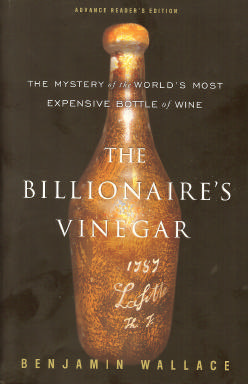

The Billionaire’s Vinegar

I just finished reading Billionaire’s Vinegar, The Mystery of the World’s Most Expensive Bottle of Wine by

Benjamin Wallace (Crown Publishers, Random House, NY, 2008, $24.95. paperback), and just as if I

had quickly polished off a glass of great wine, I wanted more. My developing passion for wine during

the 80’s and 90’s coincided with the events that transpired in this story, so it was not surprising that I

was enthralled by the intrigue of this tale of greed, deception and excess.

The story centers on a bottle of 1787 Chateau Lafite, reputedly

owned by Thomas Jefferson, which was consigned to

Christie’s Auction House.. The bottle, engraved with the initials,

Th. J., was scheduled to be auctioned on December 5,

1985 by Christie’s Wine Director, Michael Broadbent, the

“public face” of wine auctions of the time. The consignor was

a supposedly German-born wine collector Hardy Rodenstock,

whose real name, Meinhard Görke, and country of

birth, Poland, only become public years later after a former

FBI investigator uncovered the truth. Rodenstock, who had a

penchant for uncovering extremely rare bottles of wine, said

that he obtained a cache of Jefferson bottles in the spring of

1985 from a hidden cellar in Paris discovered after workers

tore down a house and broke through a false wall in the basement.

Rodenstock claimed that he had paid $2,227 for the

stash of bottles, but the exact number was never determined

or spelled out by him.

Thomas Jefferson, the third President of the United States, had

lived in Paris from 1784 to 1789 where he served as Commissioner

and them Minister to France. Jefferson was an exceptional

wine connoisseur of his time and frequently purchased

fine French wine. Despite this, none of his bottles had ever

previously been found. The bottle of 1787 Chateau Lafite was be the oldest “authenticated” vintage

red wine ever to come up for auction at the time. Christopher “Kip” Forbes, son of billionaire publisher

Malcolm Forbes, was sent by Malcolm to buy the bottle at the auction. Malcolm had an extensive

cellar of first-growth Bordeaux wines and even boasted of “popping open a Margaux to drink with

a Big Mac and fries”. Forbes paid $156,000 for the reputed Jefferson bottle, a new record for a bottle

of wine and the event was memorialized in the Guiness Book of World Records.

This auction brought considerable notoriety to Christie’s and Michael Broadbent and fueled the frenzy

for rare wines which had begun in 1967 when Christie’s held its first “Finest and Rarest Wines” sale.

By 1985 when the Jefferson bottle was auctioned, much of the world’s old clarets had been discovered,

sold and drank. It was not surprising then that counterfeiting of impossibly rare wines was becoming

commonplace, leading to the premise of this book: Could the Jefferson bottle be fake as well?

Solving this mystery turns out to involve all of the major wine figures in the world over the last fifty

years: Marvin Shanken, owner and publisher of The Wine Spectator; William Koch, a billionaire who

amassed a prodigious cellar of 35,000 bottles, and purchased several supposed Jefferson bottles; Lucia

(Cinder) Goodwin, a Jefferson scholar at Monticello; Marvin Overton III, a Texas neurosurgeon who

amassed a 10,000 bottle cellar; Lloyd Flatt, a Tennessean wine collector with 30,000 bottles; Tawfiq

Khoury, who possessed the largest wine collection in America at the time - 65,000 bottles; Bill Sokolin,

owner of the wine store, D. Sokolin & Co.; Georg Reidel, a friend of Rodenstock’s; Jancis Robinson, one of the world’s most respected wine critics; Robert Parker, Jr., publisher of the Wine Advocate;

Comte Alexandre de Lur Saluces, proprietor of Chateau d’Yquem; Bipin Desai, an American collector

who staged grand tastings of old and rare wine; Dennis Foley, the auctioneer at Butterfield and

Butterfield in San Francisco; John Tilson, publisher of Rarieties; Yeter Göksu, a physicist who dated

wine sediment using thermoluminescence; Manfored Wolf, a chemist who developed techniques for

dating wine using a method for detecting the radioactive isotope tritium; James Laube, columnist for

The Wine Spectator; Lord Jacob Rothschild, part of the first family of Bordeaux; Hugh Johnson, an English

wine writer; Serene Sutcliffe, Wine Director of Sotheby’s and Broadbent’s arch rival; Angelo Gaja,

an prominent Italian winemaker; Steve Verlin, an East Coast wine collector and one of the founders of

Veritas restaurant in New York; Denis Durantou, proprietor of Chateau l’Englise Clinet; David Molyneux-

Berry, a one-time Wine Director at Sotheby’s; and Jim Elroy, a former FBI agent that Bill Koch

hired to root out the provenance of the Jefferson bottles. This list is by no means complete and many

other wine fanciers are drawn into this drama.

In detailing the mystery of the Jefferson bottles, the author reveals the fascinating history of several

trends in the world of fine wine collecting which were in some way impacted by, or intertwined with,

the 1985 auction of the first Jefferson bottle. These include the history of the Bordeaux wine trade, the

success of the large wine auction houses, the rise in popularity of mega-tastings of old wine, the new

interest in the pairing of food and wine, the emergence of tasting notes, the vertical increase in prices

of luxury wine labels, the development of technology for dating old bottles of rare wine and for anticounterfeiting

new releases of wine, and the historically changing center of the fine wine market which

began in the UK, crossed the ocean to the United States, and most recently became centered in Asia

and Russia.

Counterfeiters have seen wine as an easy take and the rare wine pool is forever

suspect. As Robert Parker, Jr. noted, “This is the only product in the

world that you can sell for thousands of dollars without a certificate of origin.”

Just this last week, Peter Hellman reported in Wine Spectator online that

twenty-two lots of Domaine Ponsot Clos de la Roche and Clos St.-Denis Burgundies,

worth as much as $603,000, had to be withdrawn from the April 25,

2008 Acker Merrall & Condit’s wine auction. Laurent Ponsot, the fourthgeneration

owner of Domaine Ponsot, said the wines were fakes and some

were from vintages that the domaine never bottled. William Koch, whose lawsuit

against Hardy Rodenstock is detailed in The Billionaire’s Vinegar, filed a

lawsuit against Acker Merrall & Condit two days before the auction. Koch

claimed that he was sold counterfeit rare wines in 2005 and 2006. John Kapon,

the owner of Acker Merrall & Condit is disillusioned as are many others and

admits that “we might have to slow down and tighten up to ensure that some of

these old treasures are what they’re supposed to be. Hellman notes that at Christie’s, any lot of wine

valued at $20,000 or more must be subjected to multiple inspections by experts. It might be too little,

too late. as the problem of counterfeit wines threatens the validity of multiple old tasting notes published

in the world’s wine literature over the last fifty years, not to mention the large and possibly

fraudulent monetary losses already suffered by a number of billionaires.