Willamette Valley Appellations

Oregon is known as the Beaver State, but it would be more apropos to label it the Pinot Noir State. I would

even suggest that the Oregonians go one step further and name their state Noiregon. This is not a stretch,

since Oregonians have a Pinot fixation that consumes them. Pinot Noir is by far the most widely planted grape

in Oregon, totaling 9,858 acres out of a total of 17,400 acres (2007 data), second only to California in the

United States. Pinot Noir accounts for 50% of total case sales, most of it crafted by small family owned

producers who dot the rural landscape of the Willamette Valley.

There has been an impression that Oregon’s winemaking community is primarily ex-hippies making Pinot Noir

out of garages in their backyards. That might have had some validity back in the 1970s, but nothing could be

further from the truth now. The newest generation of winemakers represent highly educated and talented

masters of their craft working out of state-of-the-art wineries. By any measuring stick you choose, Oregon Pinot

Noir is world-class. Perhaps the greatest vindication of the quality of Oregon Pinot Noir has come from the

Burgundians who eagerly attend the yearly International Pinot Noir Celebration in McMinnville, Oregon, and the

Steamboat Conference in southern Oregon which precedes it. Domaine Drouhin Oregon was Burgundy’s first

committed interest in Oregon, but more are following, including respected vigneron Dominique Lafon, who

became a consulting winemaker for Evening Land Vineyards this year.

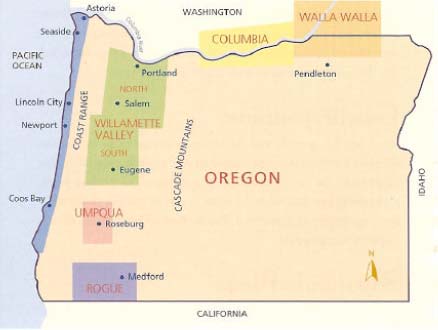

There are five major wine growing regions or appellations in Oregon. Oregon and Washington share the

northern Columbia Gorge and Walla Walla appellations. The three western Oregon appellations are the

Willamette Valley, the Umpqua Valley, and the most southerly Rogue/Applegate appellation. Some Pinot Noir

is grown in selected microclimates in the Columbia Gorge, Umpqua Valley and Rogue appellations and show

promising potential, but the Willamette Valley is Oregon’s heartland for Pinot Noir.

The Willamette Valley, so named for the river that runs through it, is 150 miles in length and 60 miles wide,

extending over 3,438,000 acres from the Columbia River in Portland south through Salem to the Calapooya

Mountains outside Eugene. The central Willamette Valley is situated at 45 degrees north latitude, the same as

France’s Burgundy region. The Willamette Valley accounts for 75 percent of the total acreage and wine

production in Oregon and is divided into a north and south portion, with the border located just below the

state’s capital of Salem.

The Willamette Valley is home to most of the over 370 wineries in Oregon and is ideal for growing Pinot Noir,

with cool winters and warm, dry summers. Rain occurs almost entirely in the winter. There are more daylight

hours during the growing season than any other region in the state. Most vineyards are on hillsides, from 200

to 800 feet above sea level, south or east facing, and situated west of the Willamette River. The hillside soils

are ideal for growing grapes and consist of three types: basaltic soils which are composed of extrusive volcanic

rock that is fine-grained and grey in color with loam and silt stained red by iron oxide (termed Jory soils);

sedimentary soils formed by erosion of distant land masses and transported by water that are yellow to brown

in color, typically loam over siltstone (termed Willakenzie soils); and loess soils which are deposits of silt laid

down by wind action, fine-grained and light brown in color. Think fire, ocean and wind. Soil terminology can be

very confusing. For the geology challenged, loam is soil composed of sand, silt and clay; silt is soil or rock of a

grain size between sand and clay. The Oregonians have a singular obsession with soils and they will talk

about it on end. It is part of their Pinot fixation. For the full story on the geologic history of the Willamette

Valley, visit the Bethel Heights Vineyard website (www.bethelheights.com) and read the excerpt from Oregon

Pinot Camp 2008 titled “Soil into Wine.”

The deep alluvial soils (soil or sediment deposited by river water) on the valley floor possess high water holding

capacity and are not conducive to grape growing. In addition, the threat of frost is always present at lower

elevations, and some of the earliest attempts to grow grapes in Oregon failed because the vineyards were

planted on the valley floor.

The different soils contribute disparate flavors to the grapes grown in them. THIS IS THE KEY LESSON IN

THIS ARTICLE! Willakenzie soil imparts more dark fruits, earthiness, chocolate, anise and spice with more

structured tannins. Jory soil, in contrast, tends to produce wines that are redder fruited with sassafras,

pomegranate and baking spices with good acidity and softer textures. These flavor profile generalizations are

frequently difficult to clearly discover in Oregon Pinot Noir because of the many other variables involved such

as vine age, clonal and rootstock material, vintage variation, and the winemaker’s hand. The winemaker in

particular can play a significant role, challenging the taster to identify “land or hand?” Specific flavor profiles of

the different appellations are often identifiable by the winemaker’s trained palate, but are considerably more

challenging for the consumer to recognize.

Within the large Willamette Valley appellation, which was approved in 1983, there are six smaller appellations

located in the northern valley, each of which have distinctive microclimates, geography and soils. The six

include Chehalem Mountains, Dundee Hills, Eola-Amity Hills, McMinnville, Ribbon Ridge, and Yamhill-Carlton

District. The sub-appellations of the Willamette Valley were conceived primarily by California ex-patriot

winegrowers who felt the Willamette Valley would benefit from an appellation system already successfully in

place in California, by bringing more visible identity to the specific sub-regions of the Willamette Valley. Initially,

several winegrowers in the valley did not receive the idea warmly, fearing that this scheme would fragment the

region and dilute the prestigious Willamette Valley image. For the most part, this has not been the case. The

locals admit that there is still a tremendous amount of information to be gathered and realize that it will take

years to arrive at a definitive picture of each appellation. Winemaker Jesse Lange reflects the current opinion

of many saying, “I believe whole heartedly that the AVA system for Oregon has just begun to blossom and will

become more entrenched and respected as the vintages accrue. That’s where most of the fun is, aye?” The

main underlying goal is to demonstrate differences among the appellations, without implying one appellation is

superior to another. A topographical map of the Willamette Valley appellation and its six sub-appellations is on

page 3 (courtesy of the Oregon Wine Board). Note the location of the Van Duzer corridor as this will be

referenced several times in the following pages, particularly regarding the Eola-Amity Hills appellation.

In the following pages, I have profiled each of the six Willamette Valley sub-appellations based on my review of appellation applications to the TTB and discussion with numerous winemakers in the Willamette Valley. In

addition, extensive tasting notes gained during my recent visit to the Willamette Valley are provided from each

sub-appellation. Finally, a Willamette Valley sub-appellation tasting with the Grape Radio gang will be

presented. This will also be available in podcast format soon at www.graperadio.com.