12th Annual World of Pinot Noir

Each year on the first weekend in March a few thousand pinot geeks converge on the small beach side

community of Shell Beach at The Cliffs Resort to revel in the wines made from their favorite grape. This year’s

event was exceptional thanks to the efforts of Karen Steinwachs, the 2012 Chairperson, and the dedicated

work by the World of Pinot Noir Board of Directors and Advisory Committee. It was a weekend to renew old

friendships and make new friends, to discover new Pinot Noir producers as well as revisit established Pinot

Noir vintners, and to taste the current bounty of Pinot Noir from North America, New Zealand, Australia, Chile,

and Burgundy.

Two seminars were offered on Friday, March 2, hosted by winemaker Fintan Du Fresne and the crew at

Chamisal Vineyards in Edna Valley. The first seminar, titled “Technique v. Terroir: The Cube Project,” was

moderated by yours truly, and the second seminar, “Natural Winemaking,” was moderated by noted Pinot Noir

expert, John Haeger. I will summarize the discussion and conclusions reached at each seminar.

Technique v. Terroir: The Cube Project

Three winemakers, Thomas Houseman of Anne Amie Vineyards in Carlton, Oregon, Andrew Brooks of

Bouchaine Vineyards in Napa Carneros, California, and Leslie Mead Renaud of Lincourt Vineyards in Santa

Barbara County, California, met at the Steamboat Conference for winemakers held in Oregon each year before

the International Pinot Noir Celebration. They decided to devise an experiment in terroir that involved the three

winemakers and their three vineyards, with 9 wines resulting from three vintages (thus the “Cube” designation).

The three wineries picked 6 tons from a block of Pommard clone Pinot Noir, dividing it into thirds, with each

winemaker fermenting 2 tons of fruit. Each winemaker was responsible for picking decisions at their own

winery and the grapes were picked on the same day. In this way, each of the three wines made from that

particular lot started on equal footing. Each individual winemaker crafted the wine from the two other vineyards

in the same fashion as the wine from their own vineyard. The regimen would be repeated for three vintages,

2010, 2011 and 2012.

The details

The Cube Project is about community, terroir and creative expression of the winemaker. It is a unique

opportunity for each winemaker to see their home vineyard through another winemaker’s eyes. It also offers

the opportunity to compare wines from the same terroir made by different winemakers to see if the stamp of

terroir shows through, and to compare three wines from different sources made by the same winemaker to see

if the winemaker’s signature is evident in the wines. The experiment also offered the opportunity to study the

different stylistic imprint of the Pommard clone from three diverse regions.

The winemakers had tasted the wines when very young (July 2011) in a blind and randomized fashion. The

consensus was that the stamp of the winemakers and the vineyards was very clear. The overwhelming

consensus of the seminar attendees (over 100 people) was that at this stage in the wines’ evolution, the

signature of the winemaker was much more evident than the terroir. One would expect that winemakers would

be more adept at making the distinction between winemaking and terroir, but there were a number of

winemakers in the audience as well.

It has been a frequent refrain among wine critics that many of the Pinot Noirs crafted today reflect the interest

of the winemaker more than the uniqueness of the vineyard. In this regard, the question was posed to the

winemakers at the seminar whether it is more important for a wine to reflect its place of origin or taste good. It

is a common conundrum for winemakers and this question resulted in quite a bit of discussion. It seemed that

the winemaker panel felt that taste takes precedence over place of origin. The fact that many consumers in the

seminar audience could not clearly distinguish terroir in the wines from a single source made by three different

winemakers would seem to reinforce the overriding importance of the flavor of the wine over terroir, particularly

from a commercial success viewpoint. As Charlie Oiken has pointed out (Connoisseur’s Guide to California

Wine), “I hope that winemakers and wine lovers do not fall into the trap of blindly believing that those Pinots

that identify a particular plot are inherently superior to those that do not. Place is important, but so is the

winemaker’s craft.”

What is Terroir?

There are a number of definitions of the word terroir, a French term that has no equivalent in the English

language. The term dates to 1300-1500 AD, originating in Burgundy where vignerons believed so

strongly in the importance of soil and climate that they coined the word terroir. Today, Anthony Hanson

MW (Burgundy) points out, “In Burgundy, they love the word terroir and have virtually turned it into a

religion.”

The briefest one word definition: “soil.”

The three word definition: “It's the place.”

The American definition (John Haeger, North American Pinot Noir): “Terroir encompasses all the physical

properties of a site including the mesoclimate, orientation and aspect.”

The official French definition (from a committee that included winemaker Michael Chapoutier): “Terroir is

the sum of the soils, climates and humans.” It is the blend of geology and the health of the soil,

the microclimate where the vines grow and each year's vintage condition along with winemaking

talent and knowledge.”

The French definition of terroir includes the winemaker and winegrower. Jamie Goode and Sam Harrop

(Authentic Wine) concur: “The human element of terroir is important. Human input shapes the must and

the wine in so many ways excluding it from the definition of terroir is ludicrous.” Others believe that

terroir can only encompass natural occurring elements, the work of God so to speak.

The Cube Project wines will be available for sale. The 2010 vintage wines will be released in the Fall of 2012.

Ordering details are below.

Natural Winemaking

The panelists for the Natural Winemaking seminar included both small winery winemakers who practice

various degrees of “natural” winemaking (Bradley Brown, Big Basin Vineyards; Peter Cargasacchi,

Cargasacchi Vineyards; Nathan Kandler, Thomas Fogarty Winery; and Joe Wright, Left Coast Cellars), larger

wineries that do not pursue the extremes of “natural” winemaking due to economy of volume concerns (Scott

Kelley, Estancia Estates Winery; Brian Maloney, DeLoach Vineyards), a well known author and proponent of

“natural” wines (Alice Feiring, Naked Wine), and the founder of Vinovation (a provider of alcohol reduction

tools, volatile acidity reduction, juice concentration, supplier of tannin adjunct, etc) and vintner at WineSmith,

Clark Smith.

Moderator John Haeger opened the discussion by pointing out that there is no specific definition of “natural”

winemaking or “natural” wines. Natural winemaking would seem to be what many winemakers claim they do,

that is, “I am completely hands off, non interventional and let the wines make themselves,” but in reality do not.

As winemaker Ted Lemon points out in the excellent book, Authentic Wine, “The term natural winemaking is an

oxymoron. Consumable wine does not occur in nature. At Littorai we prefer the older description minimal intervention

winemaking. The goal, however, is the same: to intervene in the fermentation and aging process

as little as possible and always to favor simple physical inputs (temperature and humidity control, moving wine

by gravity flow whenever possible) rather than chemical ones.”

In general, natural winemaking involves natural winegrowing (no irrigation, organic pesticides and herbicides, if

any, etc.), indigenous primary and secondary fermentations, the use of very little or no sulfur dioxide throughout

the winemaking and bottling process, the absence of additions of any kind such as enzymes, and no fining or

filtration. Proponents of natural winemaking believe that the wines that result are the purest expression of

place.

John Haeger surveyed a significant number of winemakers about their use of various winemaking techniques,

comparing those who called themselves natural winemakers as opposed to those admitted interventional

winemakers. His survey found that 60% of the winemakers claim to divulge everything about their winemaking

technique (a high figure Haeger believes), and 40% are selective about what they admit regarding their

winemaking technique.

Questioning winemakers about their practice of inoculation in both primary fermentation and malolactic

fermentation indicated there was a significant difference, with natural winemakers more frequently refraining

from inoculating fermentations (arrows indicate significant difference).

When surveyed about additions during winemaking, a significant number of natural winemakers never use

enzymes compared to interventional winemakers.

A significant difference was noted when winemakers were asked about fining with natural winemakers reporting

that they rarely did it. There was no significant difference among winemakers of both types as to the use of

filtration.

A significant difference was found in the use of sulfur dioxide at the crusher with natural winemakers most often

using little or none.

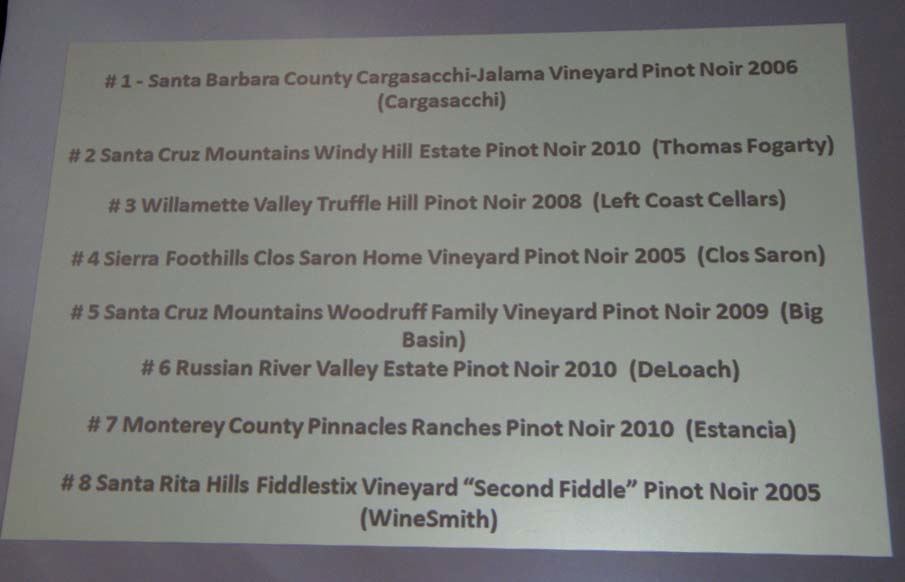

The wines presented for tasting:

The #4 wine from Clos Saron is the most true to the “natural” winemaking paradigm and was the single

problematic wine at the tasting. The Clos Saron Pinot Noir has no detectable sulfur dioxide at bottling. There

was variation in the bottles of Clos Saron Pinot Noir poured at the event and this is the rub against natural

wines. The sample I tasted and those samples poured from the same bottle and tasted by others in my vicinity,

showed considerable funky aromas, with clear evidence of oxidation. The wine seemed way beyond its year of

harvest in maturity. Sulfur dioxide, of course, acts as a antimicrobial and antioxidant and is usually added in

small amounts at the time of bottling. Without this addition, there is a risk of a flawed and commercially

unacceptable wine such as the bottle poured for this seminar. I have had a number of Clos Saron Pinot Noirs

over the years and they have been generally pristine, but like the bottle poured at this seminar (and another I

tasted at Pinot Days a few years back), they can be subject to microbial and oxidative irregularities.

The #7 wine from Estancia Estates was made from machine-harvested grapes, using extensive interventional

winemaking techniques to produce 250,000 cases, yet it was a very decent, fruity Pinot Noir. Winemaker Scott

Kelley pointed out that the larger the production, the more economic risk involved, and the resultant necessity

for the winemaker to intervene at multiple stages of the winemaking process to insure the large volume of wine

is sound for commercial release.

The #8 Pinot Noir was an experimental wine for Clark Smith, picked at a very low Brix. Smith presented a

lengthy prepared sermon about this wine and the Natural Wine Movement. “I wanted to show that less

hangtime than is customary could produce a deeper, truer expression of the hibiscus blossom and saddle

leather which characterize Fiddlestix. Three weeks before harvest we used an ultrafiltration technique on Pinot

Noir heavy press wine from a sparkling wine producer to create a Pinot Noir cofactor concentrate, neutral in

flavor and without astringency, which was added during fermentation at 1%, resulting in an enhanced extraction

of the cinnamic acid ‘spicy Burgundian flavors’ of clone 667 and of the cherry notes and color characteristic of

clone 115 on this site, greatly enhancing the wine’s terroir expression while maintaining its silky, ethereal style.

Despite its feminine delicacy, the wine’s structural integrity caused it to be quite closed in youth. I regard it as

an artistic triumph and a commercial disaster.” (I agree, the wine was noticeably tannic with considerable

grassy, herbal and floral aromas and flavors unappealing to my palate) His final comment was perplexing in

light of the wine he presented which was clearly unbalanced. “My goals are soulful terroir expression,

balanced presentation and graceful longevity. If the Natural Wine Movement is requesting wines which have

made themselves, they have yet to demonstrate that they will support through purchase the clumsy,

unbalanced wines that often result.”

If you have any interest in the Natural Winemaking Movement, I highly recommend you read the very

educational book, Authentic Wine, by Jamie Goode and Sam Harrop MW (University of California Press, 2011,

hardcover, 259 pp, $29.95 list). With chapters on terroir, biodynamics and organics, chemical and physical

winemaking intervention, and the Natural Wine Movement, the authors cover the complex subject of authentic

wines in relevant detail with sound scientific explanations. There is considerable winemaking information as

well that will serve any wine enthusiast well.

The two seminars were recorded in their entirety by Grape Radio (www.graperadio.com) and will be posted for

listening at a future date.