4th International Wine & Heart Health Summit

“The secret to a long life is to stay busy, get plenty of exercise and don’t drink too much.

Then again, don’t drink too little.”

These are the sage words of Hermann Smith-Johannson, a cross-country skier who lived to the ripe age of 103

years. The American public has become obsessed with anti-aging research and claims (note the cover of the

latest issue of Fortune) and yet part of the solution to a long and healthy life has been with us since antiquity.

Physicians have been prescribing wine, as we know from records in ancient Canaan and Cairo, for at least 5000

years. The esteemed physician, Dr. William Osler, was noted to say in the 1800s, “Beverage alcohol is our most

valuable medicinal agent and it is the milk of old age.” And it wasn’t only physicians that knew of the health

benefits of wine. America’s most beloved spokesman, Wills Rogers, once said, “The wine had such ill effects

on Noah’s health that it was all he could do to live 950 years. Just 19 years short of Methuselah. Show me a total

abstainer that ever lived that long.”

The United States is projected to lead the world in volume of wine consumed by year 2010. Appropriate education of the public (and physicians) about regular, moderate, and responsible drinking of wine

could have a very large impact on the health of this country. It is estimated that 71 million Americans

have cardiovascular disease (CVD), or 1 in 3, and CVD is the #1 killer. Cardiovascular disease

touches each of us through our family and friends. A large amount of credible literature has accumulated

in the last 25 years that supports that which educated observers have sensed for a long time,

namely, that wine in moderation is good for heart health.

I recently attended the 4th International Wine and Heart Health Summit

held in Napa Valley, California. This landmark conference, under the

direction of The Desert Heart Foundation in affiliation with the Renaud

Society and the University of New Mexico School of Medicine, presented

to attending doctors, research scientists, food scientists, writers, and

consumers the latest scientific literature on wine and health. The chairman

and the person most responsible for spearheading this biannual

event, is Tedd M. Goldfinger, DO, who heads the Desert Heart Foundation

in Tucson, Arizona.

There is a plethora of research and epidemiologic studies available about alcoholic beverages and

health in addition to the talks presented at this Summit. In this report, I am going to try to sift through

all of this maize of scientific information, and attempt to simplify and summarize the knowledge in a

user-friendly format. I realize that I am preaching to the choir, in that most readers are already wine

enthusiasts who have some belief in the health effects of wine. But perhaps this critical review can

provide further clarity and stimulate the dissemination of this valuable public health information. I

have tried to control my personal biases and look at the data with a critical eye. In addition, I have

attempted to present the facts in layman’s terms whenever possible.

The inconsistencies and conflicting findings and the vagaries of human nature make definitive claims

always difficult in medicine and can, excuse the pun, drive you to drink. Take this humorous piece by

Malcolm Kushner (Vintage Humor for Wine Lovers) which sets the stage for the discussion to follow:

The Japanese eat very little fat and suffer fewer heart attacks than the British or Americans

The French eat a lot of fat and also suffer fewer heart attacks than the British or Americans

The Japanese drink very little red wine and suffer fewer heat attacks than the British or Americans

The Italians drink excessive amounts of red wine and also suffer fewer heart attacks than the

British or Americans

Conclusion: Eat and drink what you like - It’s speaking English that kills you!

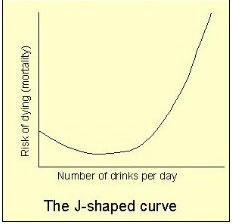

In the 1970s, Arthur Klatsky, M.D., first reported on the benefit of

alcohol consumption in reducing mortality and preventing cardiovascular

disease (CVD). He confirmed the J-shaped curve relationship

between daily alcohol intake and total mortality first described by

Raymond Pearl in 1926. The composite alcohol-total mortality

relationship is a J-shaped curve with the lowest risk among drinkers

who take less than 3 drinks per day. This curve has been validated

by extensive epidemiological studies and holds true for CVD, some

cancers, and cognitive dysfunction as well. Definitions vary, but

light to moderate drinking is considered less than 3 drinks per day

while heavy drinking is 3 or more drinks per day. The definition of a

standard drink varies widely from country to country. In the United

States, a standard drink contains 17.7 ml of ethanol (equivalent to 12

oz of beer, 5 oz of wine, and a shot of 80 proof distilled spirits). In the UK, a standard drink has 10 ml of ethanol. In the United States, a half bottle of wine contains about 2½ to 3½ drinks depending on the

alcohol percentage. To determine the number of drinks in a half bottle, multiple 375 ml by the alcohol

percentage and divide by 17.7. If you drink a half bottle of wine that is 13% alcohol, 375 ml x 0.13 =

48.75 divided by 17.7 = 2.7 drinks. A half bottle of 16% alcohol wine will contain ½ drink more.

If we go back to the early 1990s, alcohol was under attack from many sources including MADD

(Mothers Against Drunk Driving) and prohibitionist groups. The business climate for wine production

was strained by many factors including high interest rates. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) refused

to support any research on alcohol and health. The studies of Klatsky and others were largely

pushed into the background. In 1974, the Framingham Heart Study showed that the risk factors for

CVD were smoking, high blood pressure, increased cholesterol, and abstinence from alcohol. The

NIH, which sponsored the study, was so concerned about the “evils” of drinking, they ordered the

researchers to remove all reference to alcohol in their published report. They advised the researchers

to either provide no comment or state that “It (alcohol) has no effect.” During this time period,

Serge Renaud, PhD, working at the French National Institute for Health, and Curtis Ellison, MD, a professor

at Boston University, proposed to the NIH a cross-cultural epidemiological study on the health

effects of alcohol. The NIH rejected the application and these researchers fortunately had the fortitude

to search elsewhere for their funding.

“When I read about the evils of drinking, I quit reading.” … ...H. Youngman

Morley Safer, a reporter on the popular CBS television program, 60 Minutes, was a

Francophile whose neighbor was the French-born chef, Jacque Pépin. Pépin had told

Safer (right) that the French had a very low rate of CVD and Safer was curious. Safer

consulted with Curtis Ellison, MD, professor and chief of preventive medicine and

epidemiology at Boston University School of Medicine. Ellison told him the French

secret came simply down to wine, food and lifestyle. The French were known to outlive

Americans by about two and a half years and suffer 40% fewer heart attacks even though smoking

was a national pastime, their diet was loaded with saturated fat, and exercise was, well, an afterthought.

The French, however, consumed moderate amounts of red wine regularly with meals, they

ate more fresh fruit and vegetables, they took longer to eat meals and snacked less, they ate less red

meat and more cheese, and used more olive oil and less lard or butter. Of these factors, Ellison said

the link with moderate and regular consumption of wine with meals was the strongest and most scientifically

proven. Frenchman, Serge Renaud, PhD, had studied the relationship between the low rate of

CVD and moderate wine intake in the French population and had confirmed Ellison’s beliefs. Safer

aired the now famous program on the “French Paradox” on November 17, 1991. Safer asked Renaud

on air what the lower mortality for CVD in the French was due to. Renaud answered, “I think it is the

alcohol.” Safer closed the show holding up a glass of red wine and by the next day, red wine mania

had hit the United States. Within weeks of this program, sales of red wine in the United States shot up

40% (about 2.5 million bottles), and Gallo Winery had to put their leading brand, Hearty Burgundy, on

allocation. You might say that America had taken the health message to heart. This was a seminal

event that restored optimism in the wine industry, set the tone for political correctness in describing

alcohol as beneficial, and caught the imagination of the public.

Serge Renaud published his now famous paper in the medical journal, The Lancet : “Wine, alcohol,

platelets, and the French paradox for coronary heart disease.” (S. Renaud and M. De Lorgeril, June 20,

1992, pp 1523-1526). In this paper, he emphasized that “At the moderate intake of alcohol associated

with the prevention of coronary heart disease (CHD), the mechanism of protection seems to be, at

least partly, a hemostatic effect, possibly a decrease in platelet reactivity.” It became soon apparent

to Renaud and others that the explanation of the French paradox was “due to at least partly to a moderate

intake of wine, possibly through polyphenols.”

Serge Renaud, now in his 70’s, is pictured above at the recent Summit. His legacy has been preserved

with the formation of The Renaud Society, a group of medical professionals with an interest in better

health and a passion for wine. At the meeting, the inaugural Renaud Society wine was introduced. It is

a meritage Bordeaux Superieur from the 2003 vintage bottled by The Famille Manein in Bordeaux.

Wine has been shown to have multiple biological effects. Below is a summary of the major categories.

Digestive

Wine is potent against Escheria coli and other bacteria. Interestingly, this has been known back to at

least the time of the Roman Empire, when the armies carried wine with them in their travels to avoid

diarrhea. Wine has been shown to reduce gall bladder disease. An unwelcome effect is that alcohol

will increase gastric reflux and may be troublesome to those with hiatal hernia.

Cardiovascular

Effects are widespread and multiple including antioxidant effects by preventing oxidation of molecules

such as LDL, (the low-density lipoprotein, so-called “bad cholesterol” which in its oxidized state

contributes to atherosclerosis or plaque formation and hardening of arteries); direct effects such as

increasing HDL (high-density lipoprotein, or “good” cholesterol which is anti-inflammatory and reduces

the risk of atherosclerosis; anti-thrombotic or anti-coagulation effect (reduces the “stickiness” of

platelets); and modification of the function of the vascular endothelium (in cell culture red wine inhibits

endothelin or ET1 which causes blood vessel constriction leading to atherosclerosis). The actions of

wine are very complex, and poorly understood at this time. The lay press has referred to the ability of

polyphenols in wine to “mop up free radicals,” as an explanation for their cardiovascular benefit, but

certainly this public explanation is an over-simplification. Recent research indicates that specific

effects on inflammatory processes are more important than antioxidant effects. Moderate drinkers may

show a mild increase in blood pressure which is thought to have no clinical importance. Those with

hypertension should not be discouraged from drinking moderately as long as they are on treatment

for their high blood pressure. Studies have shown that the low to moderate intake of wine significantly

reduces not only CVD and CHD, but also cerebrovascular accidents or stroke (CVA), congestive heart

failure (CHF), high blood pressure, and peripheral vascular disease.

Metabolic

There is a 30% reduction in risk of developing diabetes mellitus with moderate wine consumption. In

addition, diabetics who imbibe regularly and moderately have a decreased risk of dying from cardiovascular

disease. There is a decreased rate of osteoporosis and multiple sclerosis in wine drinkers.

Cancer

There is an increased incidence of esophageal and breast cancer with high consumption of alcohol

(more than 8 drinks a day in an Italian study). Women are faced with a dilemma in that there is about

a 10% increase in breast cancer but a 50% reduction in CVD with light to moderate wine intake. If

middle aged and older women have adequate folate in their diet and are not on hormone replacement

therapy, the incidence of breast cancer in low to moderate drinkers of wine is the same as abstainers.

Wine seems to decrease the risk of colorectal cancer, dramatically reduce the risk of gastric cancer,

and decrease the incidence of kidney cancer, prostate cancer, and lymphoma. The beneficial mechanisms

are complex, but it would seem that polyphenols in wine inhibit cellular events associated with

tumor initiation, promotion, and progression. One polyphenol, resveratrol, may have also have therapeutic

value in cancers. In animal studies, it promotes the death of cancer cells by inhibiting a gene,

NF kappa B, which is released by the body’s immune system to protect cells, including cancer cells,

from chemical and radiation attack.

Mental Performance

Wine seems to preserve cognitive function in aging individuals. There is a significant decreased risk

of Alzheimer’s disease and dementia in low to moderate wine drinkers. Wine buyers tend to purchase

and eat healthier food compared to people that buy beer. Also, there is an increasing IQ with increased

preference for wine over other alcoholic beverages.

Weight Change

There are lower rates of obesity among drinkers and decreased weight gain overall. Although a drink

of wine provides approximately 100 calories, wine is metabolized differently from other caloric intake.

The French, who have a very low rate of obesity, are a perfect example of this observed effect.

The observed favorable consequences of regular and moderate wine intake are thought to be secondary

to the combined effects of alcohol and multiple polyphenols. Acting together, they influence

vascular, hemostatic, and inflammatory functions that combine to produce cardioprotection, reduction

in carcinogenesis, improved cognitive function, and a number of favorable metabolic changes.

Much of the research on wine and health has centered on the polyphenols. These are chemical

substances known as phytoalexins or phytochemicals, compounds derived from plants that have

biological activity in the human body. In wine they include the flavonoids (resveratrol, quercetin,

catechin, anthocyanin and procyanidin), tannins, and sulfides. The polyphenols are not unique to

wine, and occur in abundance in many foods such as raspberries, blueberries, pomegranates,

peanuts, green tea, extra virgin olive oil, and other plants. There are more polyphenols in wine than in

grape juice because the fermentation process extracts more of these phytochemicals. One glass of

red wine has 200 mg of phenolic compounds compared to 40 mg for white wine. There has been some

interest of late in wines from specific regions, which by virtue of their vineyard locations and respective

winemaking techniques, have particularly high levels of polyphenols such as resveratrol. For example,

resveratrol levels are increased in red wines from Argentina where the vineyards are at high

altitude. Presumably, the elevated concentration of polyphenols in the grapes develop as a protective

response to the intense ultraviolet light at the increased altitudes. These wines have been shown in

animals to be potent inhibitors of ET1 and the press has been quick to anoint these wines as

“healthier.” A crazy idea, of course, because everyone knows Domaine de la Romanee-Conti Le

Tache is the healthiest wine (just kidding). The fact is, and this was emphasized at the meeting I attended,

only small amounts of polyphenols are required to produce their beneficial health effects.

There is absolutely no evidence to indicate that a special polyphenol-endowed wine is healthier in humans.

Don’t fall for the press hype. The crux of the matter is that light to moderate drinking of red

wine is beneficial, regardless of the red wine that is imbibed.

Resveratrol is the polyphenol “most likely to succeed” if you were to believe the press. There were at

least 600 scientific studies in the literature in 2006 that mentioned resveratrol. Resveratrol has been

shown to increase the life span of yeast cells, round worms, fruit flies, and short-lived fish. Research

reported last November caused quite a stir in the press. A research team reported that mice fed high

doses of resveratrol could be kept from gaining weight, despite being kept on a high fat diet. In addition,

their aging process was slowed and their running stamina was improved. David Sinclair has been

involved in a number of resveratrol studies and has partnered with CEO Christophe Westphal to form

Sirtrus Pharmaceuticals to develop medications that have the same effect as resveratrol does on mice.

In the Fortune article pictured on page 1 of this report, it is reported that the co-founders have raised

$82 million over the past 2 years to fund their research. They have already developed a resveratrollike

drug (501) that helps people with diabetes mellitus keep their blood sugar controlled. The drug

delivers a large amount of resveratrol to the blood stream, in theory activating SIRT1 (the origin of the

name Sirtrus for the company) which is an enzyme in cells that stimulates the formation of new, healthier

mitochondria that do not throw off damaging radicals like their aging brethren. The result is a boost

in the metabolic rate. At this point in time, it is not clear whether their research will be successful, as

many scientists believe resveratrol has complex actions on many different molecules, and may need

alcohol and other polyphenols to exert its full effects. The author of the article in Fortune, David Stipp,

advises readers to “Pour a glass of Pinot Noir, and while imbibing, step back and regard the big picture.

The dream (of extending life span) is likely to be realized within, at most, a few decades.”

25 facts to hang your stem on:

1. The mortality rate from CHD is lowest in Japan, second lowest

in France.

2. Moderate drinkers of any type of alcohol have less CHD

compared to abstainers (see graph).

3. The benefits of alcohol consumption last approximately 24

hours, so alcohol should be consumed regularly, even daily.

4. Binge drinking (3 drinks in less than 2 hours) negates the

effects. The most benefit is gained from small amounts of alcohol drunk regularly.

5. Moderate drinking has little effect on cardiovascular medications (coumadin, blood pressure,

hypoglycemic medications), in contradiction to warnings to the contrary.

6. There is a lower risk of death in light to moderate drinkers of any type of alcoholic beverage. This

is true for both sexes, and all races.

7. Heavy drinking increases the risk of gastrointestinal cancers, cirrhosis, and breast cancer.

8. The leading cause of death in women is heart disease, not breast cancer as is often believed. More

women die from CVD than cancer at any age.

9. In women, moderate alcohol drinking reduces CVD by 50%.

10. More is better is a fallacy. Research indicates there are enough polyphenols in most any red wine

to produce beneficial physiological effects.

11. Intelligent drinking should be encouraged in middle-aged and older adults as long as there is no

contraindication. It seems that people can drink more as they get older with no harmful effects.

12. Drunkenness is unacceptable behavior and leads to adverse social and health consequences.

13. Resveratrol is the most publicized polyphenol in red wine, but there are many polyphenols that act

synergistically to produce beneficial health effects.

14. Health-improving behaviors are critical to well-being. There are 5 healthy lifestyle factors that are

important in preventing CVD and diabetes mellitus: (1) avoid smoking, (2) stay lean, (3) exercise

regularly (at least 30 minutes a day), (4) follow a diet low in animal fat, high in fiber, and (5) intake

of ½ to 2 drinks of alcohol per day. A 2006 study showed that there is a 70% decreased risk of CVD

if #1-4 are followed, and #5 is then added to the other 4.

15. A small amount of fat is healthy. Mortality increases if a person is too thin. However, obesity is

unhealthy and currently a major health problem. The population in every state of the United States

is now 20-25% obese.

16. Intervention studies in animals show that wine and/or polyphenols from wine show a definite

advantage over the administration of ethanol by itself.

17. Dietary supplements containing high amounts of polyphenols such as resveratrol have no proven

health benefit. Why take a pill when the benefit is perfectly packaged naturally in wine?

18. Danish studies show beverage specific differences with wine drinkers having health advantages

over beer and distilled spirits drinkers. Wine drinkers have a lower cancer risk and less abdominal

obesity than beer or distilled spirits drinkers. In Denmark, moderate consumption of wine

reduces the risk of CHD and CVA by 60%.

19. Breaking research as yet unpublished from Dominique Petithary-Lanzmann, M.D., PhD (who has

worked with Serge Renaud for 20 years) involves a prospective study of 42,883 French men from

eastern France. Many confounding variables were adjusted. The results showed that moderate

wine drinkers compared with abstainers had a lower risk of death from all causes and moderate

beer drinkers compared with abstainers had no decrease of risk.

20. Wine drinkers have lower mortality at all levels of blood pressure.

21. Research (Francois M. Booyse, PhD, University of Alabama Birmingham) has shown that levels of

alcohol and wine polyphenols associated with moderate consumption will be expected to increase

endothelial cell mediated fibrinolysis to promote and sustain increased blood clot lyses in humans.

CVD protection will then be achieved, in part, by the ability of increased fibrinolysis to reduce the

risk for early thrombosis and later acute CHD-related atherothrombotic consequences of myocardial

infarction (heart attack) and hence overall CHD-related mortality. The point is, make sure you

have been drinking red wine at least two weeks before your heart attack.

22. Under-reporting of intake (for example, heavy drinkers reporting lighter intake) lowers the threshold

for apparent harm, and reduces the apparent magnitude of benefit from light to moderate

drinking.

23. One of the problems of alcohol research is that there are no randomized controlled trials. Some

critics have attributed the findings to the “healthy drinker hypothesis,” that is, attributing the results

to the drinker, not the drink. Light to moderate drinkers might be healthier (exercise more,

eat a healthier diet). A 2006 study refutes this hypothesis. When studies are full-controlled for

confounders, there is still a benefit for light to moderate drinking and the findings confirm the Jshaped

curve.

24. Arthur Klatsky will soon publish his latest data validating the J-shaped curve. The benefit of light to

moderate drinking dips below the line and stays until 3-5 drinks a day. The curves for men and

women are similar, with women having a slightly increased benefit of light to moderate drinking

compared to men. There are no ethnic differences in the effect.

25. Educating the public makes an impression: many measures of alcohol abuse have been reduced

in the United States in recent years.