Drinking Oregon Pinot Noir History from Old Vine Vineyards

Elk Cove Windhill Vineyard 1974 planting of Pommard own-rooted vine (2020)

“We prize those own-rooted old vines for their stability, consistency,

complexity, aromatic intensity, and length on the palate.”

Adam Campbell, Elk Cove Vineyards

Contents

Acknowledgements p 3

Introduction p 5

List of Reviewed Willamette Valley Old Vine Pinot Noir Wines p 9

List of Willamette Valley Pinot Noir Vineyards by Year of Original Planting 1965-1979 p 13

Vineyards Established 1965-1969 p 16

Vineyards Established 1970-1971 p 24

Vineyards Established 1972 p 39

Vineyards Established 1973 p 51

Vineyards Established 1974 p 61

Vineyards Established 1975 p 71

Vineyards Established 1976 p 75

Vineyards Established 1977 p 82

Vineyards Established 1978-1979 p 89

Other Willamette Valley Vineyards Planted in the 1970s p 97

Four Willamette Valley Vineyards with Interesting Histories Established 1981-1983 p 98

Old Vine Quotes p 104

Epilogue: Pommard in Guise p 105

Acknowledgements

Legends

David Adelsheim, founder of Adelsheim Vineyard

Dick Erath, co-founder of Knudsen-Erath Winery and founder of Erath Winery

Bill Fuller, founder of Tualatin Vineyard

Winegrowers & Winery Principals

Peter Adams, Adams Vineyard

David Adelsheim, Quarter Mile Lane Vineyard

John Bangsund, Bangsund Vineyards

Ian Burch, Archibald and Arcus Vineyards

Margy Buchanan, Tyee Estate Vineyard

Adam Campbell, Elk Cove Vineyards

Claire Carver, Big Table Farm

Christina Collins, Sokol Blosser

Tabitha Compton, Compton Family Cellars

Bruno Corneaux, Domaine Divio

Dai Crisp, Temperance Hill Vineyard

Dyson DeMara, HillCrest Vineyard

Page Knudsen Cowles, Knudsen Vineyard

Pat Dudley, Bethel Heights Vineyards

Bill Fuller, Tualatin Vineyard

Barbara Gross, Cooper Mountain Vineyards

Steve Hendricks, Beran/Ruby Vineyard Janie Heuck, Brooks Estate Vineyard

Patrick Hickock, Northwest Wine Co (Hyland Vineyard)

Kevin Johnson and Beth Klingner, DION Vineyard

Mike Kuenz, David Hill Estate Vineyards and Wirtz Vineyard

Jason Lett, The Eyrie Vineyards

Dominique Mahe, Saucy/Juliard/Furioso Vineyards

Martha Maresh, Maresh Vineyards

Kerry McDaniel Boenisch, McDaniel Vineyard, Olson Estate Vineyard

Donna Morris and Bill Sweat, Winderlea Estate Vineyard

Brian O'Donnell, Belle Pente Vineyard & Winery

John Paul, Cameron Winery

Luisa Ponzi, Ponzi Estate, Abetina and Abetina 2 Vineyards

Scott Robbins, Woodhall III Vineyards

Steve Vuylsteke, Oak Knoll Vineyard

Mark Wahle, Wahle Vineyard

Bill Wayne, Abbey Ridge Vineyard

Vivian Weber, Weber Vineyard

Amy Wesselman, Oracle Vineyard

Luci Wisiniewski, Sunnyside Vineyard

Scott Zapotocky, Eola Springs Vineyard

Helpmates

Sarah Murdoch, Oregon Wine Board, Director of Communications.

Emily Patterson, PR for Willamette Valley Wineries Association

Rich Schmidt, Director of Archives and Resource Sharing, Linfield College

Internet

Linfield College Oregon Wine History Archive, www.oregonwinehistoryarchive.org

Oregon Wine History, www.oregonwine.org

Oregon Wine History, www.oregonwinehistory.com

Publications

Dirt+Vine=Wine: How grape growers shaped an Oregon pinot noir revolution, Kerry McDaniel

Boenisch

North American Pinot Noir and Pacific Pinot Noir, John Winthrop Haeger

Oregon Wine: A Deep-Rooted History Scott Stursa

Oregon Wine Press

The Old Vines of Oregon Wine, Paul Gregutt, Wine Enthusiast, 08/07/2017

Vineyard Memoirs,Kerry McDaniel Boenisch

Winemakers of the Willamette Valley: Pioneering Vintners from Oregon’s Wine Country, Vivian Perry

and John Vincent

Introduction

Hyland Vineyard Old Coury “Clone” Pinot Noir Vines in Jory Soil

“Vine age is the key to balance. There’s no substitute for wine age.”

Ted Lemon, Winemaker Littorai

There is no consensus or legal definition of “old vine” Pinot Noir. Wikipedia states, “In a place where wine

production is longstanding, it often means a wine whose vines are thirty to forty years old.” The term “old vine”

has been debated for years in the wine industry and the term “mature vine” has been suggested as an

alternative.

Most winemakers believe the terminology should be defined and regulated. Some would argue that “old vine”

grapes should make up at least 85% of the grapes contained in a wine sold as “old vine,” while others prefer

that 95% of the grapes be from old vines.

There are significant variances to consider among different varietals as well. For example, Pinot Noir vineyards

over 20 years of age are considered by many “old”, yet Zinfandel from a 20-year-old vineyard would not be

considered “old vine.”

For this extensive review of producing old vine Willamette Valley Pinot Noir vineyards, I have chosen 42 years

as a cutoff, that is, vineyards originally planted before 1980. There are a precious few of these old vine Pinot

Noir vineyards that are still productive in Oregon’s Willamette Valley. This is primarily due to phylloxera, a root-eating

aphid that caused the demise of many of the widespread own-rooted plantings of Pinot Noir established

in the fifteen years prior to 1980 when it made the most sense to plant vines on their own rootstocks. As Jason Lett pointed out to me, own-rooted vines have more disease resistance, better water use efficiency, and more natural ratios of sugar to acid among other advantages.

Phylloxera infestation first began to appear in the early 1990s in the Dundee Hills, the epicenter of early

Willamette Valley Pinot Noir plantings. A November 1995 publication by the Oregon State University Extension

Service titled “Phylloxera Strategies for Management in Oregon's Vineyards" stated that phylloxera was then in

every major grape-producing region in Oregon. As vineyards succumbed to phylloxera, original plantings were

often removed and replanting was undertaken with phylloxera-resistant rootstocks.

I was able to verify that currently there are only 41 surviving over 40-year-old Willamette Valley vineyards

composed of predominantly or totally original own-rooted plantings of Pinot Noir still in significant production.

The Willamette Valley old vine vineyards that have survived were often planted properly to begin with, were not

tilled, were relatively isolated with restricted access, often managed with proper sanitation, and lovingly farmed

by owners who avoided using vineyard equipment from other vineyards and employing outside vineyard

workers. A majority of surviving vineyards are in the Dundee Hills AVA.

The 1970s were a plentiful time for vineyard plantings in the Willamette Valley. The impetus was the mid-to-late

1960s plantings by California transplants David and Diana Lett (The Eyrie Vineyard), Charles Coury (Charles

Coury Vineyard), Dick and Nancy Ponzi (Ponzi Estate Vineyard), and Dick Erath (Chehalem Mountain

Vineyard). The history of the first plantings of Pinot Noir and Pinot Gris at The Eyrie Vineyard have been well-documented

in the PinotFile: www.princeofpinot.com/article/1090/ The history of the roles of Coury and

Erath in the widespread planting of the Coury “clone” can be found at www.princeofpinot.com/article/1214/.

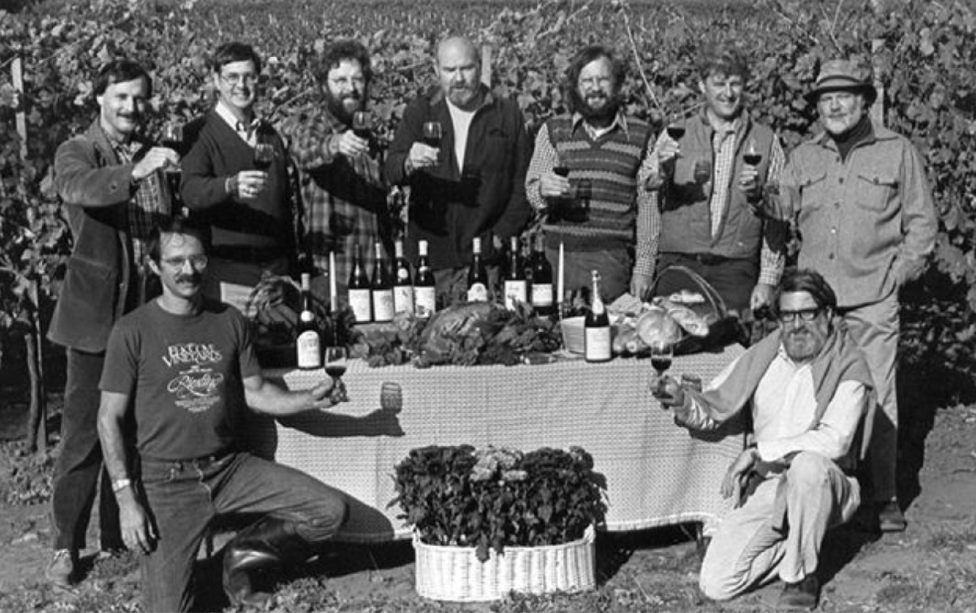

Wine Pioneers pf the Willamette Valley: Clockwise - Joe Campbell (Elk Cove), Bill Blosser

(Sokol Blosser), Don Byard (grower), Dick Erath (Knudsen-Erath)yron Redford (Amity Vineyard), Fred Arterberry

(Arterberry Maresh), Fred Benoit (Chateau Benoit), David Lett (The Eyrie Vineyard), and

David Adelsheim (Adelsheim Vineyard)

Most recently, David Adelsheim, a pioneering Willamette Valley winegrower, shared invaluable information with

me through personal communications about the early clonal plantings of Pinot Noir in the Willamette Valley.

This information is detailed below. Read more about this icon at www.princeofpinot.com/article/1418/.

Many of the Willamette Valley winegrowers of the 1970s did not keep good records and therefore adequate

documentation of the original planted clone or selection is unavailable. There were three heat-treated and

certified Pinot Noir clonal options available from FPS at the time: Pommard UCD 5 and 6, Martini UCD 13 and

15 (more widely planted in California), and Wädenswil UCD 1A and 2A.

“Gamay Beaujolais” type clones (particularly UCD 18 and 22), a distinct sub-clone of Pinot Noir and upright in

growth (pinot droit), were also available from the FPS. This was a group of five selections known as GB that

came to FPS in the early 1960s from a single vine in an old vineyard on the campus of UC Davis. The five

selections were FPS 18 (most common in Oregon), 19, 20 (dropped), 21, and 22.

Jason Lett’s research would indicate that the cuttings his father obtained from Wente in California in 1965 were

Wädenswil UCD 1A (not UCD 2A). Many of the early plantings of the Wädenswil clone in the Willamette Valley

were taken from Lett’s vineyard or descendant vines from that vineyard. There was an early heat-treated

version of Wädenswil, UCD clone 2A, named UCD clone 30. Erath may have brought UCD 30 to Oregon and

propagated vines for himself and others. UCD clone 30 was not widely propagated in Oregon or California

partly because of how the name was shown in the Foundation vineyard list of scion material. It appeared under

the variety name “Pinot Noir Blue Burgundy” not just “Pinot Noir”), and it was shown under a completely

unrelated clone number from its mother vine, clone 2A.

The Pommard clone was the first Pinot Noir clone distributed by FPS (renamed FPMS in 1958) in the 1950s

and became a workhorse in California vineyards by the 1970s and accounted for ࡪ of Oregon Pinot Noir

plantings prior to the arrival of the Dijon clones in the late 1980s. The Pommard clone was brought to Oregon

by Erath and Coury as part of their nursery partnership that started in 1970, then dissolved in 1971, with Coury

continuing and Erath starting his own nursery in 1973. Together, they obtained other Pinot Noir clones from

FPMS including Mariafeld (UCD 23), Martini (UCD 13 and 15), and Jackson (UCD 09 and 16), but none of

these were widely planted in Oregon.

Coury sold scion materials from his nursery in Oregon that purportedly were Pommard, but incorrectly

designated by him in an effort to keep up with the demands for Pinot Noir scion material at the time. These

selections became known as the “Coury clone” and were widely planted in the Willamette Valley in the 1970s.

They are thought to represent one or more suitcase selections of Pinot Noir brought surreptitiously into the

United States by Coury from Alsace France, and are not a true clone or the same as the Pommard clone. In

addition, Coury’s nursery offered 23 kinds of Vitis vinifera, some of which also turned up in the cuttings Coury

sold as “Pommard”.

Bill Wayne, the founder of Abbey Ridge Vineyard in the Dundee Hills, related the following history to me.

“About 1982 I was looking for cuttings of the Pommard clone to expand my vineyard in the Dundee Hills. In

1978, I had bought some “Pommard” from Dick Erath’s nursery, and after a few years, noticed that there were

a lot of “rogue” vines mixed in: Gewürztraminer, a weird late-ripening variety, etc. So when I needed more

Pommard, I got some cuttings from Hyland Vineyard and my friend Jack Trenhale, expecting that they were

more organized and would not have rogue vines. I rooted the cuttings and all was well until 4 to 5 years later

when I noticed that the fruit in that part of the vineyard was not like the Pommard from Erath. The clusters

were smaller, ripened earlier, the leaves looked different, and the canes were smaller. One time I asked Jack

where he had obtained the budwood for the cuttings I had bought and he said they had come from Charles

Coury’s vineyard near Forest Grove. Later, I was talking to Mark Teppola who was farming the old Coury

vineyard and asked him about some “Pommard” vines that had small clusters, etc. and were in his vineyard.

He knew what I was talking about but had no idea of the origin of those vines. A friend who managed

vineyards also grew up with Charles Coury’s son, and I talked this over with him. By then, Coury was long out

of the grape business and living in California. Finally, at a Christmas party, my friend asked Charles Coury

where he got the budwood for the “Pommard” with the small clusters, etc.. He confessed that he had

“suitcased” the original budwood from a vineyard in Alsace. It was never Pommard. Since we never found out

more about the origin, we started calling it the ‘Coury clone.’"

It would be helpful to have an easy and inexpensive test to identify Pinot Noir scion(s) accurately. Researcher

Laurent Leduc at Oregon State University received funds from the Erath Foundation to sequence Pinot Noir

clones in Willamette Valley vineyards to determine what the Coury selection(s) actually were. Unfortunately, he

opted to sequence only the scion material easily available to his lab rather that a large selection so his

research did not solve the mystery of the “Coury clone.” In the future, the use of molecular fingerprinting as a

tool to test clonal materials may solve the mystery but the testing is expensive.

In summary, the majority of Willamette Valley Pinot Noir plantings in the 1970s were a combination of

Wädenswil, Pommard, and “Gamay Beaujolais (GB) clones and the Coury selections.The Coury selections

were never planted in California. The Willamette Valley is unique in that Wädenswil is widespread in vineyards

yet there are very plantings of this clone in California.

Many early vineyards were initially planted with a “shotgun” of wine varieties including Gewürztraminer and

Riesling (both are very adaptable to Willamette Valley terroir but neither has gained widespread traction), Pinot

Gris (Oregon’s signature white wine), Pinot Blanc, Chardonnay, Sauvignon Blanc, and even Cabernet

Sauvignon.

Vine spacing in original vineyards was dependent on the size of tractors available at the time and has been

referred to as “John Deere spacing.” Typically, the distance between rows was 10 feet and the distance

between vines was 6-8 feet (10’ x 6’), although the inter-vine spacing tended to be reduced in newer vineyards.

In the early 1970s, many vineyards were planted on a whim without proper viticulture knowledge or experience.

Proper trellising of Pinot Noir was initiated by the Ponzi’s who had studied viticulture in Burgundy. Vertical

trellising was little used in California in the 1970s but the Ponzi’s learned early on that growing the vines

upward in a vertical pattern was preferable for Pinot Noir since the fruit was exposed and not shaded. Charles

Coury has also been credited with moving the VSP trellis system forward.

Collecting verifiable information on the history and current status of Willamette Valley's old vine Pinot Noir

vineyards has been a challenge. That said, many vineyard owners have provided detailed information. My

research indicates that there are currently less than 200 acres of over 40-year-old own-rooted Pinot Noir vines

still in production in the Willamette Valley.

Over the past several months, have reviewed 105 currently available and library old vine bottlings from nearly

every historically significant vineyard detailed in this report. Many of these wines are from the recent

2015-2019 vintages and are still available from the wineries. Almost none of these wines have been reviewed

by any other wine publication.

Why bother with old vine Pinot Noir when so many wines are available from more recent plantings that benefit

from better virus-free scion material, rootstocks and clones, and more sophisticated viticultural technology?

Age is a valuable commodity in vineyards since the aged vine has more potential to reflect the essence of a

vineyard or at least mirror the unique character of the site. Also, there are a number of other generally

accepted observations that support the value of vine age in the quality of the resultant wines. Wine and Spirits

columnist Beppi Crosariol several years ago summed up the superiority of old vine wines. “It’s a difference you

can taste. Old vine wines deliver textural richness and layered flavors that build rather than trail off after the upfront

fruit fades away. It’s analogous to the warm, rich tone of an old violin versus the brighter timbre of new

wood.”

My impressions after tasting many old vine Willamette Valley Pinot Noir wines:

* Less overtly fruity with many non-fruit nuances

* Less grip and better integrated tannins compared to a newer vine wine.

* Almost without exception, the finish is long on the palate and more interesting.

* Invariably balanced.

* Often lighter in color.

* Age extremely well.

* Almost always exceptional although no guarantee of quality.

* Limited, expensive, small production, and often offered only to wine club members since so special.

I am in agreement with wine journalist Joe Czerwinski who said, “

Explanation of confusing terminology in this article:

*In the 1970s, cuttings were typically planted in the ground in a “nursery” either on the vineyard property or

elsewhere. The following year, the now-rooted cuttings were planted in the vineyard proper. Most

winery's date their original plantings to the initial rooting year. Most of the original planting dates in this

article refer to the first planting or rooting of the vines.

*The terms "own-rooted, "self-rooted," and "vinifera-rooted" are interchangeable.

*Many early vineyards were planted to an "upright"selection of Pinot Noir referred to as "Gamay," “Gamay

Beaujolais," or “Gamay Noir" but was most probably UCD 18, a group of FPS selections registered

since 1974 and known as GB type which showed high vigor and an upright growth habit. There were 5

selections in this group that derived from a single vine source on the campus of UC Davis. I use the

term Upright Pinot in this article.