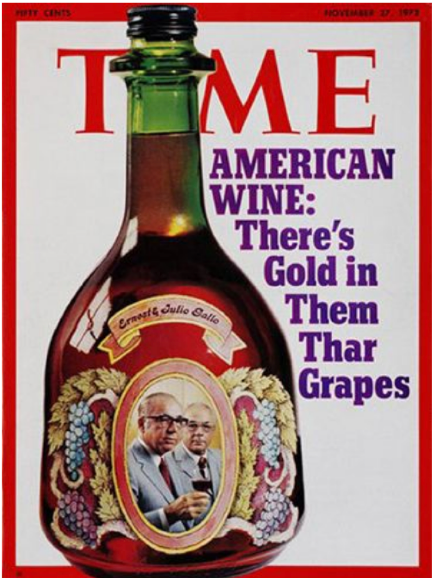

Hearty Burgundy was first released in 1964 in 1.5 liter “jugs” and was non-vintage dated. I have fond memories

of Hearty Burgundy for it was my father’s favorite wine. It graced our family dinner table on many occasions,

and was a frequent accompaniment to pizza when we dined at his favorite neighborhood Italian restaurant. The

exact composition was a trade secret, but it was believed to be a blend of Zinfandel, Tempranillo, Syrah, Petit

Verdot, Grenache, Petite Sirah, Cabernet Sauvignon and briefly, Joe’s Pinot Noir. Winemaker Stephen Russell,

a UC Davis enology graduate who went to work at Gallo in 1960, recalls, “The mixture of almost any grape

available at the time was challenging to produce because the goal was to make Hearty Burgundy taste

consistently the same, although the types and sources of grapes varied widely with each vintage.”

In Ellen Hawkes book, Blood & Wine, The Unauthorized Story of the Gallo Wine Empire, she states, “Hearty

Burgundy was praised by some critics for its depth and complexity, and even gained popularity among ‘wine

snobs’ who usually scorned the Gallo label.” Hearty Burgundy graced the cover of Time magazine in 1972, an

issue devoted to the booming California wine industry. They weren’t kidding when the magazine cover claimed,

“There’s Gold in Them Thar Grapes,” because Joe prized fruit was in the blend. In 2014, a commemorative

bottling was offered for $9 celebrating the wine’s 50th anniversary.

In the 1960s, grape farmers in Northern California were not organized and were being victimized by Gallo and

a few other large wineries who controlled prices that were determined after the receipt of grapes, so-called

open-price contracts. The growers would deliver their grapes to Gallo in September without knowing what they

would be paid. In December of the vintage year, before property taxes were due, the farmer would receive a

check in the mail from Gallo that amounted to whatever Gallo wanted to pay. In 1963, Joe helped form the

North Coast Growers Association (NCGGA) to give small wine grape growers a voice in dealing with the large

company buyers. After a considerable amount of effort spread over several years, the NCGGA lobbied in

Sacramento and the state eventually passed legislation that eliminated open-price contracts. An upfront

agreement on the price wineries would pay the winegrowers for their grapes became the law. The NCGGA

forced Gallo to commit to paying $100 a ton with a $5 a ton bonus if the grapes were really premium.

Joe had acquired some contracts for his grapes including Dry Creek Winery and Chateau St. Jean who bought

his Sauvignon Blanc grapes. He was selling his Pinot Noir to Korbel for their sparkling wines and to Wente and

Gallo for their blended wines. As he looked for someone to produce a varietal Pinot Noir from his grapes, good

fortune was to arrive in the form of a fledgling winery a few miles away on Westside Road.

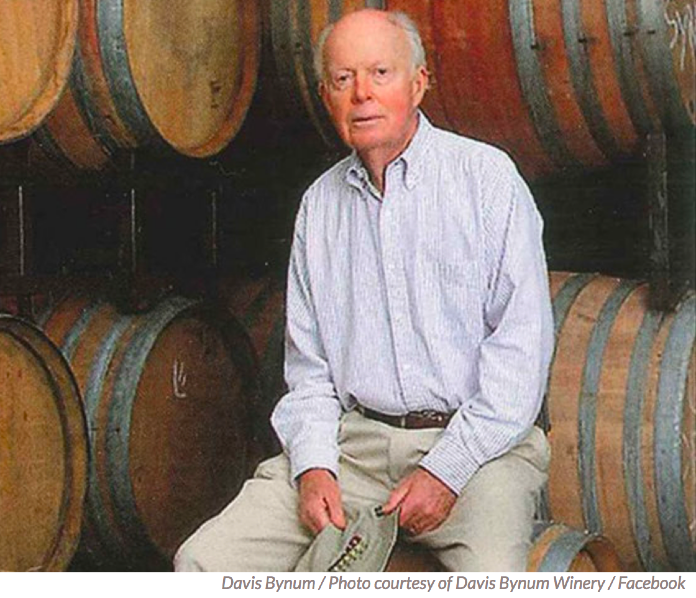

In 1972, Davis Bynum, a San Francisco newspaper journalist, home winemaker, and the son of noted

California wine writer, Lindley Bynum, bought the 84-acre River Bend Ranch on Westside Road for a reported

$115,000. The property had a hop kiln used for drying hops and Bynum converted the hops processing room

next to the kiln into a winery and launched Davis Bynum Winery. Bynum developed several handshake

agreements with local winegrowers to acquire grapes include Joe, Howard Allen and Rick Moshin but he was

particularly enamored with Rochioli fruit. He bought Rochioli’s Pinot Noir in 1973 and from 1973 to 1979 (?

1981) was the only winery receiving Rochioli fruit. Bynum recalled in an 2013 interview that in 1973 Rochioli

was getting $150 a ton for Pinot Noir. He offered $350 (also reported to be $450) to make a varietal wine and

got all of Rochioli’s Pinot Noir that vintage. Bynum’s son Hampton and consultant Robert Stemmler, a

pioneering Pinot Noir winemaker in Sonoma County, crafted the wine at Davis’ winery. Davis Bynum, who

passed away in 2017, is shown in the photo below.

The 1973 Davis Bynum Winery Rochioli Vineyard Russian River Pinot Noir and the 1973 Joseph Swan

Russian River Pinot Noir were probably the first Pinot Noirs to carry the words “Russian River” on the label, ten

years before the Russian River Valley AVA was approved. Bynum’s 1973 wine was the first Russian River

Valley vineyard-designated Pinot Noir. The label read, “From the vineyard of Joseph Rochioli Jr. on Westside

Road in the Russian River” Despite the historical significance of the 1973 Pinot Noir, Joe claims the 1978 Davis

Bynum Rochioli Vineyard Russian River Valley Pinot Noir is the best Pinot Noir he has ever tasted.

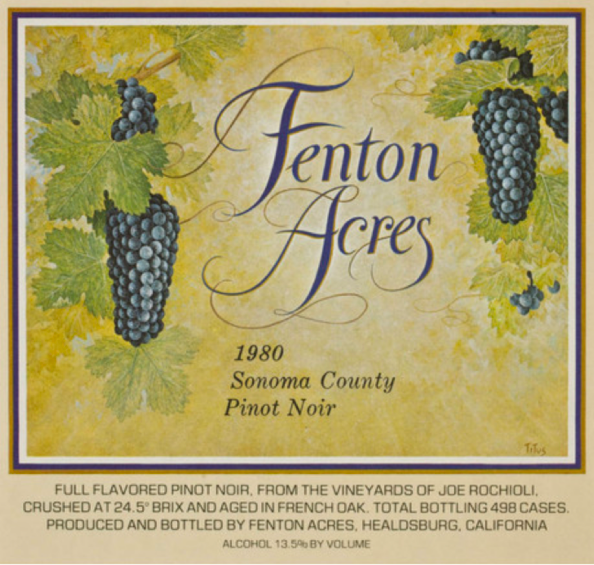

Beginning in 1976, Joe had Davis Bynum produce 1,000 cases of Pinot Noir. He then joined with two partner

investors to increase production at Davis Bynum Winery to 2,000-3,000 cases of Pinot Noir and Chardonnay.

The wines were bottled under the Fenton Acres label, referencing the original name of the Rochioli property.

The label stated, “Sonoma County Pinot Noir” with “From the Vineyards of Joe Rochioli” in fine print on the

bottom. The wines proved to be a tough sale, the partners soon lost interest in the venture, and the partnership

was dissolved.

Gary Farrell, who vinified the Fenton Acres wines as a winemaker at Davis Bynum Winery, would play a vital

role in validating the Russian River Valley as an exceptional region for domestic Pinot Noir and in assisting the

Rochiolis in establishing their own winery. Farrell had majored in political science at Sonoma State University

but became interested in wine as a student and decided after to college to become a winemaker. He was

largely self-taught, but he added valuable skills during the mid-1970s, working in the cellars of Tom Dehlinger,

Robert Stemmler and Davis Bynum. He developed a special friendship with Davis Bynum’s son, Hampton, and

was hired as winemaker at Davis Bynum Winery in 1978, continuing there until 2000.

Farrell started his own label in 1982, releasing a 50-case blend of Rochioli West Block and North Hill of Allen

Vineyard fruit. Farrell has said, “It (Rochioli Vineyard) confirmed my opinion that world-class Pinot Noir could be

grown in the Russian River Valley.” The wine sold for a modest $80 a case because there was little demand for

Russian River Valley Pinot Noir at the time and he had to hand-deliver the wine to local retailers and

customers. Farrell’s wines soon took on considerable praise and won many awards. I remember fondly drinking

many Gary Farrell Russian River Valley Pinot Noirs from the 1980s.

Joe’s son, Tom, was most instrumental in establishing the J. Rochioli Vineyards & Winery wine brand. He had

become disenchanted with his job in corporate banking at Bank of America in Santa Rosa leading him to ask

his father if he could work on the Rochioli ranch. He suggested that the name Rochioli should be the wine

brand rather than Fenton Acres to signify a family operation. Tom put together a business model for

a 10,000 case winery and he was taken in as a partner and winemaker. Every aspect of the winery business going forward was Tom's creation. The photo below shows father and

son, what I call “No ordinary Joe” and “No typical Tom”.

Tom had no formal training in winemaking so Farrell was asked to make 150 cases of the inaugural 1982 J.

Rochioli Vineyards & Winery Rochioli Vineyard Pinot Noir, trading winemaking for grapes he used for his own

1982 inaugural release. That now historic 1982 J. Rochioli Vineyards & Winery Russian River Valley Pinot Noir

label is shown below.

Tom learned quickly from Farrell but he also had an intuitive sense about how Rochioli fruit should be handled.

Using Tom’s business acumen and winery design input from Gary Farrell, a winery was constructed on the

Rochioli estate in time for the first crush at Rochioli in 1985. In 1987, the Wine Spectator named the 1985 J.

Rochioli Vineyards & Winery first estate Pinot Noir crafted primarily by Tom at the new winery as the “Best Pinot Noir in

America.” Tom has remained the winemaker at Rochioli since 1986. The winery was remodeled with specific

rooms for red and white wine production and was finished in 2009.

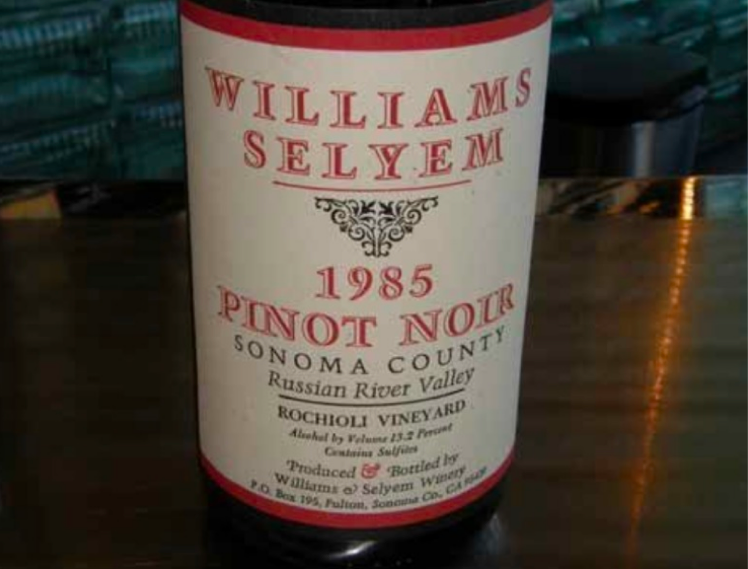

Burt Williams of Williams Selyem Winery was an additional inspirational winemaking influence on Tom and it

was Williams Selyem that made Rochioli Vineyard famous, In 1987, the 1985 vintage Williams Selyem Rochioli

Vineyard Russian River Valley Pinot Noir, vinified at a 900-square-foot two-car garage in the tiny Russian River

Valley town of Fulton, won a Double Gold Medal and the Sweepstakes Award at the California State Fair

Competition and became the most seminal wine in the history of California Pinot Noir. The wine was voted the

best of 2,316 wines submitted by 416 wineries. As the first vineyard-designated Pinot Noir produced at

Williams Selyem, this wine was sourced from the original West Block plantings but this was not evident on the

label. 295 cases of this wine were produced and it sold for $16 a bottle. Williams Selyem was also voted

“Winery of the Year.”

When Burt reminisced about this award, he would nearly tear-up, saying, “Here was this little winery in a

garage competing against over 400 wineries in the wine competition, many of which were quite large. When we

released our 1985 Pinot Noir, we knew we were doing something right.” In 1987, Becky Wasserman a well-known

Burgundy exporter, along with Burgundy vignerons, visited Williams Selyem and asked for 50 cases of

the 1985 Rochioli Vineyard Pinot Noir! She only received 1 case but did get 25 cases of the 1986 vintage of

the same wine and it began showing up on wine lists in Burgundy.

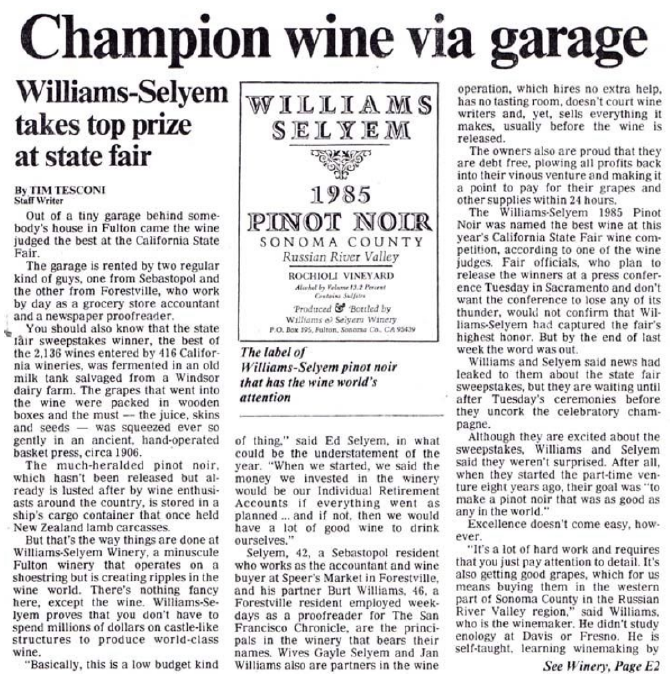

An article appeared in the June 27, 1987, business section of the Santa Rosa Press Democrat announcing the

top prize won by Williams Selyem (copied below). Note the incorrect name of the winery in the article, for the

two names were never hyphenated. Williams Selyem continued to source West Block fruit until the winery was

sold in 1997 after which time Williams Selyem has received old and new plantings from the River Block.

The demand for Rochioli fruit soon took off and Joe was able to demand premium prices for his grapes. He

continued to mainly sell fruit to Williams Selyem and Gary Farrell at Gary Farrell Vineyards & Winery and his

second venture Alysian Wines, and for years these two wineries were the only ones permitted to put “Rochioli

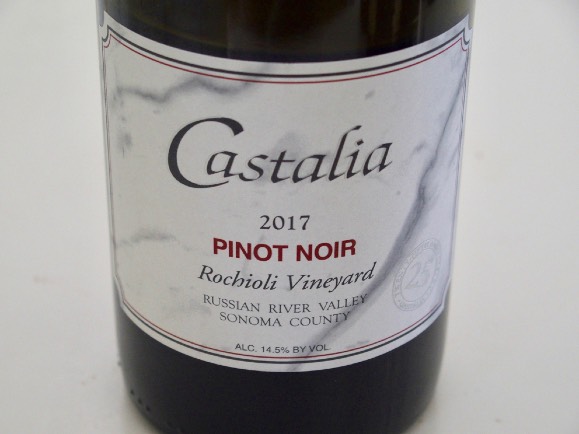

Vineyard” on their label. Today, the permission has been extended to Miura, Ramey Wine Cellars and to Terry

Bering for his Castalia label. Terry has been the cellar master at J. Rochioli Vineyards & Winery since 1990

(and the only full-time employee outside of Tom in the cellar), and in 2019 Terry released his 2017 Pinot Noir

sourced from Rochioli fruit, marking his 25th-anniversary producing Rochioli Vineyard Pinot Noir. I have

reviewed the excellent Castalia Pinot Noir wines in the PinotFile going back to 2000.

Rochioli Chardonnay is currently sold to Williams Selyem, Gary Farrell Vineyards & Winery and Ramey Wine

Cellars. A plump cluster of Rochioli Chardonnay is shown in the photo below.

A number of other wineries have sourced Rochioli fruit through the years but there are many other notable

small prestigious producers of Pinot Noir in California who have begged for fruit but had to resort to joining a

long waiting list. Joe has told inquiring wineries they will never get any grapes, but they insist on putting their

name on the waiting list anyway. Cuttings from Rochioli vines are no longer sold or given away. A beautiful

cluster of West Block Pinot Noir is shown below in a photo.

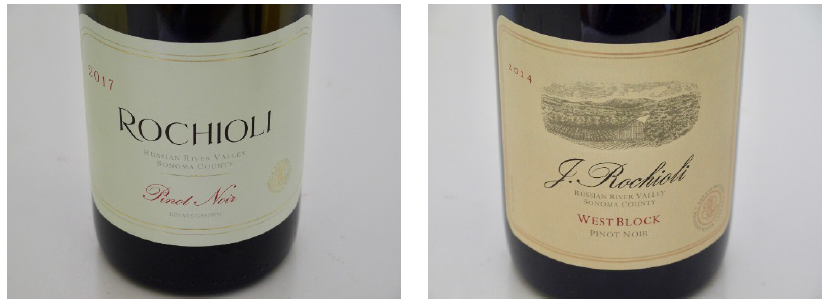

The Estate blends of Pinot Noir, Chardonnay and Sauvignon Blanc are bottled under the Rochioli name, while

the single-block vineyard-designated Pinot Noirs and designated Chardonnays are labeled as J. Rochioli

Vineyards & Winery. The classy labels have remained essentially the same through the years. Beginning with

the 2018 vintage, the back label of the “Estate” wines will state “Single Vineyard Blend” to more accurately.

An Estate Pinot Noir has been produced every year since 1982. It is a blend of grapes from all of the single

block vineyards except Three Corner. A Reserve Pinot Noir, consisting of a selection of barrels from the West

Block was produced in 1986, 1988, 1990 and 1991. In 1988, it was labeled as Special Select. In 1992, the first

of the block designates debuted with the West Block and Three Corner Block Pinot Noirs. East Block was

released separately in 1993, 1994, and then yearly from 1997 to 2008. Little Hill Block and River Block debuted

in 1999 and the Sweetwater Vineyard Pinot Noir was first offered in 2007.

The five original single-block Pinot Noirs - East Block, West Block, Three Corner, Little Hill and River Block -

were first offered together in 1999. Tom had visited Burgundy (Joe never did) in 1990 and was struck by the

differences in the wines from the seven climats at Domaine Romanée-Conti (DRC). Tom has said, “Here are

these blocks of vines together in a small area on a slope that looks fairly uniform, yet the wine from each plot is

unique and different.” Both the quality and the distinctness of the DRC wines led to his epiphany.

Tom had noted differences in barrels from different blocks on the Rochioli estate despite a majority of the vine

material originated from West Block cuttings, cultivation was identical throughout the five blocks, and the

vinification was the same for each plot. Each wine was recognizably distinct, reflecting differences in terroir

similar to the subtle disparities in soil and microclimate that define the distinct terroirs at DRC and those of

Burgundy’s Côte d’Or.

The specifics of the inaugural release of all five 1999 J. Rochioli Block Pinot Noirs: East Block - 1.2 tons per

acre, 150 cases, $85; West Block - 1.6 tons per acre, 400 cases, $65; River Block - 150 cases, $55; Three

Corner - 100 cases, $55; Little Hill - 200 cases, $50.

Production has varied since 1999 because some of the old vines have been replaced periodically, older

plantings have had lower yields as newer plantings have come online, and in some vintages, not every block designate

was bottled. The current target is 12,000 cases annually and this has been relatively consistent in

recent years. The single-vineyard Pinot Noir and Chardonnay wines account for about 3,000 to 4,000 cases

with the remainder made up of Estate (Single Vineyard Blend) Pinot Noir, Chardonnay and Sauvignon Blanc.

Tom says, “We are not trying to get bigger, just better!”About 50% (180 tons) of grapes harvested at Rochioli

each year are sold to other wineries.

Farming such a large estate is daunting. A crew of men who have worked on the property for many years have

provided familiarity with the vines. The crop is thinned as many as five times during the growing season

beginning with suckering in early spring and the removal of green grapes during veraison. Joe was one of the

first winegrowers to drop leaves on the sunny (west) side of the vines and this process is widely practiced in

California vineyards to this day. The ongoing replacement of old vines entails additional labor.

Tom has directed most of the new planting over the past 20 years in addition to his duties as winemaker and business manager.

More recently, as part of a continuing preservation process, the winery has begun to use the techniques of Simonit &

Sirch, wine master pruners for many famous vineyards in Burgundy. The Rochioli staff has been trained to

properly prune vines to insure restoration and preservation of the historic vines that will allow them to live a

long life, potentially up to 50 years.

Joe was a tireless and devoted farmer who would arise at 4:00 A.M. and work 10 hours a day, 6 days a week.

He has told me, “I was never in it to make a lot of money, I did it for pride. When somebody asks how we do it, I

answer that it’s the combination of soil, climate, clones, instinct and farming practices.” He spurned vacations

and rarely left his property.

Joe performed most all of the equipment repair required on his farm including welding. He built many of his

own implements, rebuilt engines, restored plows and cultivators, and designed farming tools like cane cutters.

Remarkably, he even built his own house over the course of three years using a $15,000 loan from a wealthy

Santa Rosa businessman (his son Tom now resides in the house located on the Rochioli property).

Despite Joe’s devotion to his vineyard, he did find time to give back to the community. He served sixteen years

on the Westside Union Elementary School Board and twenty-five years on the Healdsburg Future Farmers Fair

Board of Directors. He was one of the founding members of the Healdsburg Fair, dedicating decades to

support youth in agriculture. He has also been a member of the California Farm Bureau for over fifty years.

Joe has received numerous accolades and awards over the years. In October 2009, he received the

Lifetime Contributor to Sonoma County Agriculture Award, and in October 2017, he was given the “Methuselah

Award” for his lifetime contributions to Sonoma County’s wine industry. Tom has also been honored by the wine

establishment. As part of the 2016 Sonoma County Barrel Auction, Tom was one of four icons, along with Helen

Bacigalupi, Tom Klein and David Rafanelli, honored for their role in shaping the heritage and history of Sonoma

County wine. The four icons are pictured below with Tom in the center.

The years of hard work have taken a toll on Joe, but after many surgeries, at age 86, he still acts in a

supervisory capacity overseeing the vineyards. Joe was divorced in 1969 and married Vivienne Sioli, the girl he

adored in high school (the couple are pictured below). Joe had two previous children, she had three, and

between them, they have eleven grandchildren. Joe, in the Italian tradition, hosts frequent family dinners on the

weekends with nearly forty family members in attendance.

Joe has preserved much of his history including his father’s horse saddles and horse carriage, a restored

Model T truck, and his prized, restored 1941 Chevrolet that he drove in college, all housed in a 60’ x 60’ barn.

Joe is no ordinary Joe and his superb wines reflect his years of devotion to the craft of winegrowing. I have

never met anyone like him and after reading this lengthy history, I don’t think the reader will ever discover

another winegrower with such a remarkable story to tell. Joe’s history is best summarized in his own words.

“My father taught me the ethic of hard work - you work hard to eat and put a roof over your head. I used to

dream about living to be 65 and being a millionaire. I’ve ended up with a great winery and good friends, and I

am proud of what I’ve accomplished as a shy, little Italian boy who spoke no English.”

References:

Multiple interviews with Joe published previously in the PinotFile.

Personal conversation with Tom Rochioli.

Healdsburg’s Immigrants: An Anthology of 24 Local Histories, collected and edited by Shonnie Brown, 2015.

A Wine Journey along the Russian River, Steve Heimoff, 2005.

Pacific Pinot Noir, John Winthrop Haeger, 2008.

“I’ll Drink to That” - Levi Dalton interview of Joe Rochioli, Jr, Episode 466, vinography.com

Joe Rochioli, Jr. on VIMEO: https://vimeo.com/22672188